2019 may be the best time to IPO

Growth matters, profits don’t

Nearly 7,000 scooters appeared to be active in Los Angeles County in January, having logged a ride in the previous two weeks. By April, more than 5,500 of those same scooters appeared to be removed from active duty, with no rides logged for the prior two weeks.

–LA Times on Bird, 5 May 2019

My first thought when I read this article on the scooter company Bird was that now would be a perfect time for it to schedule an IPO. Perhaps it waited too long. It seems like every cash-burning unicorn company is preparing for IPO now, so primed are investors for growth opportunities.

Does it matter that the dockless rental concept has run into the kind of snafus that chased the Chinese dockless bike company Mobike out of Manchester, England? I say no. Right now, revenue growth is what matters for these IPO companies. And these companies should IPO now while they can because these conditions won’t last forever.

WeWork: ‘Borrowing short and lending long’

Take WeWork, for example. It’s joining the IPO crowd. And its last funding round valued the company at $47 billion. And Reuters noted the following about it when it announced:

The company has faced questions about the sustainability of its business model, which is based on short-term revenue agreements and long-term loan liabilities.

That’s sort of like banks running aground in the Great Financial Crisis due to over-reliance on low-cost short-term funding instead of on deposits. When the market conditions changed, these companies ran aground. British Bank Northern Rock failed for this very reason. And all of the big US investment banks were vulnerable. They were bailed out by the Fed.

The same will happen to WeWork when the economy turns down, as their short-term contracts are canceled en masse. Let’s see how the company’s finances hold up. Personally, I expect WeWork to go to zero. This is one company on which I am definitely bearish.

Doesn’t matter. WeWork is growing revenue like gangbusters. And back in 2017, that growth gave them a gigantic revenue valuation multiple. Here’s NYU Professor Scott Galloway:

WeWork is arguably most overvalued company in the world. WeWork is now getting a valuation equivalent of $550,000 per customer. So it’s hard to imagine how they can monetize consumers to the extent that warrants a $550,000 evaluation per consumer. In some instances WeWork, if you do the math, the floor that the WeWork building leases in a building is worth more than the building hosting the WeWork.

I bet if you look at a Regus or another co-working space you’d find that they’re worth kind of single-digit thousands. WeWork makes absolutely no sense that is the perfect example of kind of this frothy market of consensual hallucination between the company and its investors.

They were only valued at $20 billion at that time. WeWork’s value has more than doubled since then. And they’re ready to cash in.

No Growth? Expect value to collapse

Blue Apron shows you what happens when growth stalls. It IPO’ed at a valuation of $1.9 billion in 2017. At the time, it had just finished the past year doubling revenue to $795.4 million last year. The net loss of $54.9 million didn’t matter.

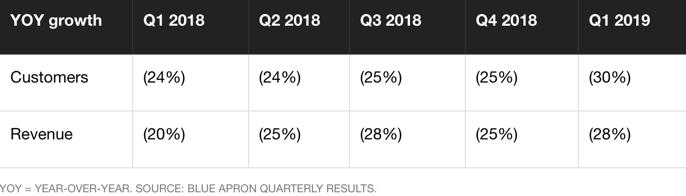

Blue Apron’s total number of customers fell 30% annually (but just 1% sequentially) to 550,000 during the quarter. Its revenue fell 28% to $141.9 million, missing estimates by about $8 million. Both figures mark continuations of Blue Apron’s prior woes:

The result is a share price that has collapsed by 90%.

Motley Fool writes that “Blue Apron’s 90% drop from its IPO price is a cautionary tale for businesses that can be easily replicated by bigger competitors.”

I have a different take though. Companies with no discernible ‘secret sauce’ i.e. barriers to entry a.k.a. economic moats can only expect to repel competition by scaling quickly. As soon as growth runs out, they are vulnerable to market penetration by competitors. And the lower the switching costs are, the higher the loss of revenue.

That’s what happened to Blue Apron. And that’s what Tesla fears as Mercedes-Benz, BMW, Audi, Jaguar and the whole lot of them ramp up their electric vehicle initiatives.

You stop growing and you die.

Is this a bubble?

In one sense, it is a bubble. 100%. Most of these companies are overvalued. Look at WeWork as a prime example given Galloway’s analysis. But I have no doubt they can conduct a successful IPO that values them in excess of $40 billion in the public market. So, in that sense, this is a clear bubble. And it’s been building for a while now – at least 5 or 6 years.

But, what is going on here is what I call a Gold Rush, a land grab due to the high optionality inherent in these companies. In fact, I described it five years ago. Here’s what I wrote about the new internet bubble:

My point here is that we are in a land grab in the technology sector as the industry moves away from the PC to a more mobile and cloud-centric universe. The dynamics of that kind of paradigm shift make manias likely, even inevitable because an investment in companies coming to prominence in this space right now is like buying a call option with huge amounts of implied volatility. That optionality is worth a lot of money – so much that it creates the kind of price movements that naturally lead to bubbles or manias.

This will end badly, of course. But not for everyone. For every Pets.com and WorldCom, there is an Amazon or an eBay. And it’s not always clear which company is which. Hence the high optionality inherent in this play.

The big problem is that most of the option value has accreted to the VCs in the private market. And the companies coming to market now are so large that there isn’t a lot of upside for punters in the public market. But, this mania can go on for a while. It’s already been five years since I called it frothy.

When this cycle ends, the mania will end. Perhaps the mania will pre-date the end of the business cycle. One thing is for sure, though: there will be enormous paper losses in the public markets. And I expect those losses to create collateral damage elsewhere. In the meantime, caveat emptor.

Comments are closed.