The big headline yesterday was ‘Tariff Man crushes markets’. But I think Donald Trump aka Tariff Man was more a proximate cause of market dislocation. The real worry is slowing global growth. Markets are closed today. So, it’s a good opportunity to take a breath and explain what I am seeing in the context of yesterday’s news.

Tariff Man

Let’s look at proximate cause of the market meltdown here. Almost 24 hours ago now, Trump made a series of four tweets explaining how he saw the temporary China-US truce. Here’s the most inflammatory one.

….I am a Tariff Man. When people or countries come in to raid the great wealth of our Nation, I want them to pay for the privilege of doing so. It will always be the best way to max out our economic power. We are right now taking in $billions in Tariffs. MAKE AMERICA RICH AGAIN

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 4, 2018

I reckon Trump probably thought the tweets were innocuous enough. But, in the context of an amorphous, squishy deal that Trump’s aides were having a tough time explaining consistently, the markets fell apart.

If anything, Trump is a marketer and a showman. So, it was clear to people that Trump’s claims about China were marketing fluff and showmanship. Yet again, after reading the fine print, no one knew what Trump had negotiated — even as Trump had come out of the negotiation full of excitement and praise for what he had achieved. We’ve seen this repeatedly, most infamously with North Korea.

So, Monday’s relief rally was ripped to shreds. And people started to worry again about a global growth slowdown.

The Yield Curve

Adding to the angst surrounding Tariff Man’s non-deal deal was the yield curve inversion. US bond markets are closed today for a day of mourning for George H. W. Bush. But Treasuries ended yesterday with the 2-year yield at 2.799% slightly above the 5-year yield of 2.791%. And with the 3-year yield of 2.808% even further above the 5-year.

I think I’ve been relatively consistent in saying that an inverted yield curve is not a signal of impending doom. Rather, it is a signal that markets believe the Fed will be forced to pause and eventually cut rates to deal with a slowing economy. The larger the inversion both in terms of rates and in terms of maturity, the bigger the market signal of future economic slowing and rate reversal.

The scary thing for the markets is that Fed officials are still talking up the near-term economy. When asked yesterday about the risk that a curve inversion highlighted, New York Federal Reserve President John Williams said:

“When I step back a bit I’m still of the view that with the economy on a very strong path with a lot of momentum, especially with some of the fiscal … tailwinds and other factors, that further gradual increases over the next year or so still makes sense.”

This is basically what Quarles, Clarida and Powell have said in recent remarks. They pay lip service to downside risks and to market signals like yield curve inversion. But, ultimately they all stress that the near-term outlook is positive, and why that makes it appropriate to continue gradual rate hikes.

Europe is not doing well

When you look at the global outlook, it is not coming up roses though. The receding yield on the benchmark German 10-year Bund is a market signal for distress. As I write this, it is quoted at just 27.3 basis points. And that’s off session lows of around 25 basis points. A month ago, the 10-year Bund was trading at 45 basis points.

The situation in Italy is a clear indication of why there is this flight to safety in Europe. Figures have been released recently, showing the Italian economy falling 0.1% q-o-q in Q3. And Bloomberg says that, with survey data showing weakness continuing into Q4, recession is a clear risk. It would be the first in 5 years.

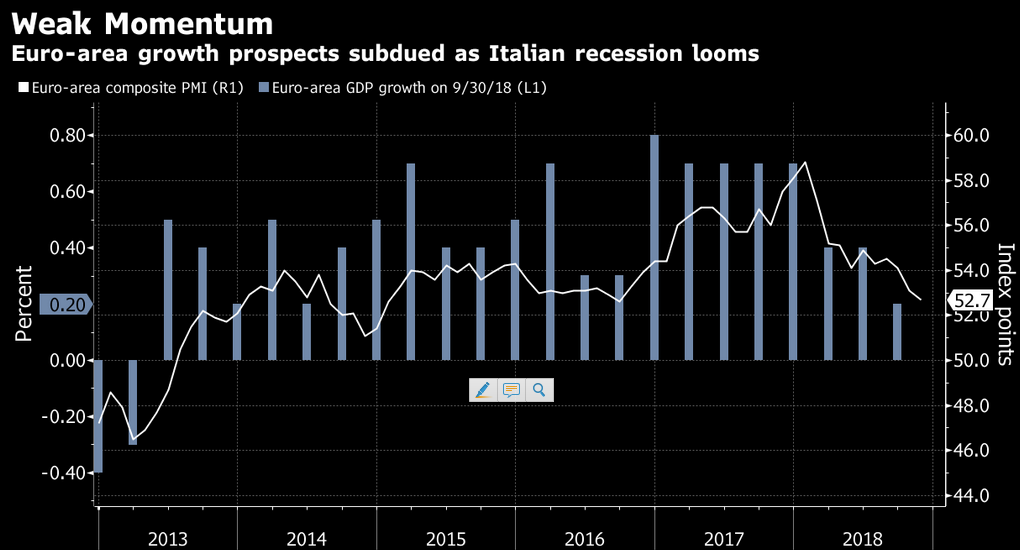

Overall, the euro area’s growth is weak as well. Remember that late in 2017, the eurozone was growing at 3.6% for a short while. That was 2.4% above trend. But, in November we learned that the euro area growth rate was a lacklustre 0.2% in the last quarter, with Germany contracting 0.2% outright. Just recently, the composite PMI fell to 52.7 in November from 53.1 in October. That’s the weakest level in more than two years.

Europe is not going to be a locomotive of global growth. The reason: Europe’s macro policy is completely export-led. Domestic demand has been sacrificed for export-led growth. And as the global economy slows, so too do exports. Germany is feeling the worst of it, as a result.

What about Asia?

Now, I already gave you a sense of what was happening in Asia with the PMI data that I pointed to on Monday. But, the key here is China. One of the reasons that the markets threw a fit when it turned out the China-US truce was a lot of hot air is because China needs growth. And the world needs China’s growth.

If we do eventually get the new round of tariffs that Trump had threatened to impose on Jan 1st , but that the deal delays, the hit to Chinese growth in 2019 would be as much as 1.0 – 1.5%. And that won’t be made up very easily by stimulus.

With fears mounting that the trade war will continue, China remains a major downside risk to global growth. The latest nowcast from Gavyn Davies’ Fulcrum Asset Management has fallen to 5.2%. That’s significantly lower than their forecast earlier in the year. And this loss of dynamism radiates out throughout Asia via China’s supply chains and regional importance.

Two other wildcards: First Russia

I want to close out with two economies which are also showing stress that we should keep an eye on. The first is Russia.

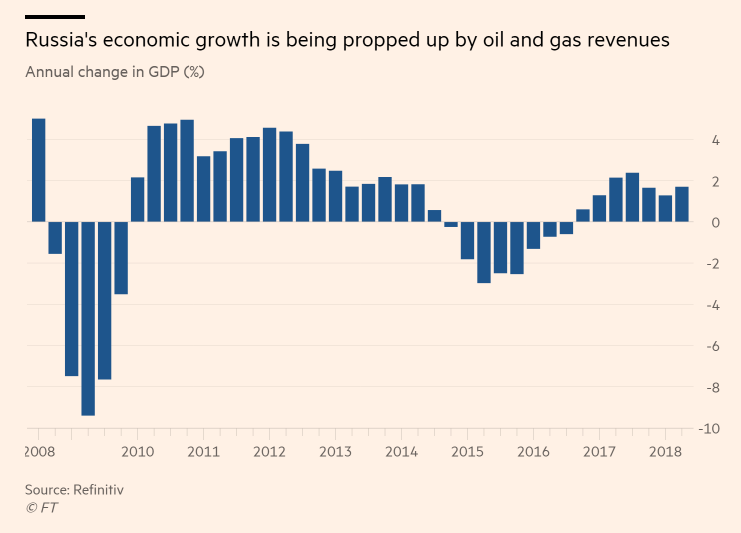

Oil prices have recovered smartly from the first shale bust in 2014 that crushed Russian economic growth.

And that has meant sanctions against Russia in the wake of the 2014 annexation of Crimea have not had as deep an impact. But, with crude prices now falling again, Russia will be in some considerable pain.

And that has meant sanctions against Russia in the wake of the 2014 annexation of Crimea have not had as deep an impact. But, with crude prices now falling again, Russia will be in some considerable pain.

Shale oil is the key here. Energy Information Administration data last month showed monthly US crude oil production had surpassed 11 million barrels per day for the first time ever in August of this year. We know this is all due to shale oil. But to give you a sense of the magnitude of the shale revolution, note that the volume of production today is more than double the level of crude oil produced by the U.S. in 2008.

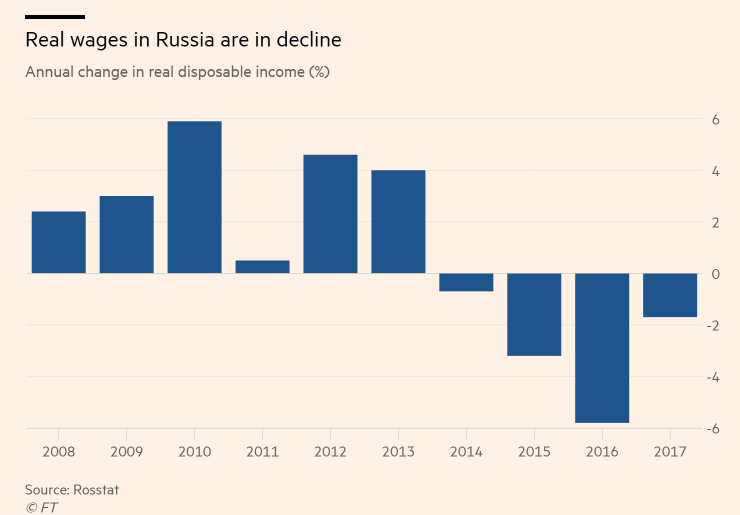

Without shale oil, crude prices would be much, much higher than they are today. And that’s a big problem for the Russians since their entire economy is being propped up by oil and gas revenue. I’ll leave you with this chart from the FT on the drop in real wages in Russia. That’s the vulnerability.

But read the full FT article. It gives you a sense of how dependent Russia is on oil and gas. And note this about Putin: “A poll this month by the Levada Centre, Russia’s independent pollster, showed 61 per cent of Russians hold the president personally responsible for the country’s problems. ”

The other wildcard: Australia

This comes directly from Steve Keen:

At the behest of the banks themselves, the Australian Parliament established a “Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry“, which has just concluded after a year of hearings…

The Royal Commission uncovered numerous instances of fraud, from charges for financial advice to dead people at one extreme, to pressure-selling of funeral insurance to young indigenous people at the other. But the fraud that undoubtedly did most to sustain the housing bubble was the pretense that borrowers were only spending just above the official poverty line, and therefore could devote their net income above a poverty level of expenditure to servicing their mortgages…

The banks helped keep those house prices rising by also aggressively marketing what they described as “interest only” home loans. In reality, these gave a 5-year holiday from principal repayments, after which principal had to be paid down to zero over the last 20 years of a 25 year loan. Monthly payments could increase by as much as 40% when the “interest only” period ended, but banks and borrowers assumed that would never be a problem, because by then the house would have been sold for a profit on that rising market. At their peak, “interest only” loans accounted for fully 40% of new mortgages

Those of you from the US reading this will find what Steve writes familiar, since a lot of this happened in the US too. The full article is available to subscribers of Steve’s at Patreon. So go to this link to read the full gory details.

What I would say here is that a banking crisis is not out of the question. Let’s remember that Australia has been integrally linked to China as China has grown in size and importance. And that has helped sustain Australia in the face of economic misfortune elsewhere, despite the huge housing bubble there. But now, Australia is uniquely vulnerable to a house price collapse, especially since prices are already falling. And that will make Ponzi borrowers vulnerable.

My take

The message here has to be that the global growth slowdown is actually accelerating. And I am certainly not convinced the US will escape the contagion. Moreover, in the US, you have two or three unique things happening as well. They include active monetary policy tightening, passive fiscal policy tightening and yield curve inversion.

The US is not going to be the engine of global growth here. With Europe, focused on exporting its way to growth and China both slowing and in jeopardy of tariffs, we have the makings of difficult times in 2019. For me, this is the message the bond markets are sending. And so, despite the near-term positive economic outlook in the US, it will pay to remain cautious.

Comments are closed.