Get while the getting is good (and more on jobless claims)

Quick post here on jobless claims

Data collection difficulties

Data collection is a real challenge during this pandemic. And the US jobless claims data set is telling on that score. For one, the US Labor Department was forced a few weeks ago to change the way it seasonally adjusted its data because the scale of claims during the pandemic has been so large. I predicted this outcome in April and have been writing about it a lot since then. But, increasingly, the accuracy of even the raw data itself is being questioned.

So before I tell you what the data are saying, let me start there – with the problems this data set reveals.

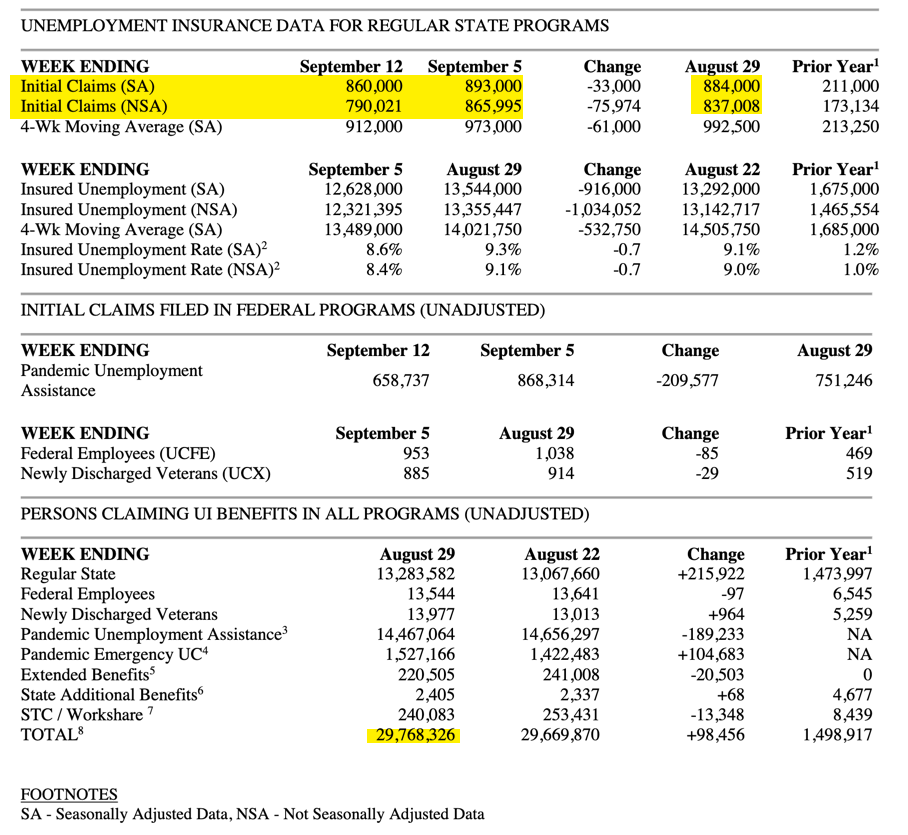

See the number marked in yellow at the bottom of the data chart above. That’s the US Department of Labor’s tally for the number of “persons claiming unemployment insurance benefits in all programs”. It is a raw number. It’s not seasonally-adjusted. And it is incredibly high at nearly 30 million.

The problem is that it might not be accurate. Here’s a Twitter thread on that topic from TJ Hedin of California Policy Lab, including a write-up on their site. The New York Times’ Ben Casselman has been on this as well.

The long and short is that we can’t really trust the data as much as we normally would. The scale of the crisis and the inability of US data collection systems to deal with it has made the resulting data sets less reliable. So, my focus has been mostly on directionality. What I want to see is what are the data telling us about where things are headed.

My View

And what the latest jobless claim data sets tells us is that the US labor market has stalled. For three straight weeks, we have seen the seasonally-adjusted claims figure close to 900,000, using the new methodology. Not only is that really high, the fact that it has stalled at that level tells you the flow of unemployed into the labor market remains high.

For me, it points to the likelihood that the US unemployment rate will rise from here. And while the unemployment rate does rise during the initial period of a recovery, we still have to be concerned that it crimps growth enough to reduce consumption, output, and investment. This is especially true in the absence of a fiscal offset to private sector financial distress.

Yesterday, was the Fed’s day. And a lot of people are talking about what the Fed did and said as if it’s meaningful in this context. I don’t believe it is. The Fed is done here – at least as far as the real economy goes. Nothing they said or did yesterday will have any durable impact on the real economy.

The Fed’s actions may be a boon for financial assets though. And people who want to take advantage of that are showing their cards. For example, Richard Branson, burned by a crisis for his travel and leisure-focused companies, is trying to raise $400 million via a blank check company -called an SPAC or special purpose acquisition company – to fund his next ventures. WHy would anyone give him another $400 million when his existing bets are being savaged? Animal spirits, that’s why. And Richard Branson understands this.

Another example comes from the FT, which points out that up to this point “in September, almost 24 per cent of money raised in the US loan market has been used to fund dividends to private equity owners”. These guys know that now is the time to cash in. Get while the getting is good.

So, that’s where we are right now. The real economy has rebounded a great deal. But the labor market remains weak enough that we should question the durability of that rebound. Meanwhile, the mania in asset markets continues unabated. The $50,000 question is whether the correction in NASDAQ share prices in early September is all we get for my September/October volatility. We have another month and a half to find out.

Comments are closed.