The problem with Europe

I have been troubled by the lack of policy space in Europe for some time now, particularly as it concerns Italy. But this is coming to a head for me this morning, with the German government auctioning 10-year paper at 24 basis points below zero and some German interest rates almost 70 basis points below zero. So I want to explain what I see as the challenges ahead as well as the opportunities.

By the way, this is one of the occasional free Credit Writedowns posts I write. If you like what you read please consider subscribing to the newsletter. Plus, I have just started running a limited promotion for paid subscriptions.

Back to Europe

Currency Sovereignty

In Europe, it all starts with the currency. And that’s because the euro is not a national currency which individual member states can control in exigent circumstances. It is a common currency managed and administered by the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem of national central banks.

This is different from national currencies like the British Pound, where, despite the outward appearance of an independent central bank, the national government has absolute dominion over the nation and the central bank administering the currency. That’s because, with national currencies, the central bank has been delegated authority by the government to operate on its behalf, setting monetary policy and operating as monopoly issuer of banknotes and reserves. The national central bank may be granted independence to instill some level of fiscal discipline. But it still an actor which works at the pleasure of the government.

In the Eurozone, there is really no equivalent elected government body to the ECB. So, when push comes to shove, the ECB’s unelected officials make the critical decisions that involve sovereign debt and crisis. We saw this during the sovereign debt crisis as Mario Draghi said the ECB was “ready to do whatever it takes” to preserve the euro. And while the ECB’s judgement did not work out well for Greece (or Spain, Portugal and Ireland) in avoiding crisis, it did spare Italy.

The Euro setup is dysfunctional

The eurozone survived this first sovereign debt crisis intact. But the framework is quite dysfunctional. It ensures a pro-cyclical shortfall of demand because the eurozone’s rules mandate government fiscal rectitude at all times. And this is especially onerous at troughs in the business cycle when private sector demand contracts.

Italy is the best example here. A lot of political economists believe Italy needs some measure of structural reform to re-animate growth. But Italy has three problems. First, there is a government debt overhang that is so large that, despite the eurozone’s 3% deficit threshold, Italy can only run deficits of 2% of GDP in order to meet the common currency’s debt and deficit criteria.

But, then you add to this the fact that Italy’s banks are undercapitalized and larded up with non-performing loans and you have a lack of credit supply, even if demand for credit by creditworthy borrowers were high. But demand for credit by creditworthy borrowers is weak because consumption demand is weak. And, unless the demographically-challenged country is able to ‘steal’ demand through exports as the equally demographically-challenged Germany does, that weak domestic demand is a killer for growth.

If Italy were monetarily sovereign, it would simply deficit spend, with the government adding the demand needed to rectify the nonperforming loan problem. And the currency would likely depreciate as a result, making exports easier and adding yet another avenue to growth.

But Italy isn’t monetarily sovereign. It is a member of the eurozone. And the rules – that the current government seems bent on breaking – dictate that Italy cut spending to meet deficit hurdles which will reduce the government debt to GDP load toward the eurozone’s magic 60% bogey.

That’s never going to work.

Outcomes

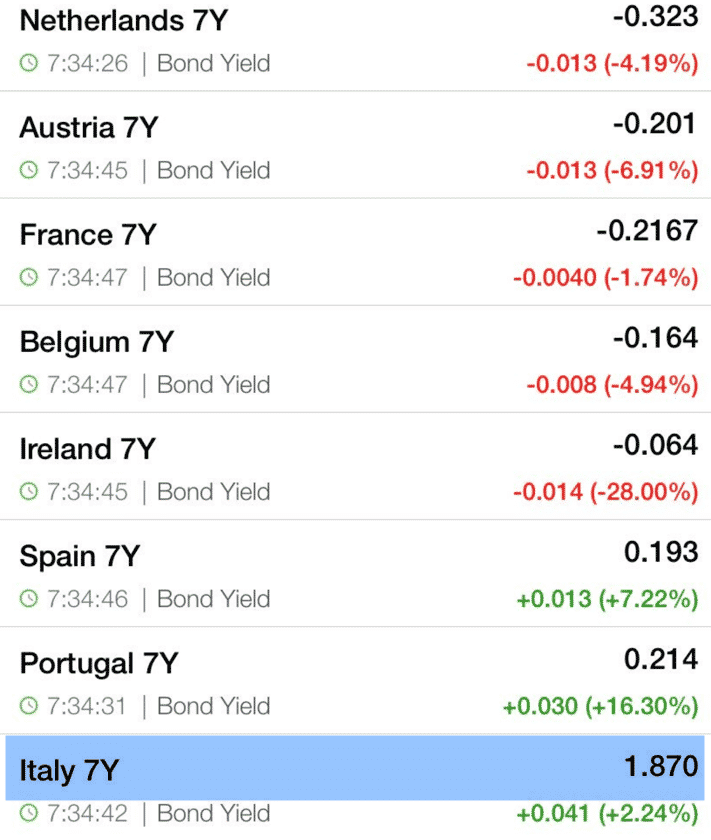

The perversity of the situation is clear if you look at 7-year yields across the eurozone.

Source: Investing.com

If you didn’t notice that Italy is the big outlier there, I highlighted it for you. The differential between Portugal and Italy is all about default and currency redenomination risk. After all, Italy’s 1-year bond is trading at just under 5 basis points. What the spread tells you is that people see an existential crisis for the eurozone coming to a head in the next few years – with Italy at the center of that crisis.

What kind of outcomes should we expect then?

First, the present situation would be unsustainable in a eurozone-wide economic downturn when private demand is falling more rapidly. That would require greater cuts than at present. And Italy’s government is already balking at the deficit and debt rules right now.

These rules are not going to be sacrificed for Italy’s sake. That much is clear given the mood of electorates in countries like Germany. So, Italian fiscal stimulus as a sanctioned policy course is off the table. Moreover, other countries would also be looking to cut deficits too. And any stimulus in places like Germany that have some headroom would benefit the domestic economy, not Italy’s. So there will be only limited upside there as well.

So, either the eurozone set up some kind of eurozone-wide fund or eurozone-wide debt vehicles — or we will have a crisis. How likely is the eurozone to do any of that before a sovereign debt crisis hits? I say, it’s not at all likely. And so, I see a crisis with Italy at it’s center as all but inevitable.

Conclusions

So, Germany is getting paid to borrow right now. Rates could go lower, sure. But it won’t help Italy, as we see from the yield spreads now. We might even see divergence in other more vulnerable countries as well. And the flight to quality of crisis will make divergences even larger.

To the degree the ECB does anything, it has already said it would do so proportionately, meaning it’s not going to simply go in and tee up Italian bonds because that’s against the rules. It would be considered monetary financing. The most the ECB could do is keep Italy’s yields in check as a quid pro quo for deficit reduction and structural reform – what we saw in Greece.

And that won’t fly politically. This is combustible stuff, frankly. For me, Europe is where the exigent problems in the next global downturn will be – both economically and politically.

Comments are closed.