There’s no dominant theme I want to discuss today. But, there is a lot of news flow. So I thought it would be a good time to take stock of what’s happening in the economy and financial markets, without presenting an overarching theme. Some stories follow below, with a few thoughts of my own.

Oil sector pain

Oil services giant Baker Hughes reported a massive $10.2 billion loss in Q1. That’s because, as they had already warned last week, the firm would take a $1.5 billion charge and a $14.8 billion writedown of goodwill due to the reduced value of its oilfield and equipment unit.

When excluding those impairments and other charges, the oil field services company’s adjusted net income was $70 million, or 11 cents per diluted share, for the first quarter. That’s in line with analysts’ average estimate, according to Yahoo Finance.

Goodwill accounting charges are cashflow neutral. But, companies don’t take $15 billion impairment charges unless something significant and long-term has occurred. This is telling you that Baker Hughes believes their assets are permanently impaired in a massive way. It’s telling you that we are in a whole new world in the oil sector.

Their press release last week also said they “approved a plan to reduce 2020 net capital expenditures by over 20% versus 2019 net capital expenditures.”

This does not bode well for the rest of the industry.

Canada oil sector bailouts

Canada is going to be hit hard by this. And so, Reuters is reporting that Export Development Canada (EDC) is going to help provide liquidity to small producers, essentially a bailout since I expect these loans will go bust. Reuters says:

Canada’s export credit agency on Wednesday said it would backstop loans to hard hit oil and gas producers, in the latest move by Ottawa to free up credit for the struggling energy industry.

Banks are reviewing borrowing limits in the sector and could head off bankruptcies of small and mid-sized energy firms pummeled by the collapse in oil prices.

[…]

Under the program, the agency will backstop up to 75% of a bank loan, to a maximum of C$100 million, for at least one year, the document said.

“EDC will provide an incremental guarantee of over and above the (banks’) borrowing base to partially mitigate the current oil prices,” it said.

The program is targeted at Canadian companies that pump 100,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day or less, according to the presentation.

Small and mid-sized oilfield service companies and firms that ship, process and store oil and gas would also be eligible, EDC spokeswoman Jessica Draker said.

Think of this in the context of the overall market narrative. The narrative now is that government largesse will help tide firms over until the economy restarts. That’s why stocks can do as well as they have done of late. The downside risk to that narrative is that these firms go bust anyway. But, in this case, the Canadian government would absorb the losses, not the banks.

Crude oil build

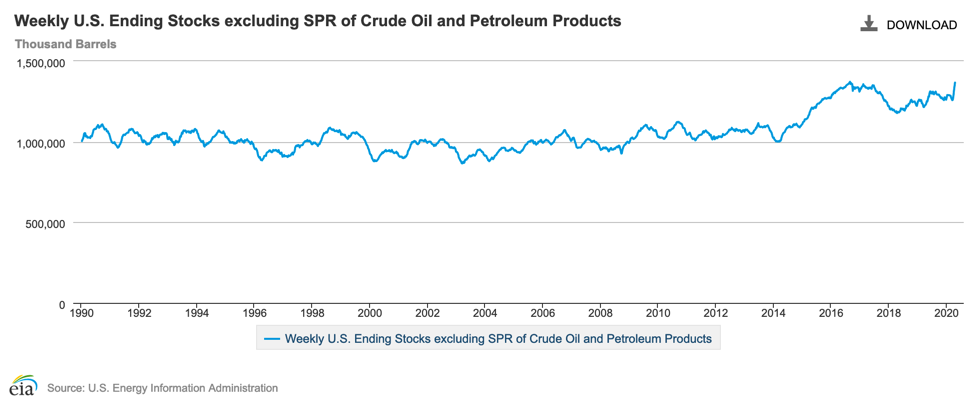

The latest US EIA report yesterday showed a build in crude and product of 25.5m barrels in the week to 17 April. That’s just short of last week’s record build. And, over the last 5 weeks, all product and crude inventories are up a massive 109.1m barrels. That’s 3.22m bpd. We are now at 1.37bn barrels of US crude and petroleum product inventories excluding the special petroleum reserve.

And while I thought this was unsustainable, the long-term reserve chart shows the build coincides quite nicely with the US shale oil revolution, with inventories rising from a range near the 1bn barrel level after early 2014. The peaks in 2016 and 2017 because of the shale bust are right around the levels we are hitting now. My conclusion, then, is that we have been ‘oversupplied’ for sometime. But, it’s only this massive demand drop that has made plain how unsustainable the shale revolution was.

The excess supply that caused negative prices on May 2020 WTI contracts isn’t just a US problem because of landlocked Cushing, OK; it is a global thing. The Times of London is reporting that “oil majors and commodity traders are paying up to six times normal rates to store surplus crude in supertankers at sea as they try to cope with an unprecedented global glut.” They say that “companies are paying about $180,000 a day for three months’ use of very large crude carriers (VLCC) that can each store two million barrels of oil, according to EA Gibson Shipbrokers. That compares with rates of between $30,000 and $40,000 a day in February.”

Muppets vs. Sharks

Yesterday, I told you about my sister’s friend who wanted to speculate in oil. Well, she’s not alone. The FT is reporting that retail investors and day traders around the world are the ones who got burned really badly as prices went negative, whereas big-time commodity traders and oil funds made out like kings. They’re billing it as a ‘Muppets vs. Sharks’ episode.

Interactive Brokers took an $88 million hit because retail investors incurred losses (on oil trading) in excess of the value of their accounts. The FT story is a good account and it highlights what I said on Real Vision a few days ago when talking about this: stick to your knitting. Oil and commodities are complicated. Do not invest in these products if you don’t know what you’re doing.

Vol sale pain

I wouldn’t bill this as a ‘Muppets vs Sharks’ episode. But, it bears mentioning that a major Canadian pension fund got out over its skis selling volatility and ended up losing $4 billion for public sector employees during the market meltdown.

The Globe and Mail reported Tuesday evening that sources familiar with the situation say AIMCo has lost more than $4 billion through a volatility-based investment strategy. The story was first reported by Institutional Investor, a trade publication based in New York that follows pension funds.

AIMCo has a portfolio of about $119 billion, which represents hundreds of thousands of Albertans’ pensions and accounts like the province’s Heritage Savings Trust Fund.

Dénes Németh, AIMCo’s director of corporate communication, said the pension manager does not comment on the performance of active investment strategies other than to its clients.

“The level of volatility that markets experienced in March 2020, the result of the COVID-19 pandemic, during which volatility rose faster, and on a more sustained basis than at any other time in history, is exceptional,” he said.

“AIMCo acknowledges that it is not immune to the challenges, unique as they may be, that institutional investors around the world have experienced.”

AIMCo’s portfolio is broadly diversified, he said, adding that it’s well positioned in the long-term.

As Leo Kolivakis says of the incident, selling volatility has been a profitable yield-enhancement strategy for many over the past several years. He thinks it has produced 6-8% gains annually. But we saw Volmaggeddon in February 2018. And you would think people were chastened by that incident. Apparently not.

The reality is that someone has to be selling volatility if someone else is buying it. The question is whether we have reached a permanently higher volatility scenario for the foreseeable future. I think the answer is yes.

Canadian pension fund losses in Neiman Marcus

Let’s stick with Canadian pension funds here for another second. Back in January 2018, the Globe and Mail headlined an article “CPPIB paid $6-billion for luxury retailer Neiman Marcus. The bet backfired.“The gist of the article was that the Canadian Pension Plan Investment Board had used its own in-house private equity group to become part owner of high-end US retailer Neiman Marcus in a 2013 LBO. And this particular investment had already gone pear-shaped.

Retailers are suffering during the coronavirus pandemic. And Neiman Marcus is widely reported to be a likely casualty. Neiman Marcus hasn’t filed for bankruptcy yet. But even Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick expects Neiman Marcus to go bankrupt now. The question is about restructuring versus liquidation because that has economic and employment implications. Neiman Marcus has furloughed 14,000 employees.

The Wall Street Journal is saying Saks Fifth Avenue parent and Canadian retailer Hudson’s Bay is a potential buyer. They could make an offer for Neiman after it files for bankruptcy.

But if Hudson’s Bay doesn’t step in, CPPIB and Ares, its LBO owners, will have to decide how they want to proceed. Although private equity companies are telling the Trump Administration their portfolio companies need bailouts too, I am sceptical these companies will receive government largesse. They missed out for a second time on any US government money when the latest stimulus bill passed earlier in the week. So the LBO partners are on the hook to help in a restructuring. How they decide could set a precedent.

One more thing here too. I know that private debt is one differentiating feature of Canadian pension companies. Many of the largest ones have brought this expertise in-house. And the returns have been both very good and uncorrelated with stock and bond returns. I talked to Jim Leech, the former CEO of the Ontario Teacher’s Pension Plan, about it for Real Vision earlier in the year (link to video here). My question is whether this outperformance and non-correlation lasts. I intend to ask Canadian pension fund expert Leo Kolivakis about it in an interview tomorrow. Watch for that next week on Real Vision.

Does 60-40 work anymore?

Along the same lines, I saw Robin Wigglesworth at the Financial Times, asking about the effectiveness of a traditional 60% equity 40% bond portfolio. What he points out is that in the first quarter, 60-40 had one its worst performances since the 1960s. So, despite having its highest volatility-adjusted return in over a century this past decade in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis, we could be looking at under-performance going forward. Why?

Goldman now warns that the longer-term outlook is for lower returns and “larger and more frequent drawdowns” for the once-trusty 60-40 portfolio. “Balanced portfolios have become more risky,” Christian Mueller-Glissmann, a strategist at the bank, warned in a recent report.

And with increased volatility (one reason to doubt the efficacy of vol selling yield enhancement strategies), you aren’t going to get compensated via the bond portion of your portfolio because yields are so low. To get the same returns you have to increase risk and duration, which actually means your risk-adjusted returns are lower. For defined contribution investors, that’s a recipe for disaster if they’re close to or in retirement because it could permanently impair their nest egg.

I suggest you read the whole piece. It’s food for thought about asset allocation and likely investment returns over the coming decade.

Last comments

I saw a few more stories of note like Mitch McConnell telling states and municipalities to file for bankruptcy. That tells you a hit to public sector pension funds is coming.

There was also a story on Brazil cutting rates by 75 basis points, which I thought was interesting given how emerging market countries have traditionally been loath to cut in recessions for fear of currency risk.

And finally, Argentina missed a payment on its sovereign debt yesterday. They’re likely to go into another formal default. It’s a reminder of what reaching for yield means in terms of potential loss of principal.

There’s a lot going on right now. So I hope this was helpful in filling in some of the missing pieces. For those of you who aren’t subscribed, you can sign up for weekday emails here.

Comments are closed.