Credit Writedowns daily, tech-heavy edition

Let me focus on technology here today, rather than giving a more broad-brushed picture. This is more of an investor-focused post. But I am playing catch-up on a few of the tech stories. So I want to put them all together in one lot. And I think the daily is a good place for it then.

The big picture is that earnings growth at technology companies in Q2 is so far the third best sector at over 25% year-on-year behind energy and materials. Meanwhile revenue growth is 4th best at 13.6% behind energy, materials, and real estate. Even so, investors typically connote tech with growth stocks and have high expectations for growth in the sector.

1 Big Thing: Growth companies are all about intangibles now

I think Tesla is a perfect example of the kind of tech stock where growth expectations dominate, especially since there are no earnings to speak of. When Tesla CEO Elon Musk mused aloud about taking his company private, the first word out of my mouth was Dell. And I wrote up a piece on why that was a good and a bad comparison.

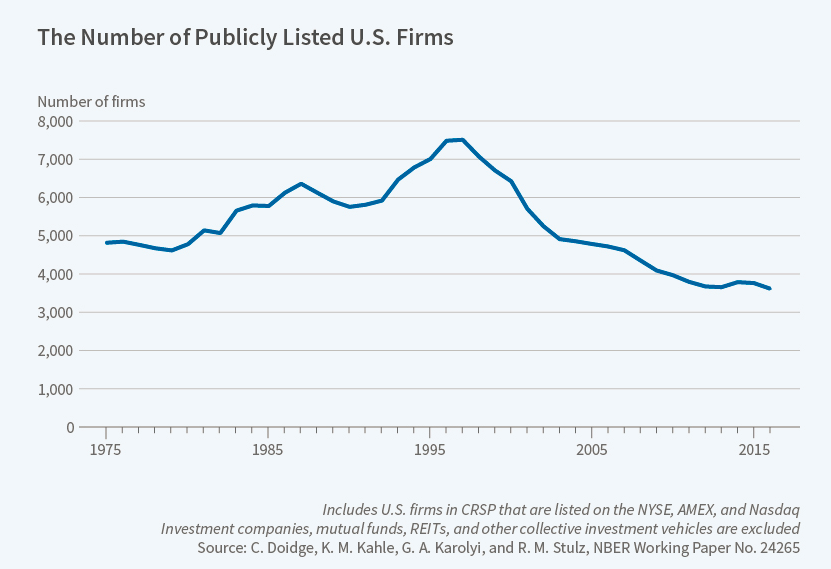

I think a better comparison is Uber, especially as it highlights something I touched on at the end of Tuesday’s daily. A recent NBER report highlights that fewer companies are public companies today than in the 1970s. The question is why.

Source: NBER

A New York Times article on the report practically begins with a quote from the author that “this is troubling for the economy, for innovation and for transparence”. And it ends saying:

There’s a broader problem. Our visibility into the inner workings of public companies isn’t great, but we know far more about them than we do private companies, which aren’t required to disclose nearly as much information.

But is that the issue here?

I certainly think companies are too big. Look at media space mergers, both vertical and horizontal. Look at the proposed Sprint-T-Mobile deal leaving the US with just three wireless carriers. That’s too much industry concentration and too much market power for individual firms in my view. But this is a separate issue, only related to the number of public companies because of the mergers that create that industry concentration.

For me, the issue is what kind of company is now a growth company. And we see this in technology in particular. The author of the NBER piece, René M. Stulz, actually spells it out well:

Until 2000, annual average capital expenditures of listed firms were almost never below 8 percent of assets. From 2002 to 2015, average capital expenditures of listed firms were never above 6 percent.9 While capital expenditures have fallen, average expenditures on R&D as a percentage of assets have increased considerably. Before 2001, average expenditures on R&D were always less than capital expenditures. From 2002 to 2015, average R&D as a percentage of assets always exceeded average capital expenditures as a percentage of assets.

A consequence of higher investment in R&D is that intangible assets have grown considerably in importance. There are other forms of intangible investment. Firms can invest in their workforce, in their organization, and in their brand names. Investment in these other forms of intangibles has grown as well. However, investment in intangibles is mostly expensed under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), so that it does not create assets on balance sheets. As a result, balance sheets that satisfy GAAP offer an increasingly distorted view of the assets held by corporations. Further, investments in intangibles make accounting earnings less relevant. The fact that GAAP accounting is less instructive about the economic value of firms with more intangibles works especially against young firms. An established firm with high intangibles will have an easier time convincing markets of its economic value. As a result, the growth in the importance of intangibles makes it less likely that young firms will want to join the exchanges and more likely that they will seek private funding or be acquired.

Translation: companies like Tesla are more likely to be private because, even though it is a manufacturing company, a large percentage of Tesla’s value is tied up in intangibles.

2. Tesla as Uber, not Dell

So think of Uber as the right Tesla comparison more than Dell. Uber is a company that had a swashbuckling founder CEO. And it has been in a hyper-growth phase, burning cash like mad. But Uber is a private company and it never went public. So it never had to submit to the kind of quarterly earnings scrutiny that Tesla must go through.

Perhaps, Elon Musk erred in going public at all. But, of course, Uber CEO Travis Kalanick got the sack.

My larger point here is that companies today are very different than companies 40 years ago. And it’s debatable whether the broader investing public benefits from being exposed to cash burning companies like Tesla for investment or whether the private markets are better at dealing with these companies.

We had a mania in cash burning companies in the late 1990s and that ended very badly. We may have a mania now, with private cash burning companies like Uber, whose implied value far exceed what will seem reasonable once the mania has passed.

For me, Tesla is more like Uber than it is Dell because it is an upstart in an existing industry, trying to change the dynamic and shift user preference to their offering. As a result, it isn’t even clear that Tesla or Uber will exist in 5 or 10 years’ time. My gut tells me that the public markets aren’t made for companies like that.

When I see the corporate social media company Slack raising $400 million+ dollars on a $7 billion valuation, I am happy to know it’s not a public company yet. Tesla is big but so is Uber. I’m not sure we want to see companies like that get publicly-traded.

For the counterpoint, see Marc Andreessen here. I’m curious to hear your thoughts.

3. Should companies IPO at all

Piggybacking on the public/private debate, here’s an interesting one using Spotify. If a company actually does go public, how should it do it? The CFO of Spotify took to the FT on Tuesday to argue that the IPO market is broken. Here’s what he wrote:

The process as we know it was born on October 13 1971, when Intel raised less than $10m from 64 underwriters. That valued the company at $58m after the fundraising. But IPOs haven’t changed much since 1971, and the process no longer works in many key areas. Among those areas are the quiet period, which limits what companies can tell investors ahead of the float, the lock-up rules that would have prevented our employees from selling their shares, and the size of the underwriting fees.

That is why Spotify, the streaming service where I serve as chief financial officer, opted for a direct listing instead.

But the real elephant in the room is the enormous discount that investors extract from newly-floated companies. Bankers told us that they try to price new listings so that they rise 36 per cent once trading starts.

That gain is what the institutional investors who buy IPO shares ahead of time insist on as their reward for taking the risk of buying into untested companies. With hits such as LinkedIn, the investors double their money in a day, while January’s ADTflop saw them lose 12 per cent. The economics makes sense for the investors, but the system penalises successful individual companies.

Hang on. Does it make sense for investors? I mean I just got finished making the case that a wave of IPOs by loss-making companies is effectively a lottery scenario for investors. And that lends itself to bidding up of asset prices.

Everyone thinks that one of these companies could be the next Amazon or the next Facebook. So they pile in. If you own enough of these companies and one of them eventually turns into the next Amazon, it won’t matter when the other 11 go bust like Pets.com or Webvan.

But the resulting mania from a lottery-style IPO wave leaves a lot of investors with huge losses. That’s what happened in the early 2000s and that’s what will probably happen here as well. Spotify is a loss-making company by the way. In fact, its losses through Q2 2018 were at 563 million euros were substantially higher than the 361 million euro losses for the first six months of 2017.

Something to think about

4. Over half of ICOs failed in Q2 2018

And since we’re talking about Initial Public Offerings, why not bring in the next mania, Initial Coin Offerings or ICOs for short.

Did you know that half of them failed this past quarter? And the ones that succeeded suffered massive losses.

Fifty-five percent of so-called initial coin offerings failed to complete in the second quarter, according to a report from the agency ICORating. That was 5% more than failed in the first quarter.

ICOs are a fundraising method in which companies and projects issue digital tokens structured like bitcoin or Ethereum. These tokens are sold in return for cash used to fund the development of the seller’s businesses. ICOs exploded from almost nothing to be a multibillion-dollar market in 2017, surging in popularity alongside the rise in the price of bitcoin.

The increasing failure rate came despite a rise in the amount of money being invested into ICO tokens. The report said 827 projects raised $8.3 billion through initial coin offerings in the second quarter of the year, compared with $3.3 billion in the first quarter.

This mismatch led ICORating to conclude that “the overall quality of projects has significantly worsened.” Fewer projects are attracting bigger sums, while many others languish with small sums or outright failure. The biggest ICO in the second quarter of 2018 was PumaPay, a cryptocurrency solution for merchants that raised $117 million in May.

The increased investment into ICO tokens comes despite poor performance in the second quarter. ICORating found the median return for tokens in the second quarter was a 55.5% loss, compared with a 49.3% gain in the first quarter. Bitcoin, the bellwether for the crypto and digital asset market, has declined over 50% this year.

That’s what a mania looks like, folks. It’s not pretty. And don’t think for a second this psychology hasn’t leaked into IPOs or share trading and valuation writ large.

5. Could Snapchat mark the peak of the social media wave?

For years, people seemed to have an unlimited appetite for signing up for social media services. Now some of those companies may be hitting a wall to adding new users.

On Tuesday, Snap, the maker of the Snapchat app, said it lost three million daily active users in the second quarter from earlier this year. It was the first time since the company went public in early 2017 that it had reported a decline in users.

Snap’s report follows similar trends from Facebook and Twitter. Facebook revealed late last month that its number of users in the United States was flat from earlier this year and that its users in Europe had fallen over the same period, even though its total number of members had grown. And Twitter, which has struggled for years to increase interest in its platform, also said in late July that its monthly active users had decreased by one million from earlier this year. After those disclosures, share prices of both Facebook and Twitter tumbled.

The declines and flattening growth raise questions about whether the social media companies have reached a saturation point in some markets, especially in developed countries. That may have been compounded by a steady stream of bad news about social media in recent months, which may have also deterred users. Facebook and Twitter have grappled with the spread of misinformation and foreign interference on their sites, for example, while Facebook has also been dealing with the misuse of user data.

There’s more on this from the New York Times here.

I think this is a good question because social has been driving the tech growth market. I have been saying that what we are seeing is a fundamental consolidation of the TMT sectors driven by the availability of ubiquitous and mobile high-speed bandwidth. Social only plays a peripheral role in that process.

We know where Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google are is going in terms of media content subscriptions, eating big media’s lunch. But where is the growth going to come from in social? And don’t tell me advertising. I don’t see it.

That’s all I got for today. Feel free to comment.

Cheers,

Edward

Comments are closed.