Defining crisis and predicting outcomes in an environment of maximum uncertainty

Twelve years

I have been at this for 12 years now. It seems remarkable that I have been writing this site, Credit Writedowns, for that long because I can remember the early days like they were yesterday.

I was thinking about this fact – that I’ve been doing this for twelve years – when I woke up and had my morning coffee. And I realized that these posts were ‘born in crisis’ so to speak; I started this site in the middle of the last crisis. So I decided to write something today connecting the past to the present.

Here’s my thinking on this. Let me lay it out because there are multiple threads. First, again and again I come back to the fear that we’re living through another Great Depression. That’s something that I felt, that many of us felt, during the Great Financial Crisis into which this site was born. And what I’ve taken away from that episode is that the US economy (and the world economy) is more resilient today than it was then, that policy makers will do their utmost to prevent that outcome

I don’t think our worries about another Great Depression were unfounded. It’s just that – despite our collective bellyaching over the details and derision directed toward the powers that be – they actually did a fairly good job. Let’s give them some credit for that. We may not like how this was achieved. And we may feel the unfairness of the solutions has made populism great again. Nevertheless, we have to concede the 2007 outcome was superior to the 1929 one or the 1873 one, for that matter.

That’s my biggest takeaway after writing this site for twelve years.

Outcomes

But acknowledging the relative success of the past doesn’t put my mind to rest today. The challenges facing policy makers now are of a different sort than they were 12 or 13 years ago. And the real economy blow is of an order of magnitude much greater than anything we have witnessed in our lifetimes. Look at this graphic linked below.

Jobless claims time lapse. WATCH https://t.co/xBFFjhH0tK

— Edward Harrison (@edwardnh) April 2, 2020

I can’t describe in words what that graphic shows. I can try, but I was simply blown away at visualizing how much higher the numbers today are than they ever were. And I don’t think you can describe that emotion. You have to see it.

Even so, I still can’t help going back to my first several posts here because they told us in real time – and accurately – that we were already in a recession and that worse was to come.

I re-read some of the posts. And I have to laugh because, for me, they are a reminder about how much my economic views regarding appropriate policy responses have shifted in the intervening twelve years. At the same time, the core predictive ability is there. And so, these days that’s what I tend to focus on: outcomes.

Europe

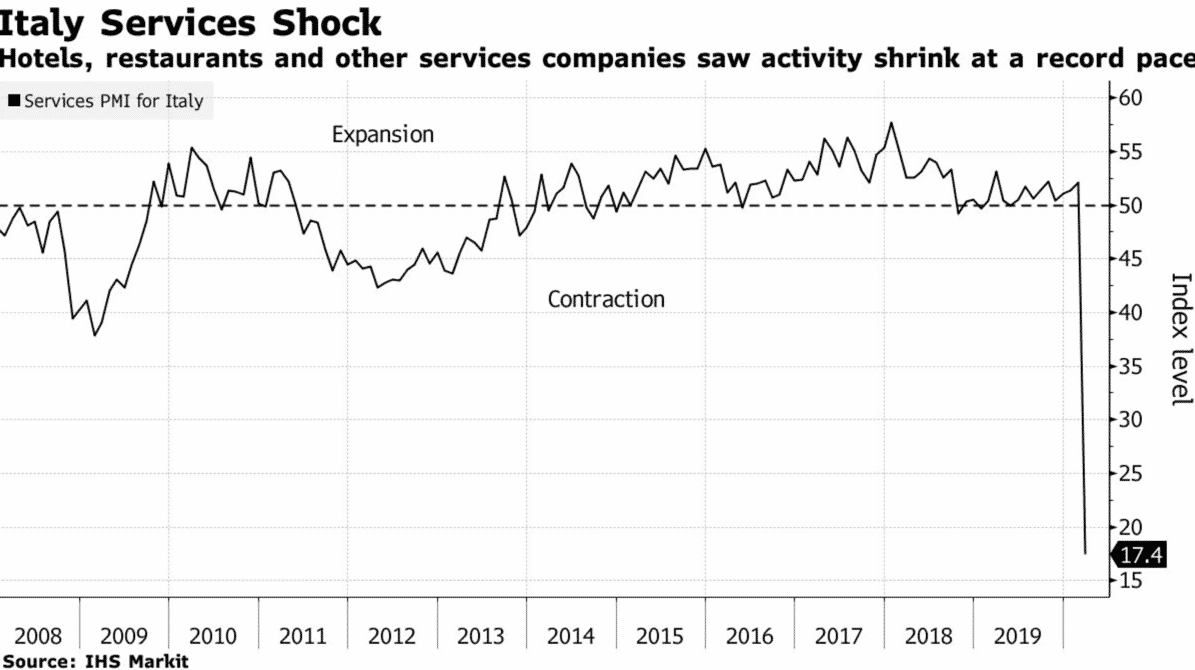

Going back to the graphic linked above, how do we reconcile the price movements in asset markets with the unprecedented nature of this downturn? For example, I saw today that the eurozone is estimated to have shrunk 10%, with worse still to come. Look at the Italian economy.

Would it be hyperbole for me to describe this as a Depression? Look at the fall in output. These aren’t numbers from a recession. It’s an absolute cataclysm economically, with real suffering and pain apart from the deaths and plague besetting the country.

How do you ‘fix’ that? This is a policy question, isn’t it? And so, I’m not going to answer the question directly. I will simply point to the policy limitations of the euro area’s structure, where there is a common currency with a powerful central bank but no equivalent fiscal authority. The late British economist Wynne Godley presciently described it like this in 1992, as the euro area’s structure was being developed:

…The incredible lacuna in the Maastricht programme is that, while it contains a blueprint for the establishment and modus operandi of an independent central bank, there is no blueprint whatever of the analogue, in Community terms, of a central government. Yet there would simply have to be a system of institutions which fulfils all those functions at a Community level which are at present exercised by the central governments of individual member countries.

[…]

…It should be frankly recognised that if the depression really were to take a serious turn for the worse – for instance, if the unemployment rate went back permanently to the 20-25 per cent characteristic of the Thirties – individual countries would sooner or later exercise their sovereign right to declare the entire movement towards integration a disaster and resort to exchange controls and protection – a siege economy if you will. This would amount to a re-run of the inter-war period.

If there were an economic and monetary union, in which the power to act independently had actually been abolished, ‘co-ordinated’ reflation of the kind which is so urgently needed now could only be undertaken by a federal European government. Without such an institution, EMU would prevent effective action by individual countries and put nothing in its place.

We worried about this during the European sovereign debt crisis – and I think, rightly so. The fear that the euro area can’t deal with an economic crisis has to be much greater now then – because the numbers are that much greater, the economic pain is that much greater, and the human suffering is unbearable.

Right now, the European Union is squabbling over whether to use the European Stability Mechanism or so-called coronabonds to give fiscal relief to its citizens. And allegedly, there are only 4 hold outs for coronabonds in the eurozone: Germany, Netherlands, Austria, Finland. That’s what Italian media are saying. The French haven’t taken a position. But when they do, I think it will be decisive. That’s where Europe will head, for better or worse. Let’s see what happens.

However you look at it though, you have to have Wynne Godley playing in the back of your mind.

…If a country or region has no power to devalue, and if it is not the beneficiary of a system of fiscal equalisation, then there is nothing to stop it suffering a process of cumulative and terminal decline leading, in the end, to emigration as the only alternative to poverty or starvation.

My take

I look at all of this and I come to three conclusions.

- We are in a Depression – not a recession, a Depression. And I think the dynamics of a Depression are different than they are in a recession. How they’re different, we will need to establish. But, at a minimum, it entails hysteresis. Think about Godley’s 1992 comments above referencing ‘permanently’ higher unemployment.

- Asset markets do not reflect the economic Depression. As I write this, oil prices are rallying on the back of some dubious commentary from US President Trump. It’s almost as if the worst is not yet to come, when, in fact, we’re only just beginning on this lockdown journey. I believe asset markets will come to reflect the economic reality in due course though. And that will compound the downside impact from the real economy.

- Politicians won’t stand idly by as this happens. The human toll of all of this is immense. That’s why, for one, I told you I expected the premature lifting of lockdown as a backside response. Trump has given up on that policy response for now. But, the longer this goes on the more palatable that outcome will appear. And to the degree we don’t get that response, there will be others, simply to stop the human suffering. Some of these responses will be good but others will be bad.

This is an event that’s not comparable to 2008 or any other economic event we have seen in our lifetimes. And the scale of both the global health crisis and the interlocked global economic crisis is an order of magnitude greater than anything any of us have have ever witnessed. I don’t think the scale of this has fully sunk in yet. It will do eventually though. And that’s when the second and more draconian reaction from markets and policymakers will come.

The first market and policy response is now behind us. But the real economy impact mostly still lies in front of us. And that means that, right now, we are moving from a point of near-term certainty to maximum uncertainty where its most difficult to predict outcomes.

Stay safe.

Comments are closed.