Donald Trump the risk taker, trade war edition

This is a follow-up to yesterday’s post about Donald Trump and confirmation bias. But it’s going to be a different beast altogether because here’s where I am going to lay out my thinking about Trump and trade. Let me cut to the chase: I think there is a high likelihood that Trump starts a trade war with China. I’ve written about this before – twice! But now I want to outline some possible economic and geo-strategic outcomes based on this. Some of these outcomes are pretty good. But some are catastrophically bad.

First, let’s look at Donald Trump, the risk taker. Here’s a profile that I think fits him pretty well — so well that I have inserted his name where appropriate – and added bold font for emphasis. The personality type is called “The Entrepreneur”:

People like Donald Trump always have an impact on their immediate surroundings – the best way to spot them at a party is to look for the whirling eddy of people flitting about them as they move from group to group. Laughing and entertaining with a blunt and earthy humor, people like Donald Trump love to be the center of attention. If an audience member is asked to come on stage, people like Donald Trump volunteer – or volunteer a shy friend.

Theory, abstract concepts and plodding discussions about global issues and their implications don’t keep people like Donald Trump interested for long. People like Donald Trump keep their conversation energetic, with a good dose of intelligence, but they like to talk about what is – or better yet, to just go out and do it. People like Donald Trump leap before they look, fixing their mistakes as they go, rather than sitting idle, preparing contingencies and escape clauses.

People like Donald Trump are the likeliest personality type to make a lifestyle of risky behavior. They live in the moment and dive into the action – they are the eye of the storm. People like Donald Trump enjoy drama, passion, and pleasure, not for emotional thrills, but because it’s so stimulating to their logical minds. They are forced to make critical decisions based on factual, immediate reality in a process of rapid-fire rational stimulus response.

This makes school and other highly organized environments a challenge for people like Donald Trump. It certainly isn’t because they aren’t smart, and they can do well, but the regimented, lecturing approach of formal education is just so far from the hands-on learning that people like Donald Trump enjoy. It takes a great deal of maturity to see this process as a necessary means to an end, something that creates more exciting opportunities.

Also challenging is that to people like Donald Trump, it makes more sense to use their own moral compass than someone else’s. Rules were made to be broken. This is a sentiment few high school instructors or corporate supervisors are likely to share, and can earn people like Donald Trump a certain reputation. But if they minimize the trouble-making, harness their energy, and focus through the boring stuff, people like Donald Trump are a force to be reckoned with.

I think this describes the president-elect remarkably well. I suggest you read the whole piece.

Now when you look at Trump the Entrepreneur through this prism, it explains not just his behavior on the campaign trail and in using Twitter, it also explains his “grab them by the pussy” mode of operating. I think it also explains how Trump the entrepreneur saddled four different businesses with so much debt that they were forced into bankruptcy. in short, Donald Trump is a man of action, who often leaps before he looks. That can mean unexpected success. But it means he is prone to getting things very wrong, and then having to improvise to clean up the mess.

This isn’t how traditional politicians operate, by the way. First of all, most politicians are frightened to death by uncertainty and assiduously avoid it to prevent tail risk. If you think about it from a decision tree perspective, a politician that has a choice between guaranteed but moderately bad outcomes and uncertain but potentially catastrophically bad outcomes is going to feel a lot of loss aversion pressure. Even a supposed maverick like Greek Premier Alexis Tsipras caved in 2015 – and went with a bad outcome to prevent a catastrophic outcome when the ECB threw down the gauntlet and threatened to collapse the Greek banking system.

But Trump is not that kind of guy. His overarching strategy is just the opposite – create uncertainty, be as unpredictable as possible and hopefully profit from this. He has even said this himself – multiple times:

- On China: “Well look, we have power over China and people don’t realize it. We have trade power over China. I don’t think we are going to start World War III over what they did, it affects other countries certainly a lot more than it affects us. But—and honestly, you know part of—I always say we have to be unpredictable. We’re totally predictable. And predictable is bad.”

- On Russia: “We need unpredictability. We’re so predictable. We’re like bad checker players, and we’re playing against Putin.”

- On Pakistan: “So when you talk about Pakistan—and let’s say they go rogue—I don’t want to really be saying what my initial thought is. … I want them to not know what my thought process is.”

- On ISIS: “I won’t tell them where and I won’t tell them how. … We must as a nation be more unpredictable. We are totally predictable. We tell everything. We’re sending troops; we tell them. We’re sending something else; we have a news conference. We have to be unpredictable. And we have to be unpredictable starting now. But they’re going to be gone. ISIS will be gone if I’m elected president. And they’ll be gone quickly.”

Trump’s view is that unpredictability is a weapon that will yield positive results both economically and in foreign policy. But, of course, unpredictability leads to policy errors too. If someone does something you didn’t expect them to do, your response could be made up on the fly and equally unpredictable – setting off a chain of response and reaction that leads to the catastrophically bad outcome. This is what most politicians try to avoid.

What about the situation with China then? The latest from Trump’s team is the nomination of Robert Lighthizer as US Trade Representative. Here’s what the Wall Street Journal says:

Mr. Lighthizer has three decades of experience arguing for punitive tariffs on overseas companies…

Still, Mr. Lighthizer has negotiating experience from his time in the Reagan administration, and if confirmed, he would take the lead in talks that could culminate in the bilateral deals that Mr. Trump’s team prefers…

Lighthizer himself said this about trade in 2008, though his views may have changed:

Mr. McCain may be a conservative. But his unbridled free-trade policies don’t help make that case.

Free trade has long been popular with liberals, and it remains so with liberal elites today. The editorial pages of major newspapers consistently support free trade. Ted Kennedy supported the advance of free trade. President Bill Clinton fought hard to win approval of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Despite some of his campaign rhetoric, Barack Obama is careful to express qualified support for free trade, even when stumping in the industrial Midwest.

Moreover, many American conservatives have opposed free trade. Jesse Helms, the most outspoken conservative in the Senate for three decades, was no free trader. Neither was Alexander Hamilton, who could be considered the founder of American conservatism.

…

Conservative statesmen from Alexander Hamilton to Ronald Reagan sometimes supported protectionism and at other times they leaned toward lowering barriers. But they always understood that trade policy was merely a tool for building a strong and independent country with a prosperous middle class.

In my view, the evidence, not just with Lighthizer but across Trump’s economic team, supports the notion that Trump will enact some sort of protectionist policy against both China and Mexico and maybe others. So my baseline assumption is that we are going to see trade restrictions. And now the questions are what those restrictions will be, how they will be negotiated, what the response will be from abroad and at the WTO, and what the economic consequences will be.

Since Trump is a risk taker, he may attempt to go it alone and enact unilateral protectionist measures that don’t require congressional approval or that may fall afoul of WTO rules — a leap before you look approach. The point would be to do something to make good on his campaign pledge regarding trade irrespective of the response from his own party, from China, or from the WTO.

Now the USTR website says the following:

For more than 30 years, Congress has enacted Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) laws to guide both Democratic and Republican Administrations in pursuing trade agreements that support U.S. jobs, eliminating barriers in foreign markets and establishing rules to stop unfair trade.

TPA does not provide new power to the Executive Branch. TPA is a legislative procedure, written by Congress, through which Congress defines U.S. negotiating objectives and spells out a detailed oversight and consultation process for during trade negotiations. Under TPA, Congress retains the authority to review and decide whether any proposed U.S. trade agreement will be implemented.

Fair enough. But nowhere here does the text address the potential for Trump to use an executive order and protect trade, rather than create agreements. This is what Trump wants to do – enact a 5 to 10 percent tariff on imports using an executive order – without the need for a Congressional vote. Is this unconstitutional? Some argue it is. But that doesn’t matter if Trump decides to take action first and ask questions later, something I see as likely.

That’s it regarding my speculation about what’s going to happen. But I want to make two further points. First, ostensibly Trump won because voters in states like Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin wanted him to do something to protect American jobs. I think that’s significant regarding how this gets debated and hashed out between Congress and the Trump Administration. Paul Ryan is saying right now that he won’t support tariffs. But public opinion could force Congress to make concessions of some sort. Let’s see.

Second, during the Great Depression, it was the creditor state, the United States that suffered the most in a world of slowing trade flows. To the degree that Trump creates trade barriers that further slow trade growth or even cause trade to contract, it is not clear to me that the US will be the ‘biggest loser’. I just want to flag this as an issue because, similar to the post-Brexit narrative that was bandied about before the UK voted to leave the EU, there is a prevailing narrative that tariffs will be economically devastating for the US economy. While I am anti-tariff and pro-trade, I think it’s better to suspend disbelief regarding likely outcomes to incorporate the widest possible breadth of potential scenarios.

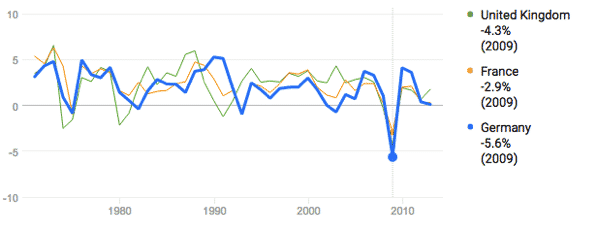

We don’t really know what protectionist measures the Trump administration intends to enact, nor what the response will be. We do know however that countries like Germany and China that have massive trade surpluses will hurt from reduced trade flows. We saw this in 2009 when the German economy contracted massively, more than other European nations.

Had China not gone into stimulus overdrive, we might have seen some very messy outcomes there too.

Right now, China is slowing and the re-balancing to domestic consumption is still incomplete. The massive trade surplus in China says the country needs trade flows to remain buoyant. And so if there is a trade war, given the large increase in debt in China, I would look there for the first signs of economic turmoil – as well as for aggressive or unexpected geo-strategic responses.

In some potential future, China would blow off the trade barriers and reach a negotiated agreement. In another potential future, China would allow the Yuan to fall limit down every day until the market adjusted to a new level at 8 Yuan to the US dollar or more. In some other potential future, China would take a scorched earth policy economically and geo-strategically, resorting to a disproportionate response that includes both economic and military objectives. It is this last outcome that we should fear.

Comments are closed.