The post-coronavirus view of Italian government debt

At the weekend, I noticed that the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte was still touting so-called coronabonds to deal with the devastating impact of this pandemic on Spain and Italy. For some northern European policy makers, this is a complete non-starter.

And while this lack of policy cohesion in the eurozone is troubling, it’s not unexpected. So, I don’t want to overplay the potential for a breakup of the eurozone. Even so, I do think the issues highlight the problems Italy faces. And so, I want to outline some of the missing pieces no one is talking about below.

The eurobonds debate today

This argument around coronabonds is, in many ways, the same debt mutualisation conflict we saw during the European sovereign debt crisis. And it goes to the heart of what the eurozone is. I think it’s meaningful that the French have now taken sides though. Here’s Bloomberg:

Conte evoked the risk of market contagion if European leaders fail to act on pressure from Italy and Spain, according to a Sunday interview with Germany’s Sueddeutsche Zeitung. His words echo a warning from French President Emmanuel Macron last week that it’s necessary for the EU to “issue common debt with a common guarantee,” and that failure to rise to the occasion would lead to the bloc’s collapse.

[…]

Spain proposed creating a European fund of as much as 1.5 trillion euros to tackle the recovery effort, according to a copy of the paper obtained by Bloomberg. The fund would be financed through perpetual EU bonds to keep national public debt levels in check. Grants would then be made to member states through the EU budget.

Spain’s economy could contract this year by more than 12% in a worst-case-scenario forecast by the country’s central bank. The economic shock could push the unemployment rate to as high as 21.7% this year, undoing gains achieved in the aftermath of the 2008 global recession. At nearly 14%, Spain’s unemployment rate is already one of the highest in the developed world.

If you’re going to issue eurobonds, this would be the time to do it – during a pandemic where economies are collapsing through no fault of any fiscal authorities’ rectitude. It’s not like the Spanish were flouting EU fiscal rules. They were simply hit by a once-in-a-lifetime natural disaster.

The Germans and the Dutch want to use the European Stability Mechanism, set up during the sovereign debt crisis, to address the budgetary issues. Italy is opposed. Bloomberg again:

Conte said the European Stability Mechanism rescue fund, Germany’s preferred tool to address the economic impact, “has a bad reputation in Italy.” He added it’s not about pooling past or future debt but rather about “an extraordinary effort” to deal with the current situation, according to Sueddeutsche.

The Germans, the Dutch, the Austrians and the Finns aren’t going to budge here. As I said back on the eighth, “the Italians and Spanish will not get what they want until the threat of redenomination enters the picture.” That’s still my view, even now that France has chosen the southern European side over the Germans. You have to have a real threat of breakup before the Germans and their allies agree to several and mutual debt.

The origins of the crisis, part one

How did we get here?

A decade ago I explained from a German framing “How Belgian debt, Italian anarchy and Greek profligacy led to economic chaos in Europe“. The way the Germans look at it, the southern Europeans (and the Belgians) were profligate, fiscally irresponsible, and had no one to blame but themselves for their problems. And while the Belgians dug themselves out of this hole, the others have not.

The Germans don’t want to issue eurobonds because they don’t want to be on the hook for this so-called profligacy. They want the Italians and the Greeks to do what the Belgians have done and work their debt down as a percentage of GDP. And if that means imposing fiscal austerity, then so be it. That’s the German view.

There’s another view. And I am sympathetic to it. With regard to Italy specifically, it comes in two parts. First, there is the legacy debt part. Here’s a late 2018 post on “Understanding The Huge Italian Public Debt As A Legacy Of The Oil Crisis“:

The debt is a legacy of the eighties, when the minister of the Treasury, Beniamino Andreatta, and the governor of the Bank of Italy, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, signed the “divorce” between the two institutions. Before, the Bank had to buy the government’s bonds that were not placed on the market, assuming this way the burden of financing state requirements. Basically, the Bank was assuring the success of government bonds’ auctions by printing the money necessary to buy the unsold bonds. The divorce enshrined the independence between the ministry and the Bank and had multiple reasons behind it.

The eighties were the years of the oil crisis which boosted the inflation really high all over the world. As Ronald Reagan and the governor of the Federal Reserve decide to kill inflation, the Bank of Italy had to follow like all the other major banks around the world. The Italian lira was devalued by 40% against the dollar and in this context Andreatta and Ciampi decided to sign the divorce, freeing the bank from the obligation of buying the unsold bonds which could not be placed in the market.

The aim was to stabilize the lira and at the same time grant the Bank with more autonomy in its choices within monetary policies. However, after the divorce, the state had to sell out bonds at much higher interest rates and the cost of the public debt, which was until then absorbed by the currency, started to become greater and greater. As the Bank of Italy stopped monetizing the public debt, the latter went out of control. In 1980 the Italian public debt was at 57,7% and by 1994 it grew by 124,3%.

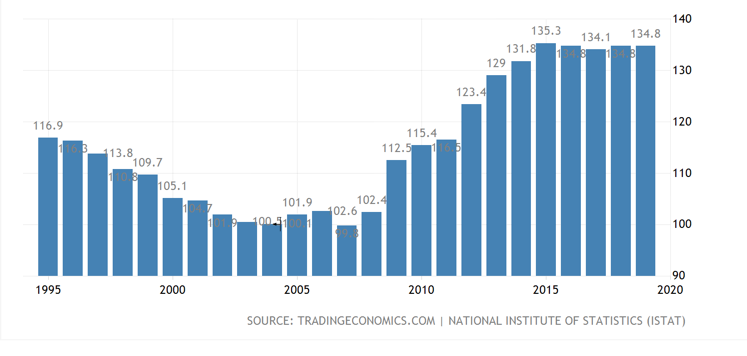

So, when the Maastricht Treaty was enshrined in 1992 to create the euro. Italy wasn’t eligible to meet the criteria – which included low government debt. The fudge was to allow the Italians (and the Belgians) to meet an arbitrary 60% government debt to GDP hurdle through reducing their debt toward the limit rather than remaining under it. Up until 2007, both the Belgians and the Italians were successful in this regard. But afterwards, Italy’s government debt numbers ballooned as back to back crises – The Great Financial Crisis and the sovereign debt crisis – crushed the economy.

Belgium, which came less undone in 2007, was not impacted in the sovereign debt crisis, and, therefore, has escaped relatively unscathed as a result.

The origins of the crisis, part two

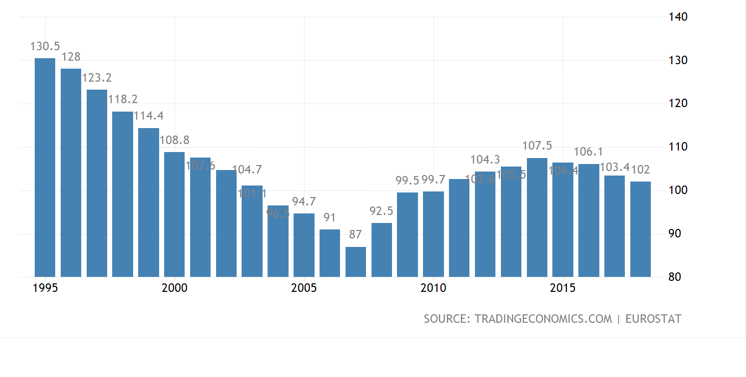

I mentioned back on the eighth that the Italians have been more fiscally responsible on primary surpluses than the Germans. In essence, their legacy debt problem has meant that, to meet Maastricht criteria, they have been forced to run a more fiscally austere budget to compensate both for interest payments and the need to get budget debt down as a percentage of GDP. This has been negative for growth. And that’s the second answer on how we got here.

Dutch economist Servaas Storm explained in a paper last year, entitled “Lost in deflation:Why Italy’s woes are a warning to the whole Eurozone“. Here’s the crucial bit:

Using macroeconomic data for 1960-2018, this paper analyzes the origins of the crisis of the ‘post-Maastricht Treaty order of Italian capitalism’. After 1992, Italy did more than most other Eurozone members to satisfy EMU conditions in terms of self-imposed fiscal consolidation, structural reform and real wage restraint—and the country was undeniably successful in bringing down inflation, moderating wages, running primary fiscal surpluses, reducing unemployment and raising the profit share. But its adherence to the EMU rulebook asphyxiated Italy’s domestic demand and exports—and resulted not just in economic stagnation and a generalized productivity slowdown, but in relative and absolute decline in many major dimensions of economic activity. Italy’s chronic shortage of demand has clear sources: (a) perpetual fiscal austerity; (b) permanent real wage restraint; and (c) a lack of technological competitiveness which, in combination with an overvalued euro, weakens the ability of Italian firms to maintain their global market shares in the face of increasing competition of low-wage countries. These three causes lower capacity utilization, reduce firm profitability and hurt investment, innovation and diversification. The EMU rulebook thus locks the Italian economy into economic decline and impoverishment.

Translation: Italy has followed the rules. And doing so has crushed their economy, making the problem even worse.

Perversely, the Germans and the Dutch have benefitted. How? Because in a currency union with the free movement of capital, money flows from countries that are considered risky like Italy to countries considered safe like Germany and the Netherlands. That increases Italian borrowing costs and decreases German and Dutch costs.

Back in 2011, Paul de Grauwe used Spain’s experience during the sovereign debt crisis to explain, with the UK, which has monetary sovereignty, as a direct contrast:

Suppose that investors fear a default by the Spanish government. As a result, they sell Spanish government bonds, raising the interest rate. So far, we have the same effects as in the case of the UK. The rest is very different. The investors who have acquired euros are likely to decide to invest these euros elsewhere, say in German government bonds. As a result, the euros leave the Spanish banking system. There is no foreign exchange market, nor a flexible exchange rate to stop this. Thus the total amount of liquidity (money supply) in Spain shrinks. The Spanish government experiences a liquidity crisis, i.e. it cannot obtain funds to roll over its debt at reasonable interest rates. In addition, the Spanish government cannot force the Bank of Spain to buy government debt. The ECB can provide all the liquidity of the world, but the Spanish government does not control that institution. The liquidity crisis, if strong enough, can force the Spanish government into default. Financial markets know this and will test the Spanish government when budget deficits deteriorate. Thus, in a monetary union, financial markets acquire tremendous power and can force any member country on its knees.

The situation of Spain is reminiscent of the situation of emerging economies that have to borrow in a foreign currency. These emerging economies face the same problem, i.e. they can suddenly be confronted with a “sudden stop” when capital inflows suddenly stop leading to a liquidity crisis.

… In the UK scenario we have seen that as investors sell the proceeds of their bond sales in the foreign exchange market, the national currency depreciates. This means that the UK economy is given a boost and that UK inflation increases. This mechanism is absent in the Spanish scenario. The proceeds of the bond sales in Spain leave the Spanish money market without changing any relative price.

Translation: For monetarily sovereign debtors, who issue fiat currency, with substantially all debt in their own money, the currency is the release valve. See my explanation here. For countries like Spain or Italy, when the bond vigilantes get a hold of them, money flees from Spain and Italy to Germany and the Netherlands, raising Spanish and Italian interest rates and lowering German and Dutch interest rates.

Even France can benefit from these flows, as has actually happened during the coronavirus pandemic.

My view

The spectre hanging over all of this is the potential breakup of the euro. Redenomination risk is the Black Swan risk for the common currency. Now, redenomination wouldn’t end those money flows between perceived weak euro sovereign debtors and perceived strong ones. But, it would mean that the release valve would go from the interest rate to the currency exchange rate. And, for the Germans and the Dutch, this would be a disaster.

That’s why the Germans and the Dutch may take a hard line on debt mutualisation now, but might cede ground once the talk turns to a breakup of the euro.

My concern for Italy is not about coronabonds or an imminent departure from the eurozone, but what happens after this crisis passes. We have already seen that back to back crises has both killed the Italian economy and pushed up government debt as a percentage of GDP. The two go hand in hand as a recession causes the double whammy of lower denominator (GDP) and higher numerator (debt), as transfer payments increase in recessions.

This crisis is no different; in fact, it’s actually more severe. We should expect GDP to fall further and debt to rise more. And the combination means Greek-like ratios for Italy when this crisis is over.

How does the ECB deal with that in ‘peacetime’? Do they continue to buy up Italian debt in amounts higher than Italy’s percentage of eurozone GDP? Are the Italians forced back into economy-crushing austerity to bring the debt down again.? What will the political fallout be?

Sure, the eurozone can muddle through this crisis with half measures. For example, there’s no need for coronabonds, if they can use the ESM. But, when the crisis is over, the euro’s problems will still be there. And we won’t be in ‘war’ mode anymore. There will be no exigent circumstances that mean fiscal rules are suspended and that the ECB can do whatever it wants. When peacetime returns to Europe, the rules will matter. And that’s when the trouble begins.

Comments are closed.