The US Armageddon Scenario Part 2

The last post was an attempt to describe a reasonable worse case scenario for the US real economy as relatively benign compared to 1937, a comparison making the rounds these days due to a piece by Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio. My point is that 1937 is not a good comparison to 2015 in terms of the severity of possible real economy outcomes. Better comparisons are 1997 Japan or 1994 America. But on the other hand, in terms of market outcomes, I believe the severity of a potential decline is large. Some thoughts below

First let’s use some comments that I generally agree with from a reader who is a hedge fund manager as a jumping off point.

I thought Dalio’s paper was transparent book-talking, in an attempt to influence the Fed’s thinking going forward. And a really bad paper, to boot. The beautiful deleveraging seems like a fiction to me, invented I’m not quite sure why. On an economy-wide basis, you need a micrometer to measure it; it’s been pretty insignificant. And Doug Noland pointed out some time ago, I think correctly, that with regard to the financial sector, which is the one area where you do see some pretty significant deleveraging relative to the pre-crisis top—I just quickly checked and Goldman is 10x levered; they were 30x at the top, though I’m doing that without checking how solid their assets are, or the valuations—but Noland suggests that you need to include the Fed’s balance sheet to understand how much levered money is in the system, and I think that’s fair.

Then, the comparison to 1937 seems completely artificial. Dalio notes that the market was up four times from the bottom at that point, suggesting a very bubbly recover relative to our rather meager in comparison 2.5 times, or whatever it is. But It strikes me that might be a function of how far the market fell then, compared to ours six years ago. If instead we see where the market stands relative to the top before the crisis, you get a completely different picture; in 1937 it was still something like cut in half from pre-crash levels, while we are now miles above the October 2007 highs. And although I think our unemployment rate is a rather unreliable mirror to the state of the economy, we are nonetheless by standard measures pushing pretty hard against “full employment”, while in 1937 we were still well into double figures.

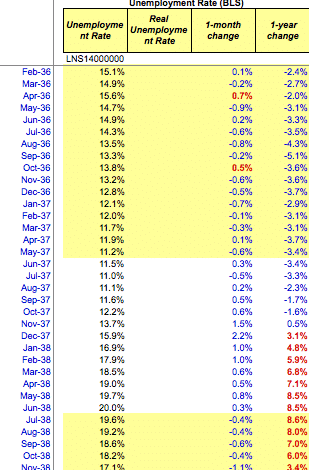

I looked back at the figures for the 1930s while I was writing the first post and considered mentioning that unemployment never fell below 10% in the 1930s. Here’s the relevant period.

So I wrote, “Let’s remember that the U-3 level of unemployment in the United States today is 5.5%. We would need to see a large 2008-style financial crisis, a terrific deleveraging and an economic bust to create a 1937-style economic relapse.” The reference point is the graph above. And while one could try to use the U-6 number as a comparison point for 1937, I see that as artificial. It’s clear that the economic starting point today is better than it was in the 1930s.

The reader makes some other good points on the Fed:

As it happens, I agree that a tightening Fed—and understand, we’re only talking about 50 or 75 bps here, when the average federal funds rate for the last umpteen years has been over 5%—will hurt the real economy. But the transmission mechanism for administering that hurt will be primarily from asset markets that get crunched. I think the wealth effect from the rising stock market has turned out to be cruelly assymetrical—very little from the increased wealth of the rising market, but a falling/crashing market will have enormous negative implications for the household view of the state of the economy, and spending will retrench a great deal. And then, of course, there’s also the King Dollar problem, and what that portends for all the dollar-denominated mostly emerging market debt, and also for US multinational profitability. But that’s really another issue.

But getting back to Dalio and the risk parity trade, there are widely available trades right now where you pay a premium of maybe 12%, which is what you’ve got at risk, and where you get paid 7-10 times that if two conditions are met: S&P below a certain number—the ones I’ve heard are around 2000, and shorter term, say 5 year, Treasuries above a certain rate, 2.1% or so, some time in the next two or three years. That speaks to the complacency that exists about the possibility of the Fed tightening here, and it’s hard to believe that Bridgewater and other risk parity trades are not positioned based on beliefs that are similar to the seller of that trade. And they’ll get killed if those conditions are met. Hence, as I see it, Dalio’s paper. BTW, note that Bridgewater guards its IP about as carefully as anybody out there; their papers are generally very hard to get your hands on. Yet this one suddenly appears courtesy of the FT? As I said, I think it was a transparent attempt to influence Fed thinking and actions, based on their portfolio positioning.

I don’t see the real economy as the primary path through which monetary policy has been transmitting stimulus. The portfolio balance path is very important here as investors have shifted en masse into higher yielding and higher risk assets due to the low nominal yield and negative real yield environment. And so as the Fed raises rates, that is the area through which I would expect ‘reverse transmission’ to occur, particularly because risk markets are not fully appreciating that the fed is serious about hiking rates. Just today, Reuters quoted Fed President Jeffrey Lacker as saying June would be the right time to raise rates – this despite weak consumer demand numbers in the latest monthly data set yesterday. I will have more on this later. But it is clear to me that the Fed wants to hike rates and that it is looking through present data right now in making a decision. If the March through May employment data take us down to 5.2% unemployment, a rate hike will happen this summer, as early as June.

The reader doesn’t think rate rises are going to be good either but for different reasons than Dalio, who presumably is worried about the market.

BTW, I don’t think the Fed can raise rates here, but for entirely negative reasons. They can’t say it, but they’re deathly afraid of King Dollar—I have to believe they understand the negative ramifications for our economy of the blowback from the emerging markets. And the regional presidents must be getting daily calls from the multinational CEOS as well. And Janet Yellen clearly understands the secular stagnation thesis, and buys it. During her speech Friday afternoon, the smartest rates investor I know messaged me that she’d just named Larry Summers Fed chair. So in spite of her upbeat characterizations during things like Humphrey Hawkins, I suspect she’s well aware that the economy is pretty fragile. And lastly, there’s that stock market.

I am not sure how afraid the Fed is of King Dollar but it certainly should be. And the reasonable worst case scenario I wrote about yesterday is a direct result of King Dollar’s appreciation. As a reminder, the scenario goes like this:

- The United States Federal Reserve raises interest rates due to the U-3 unemployment level falling to its 5.0 – 5.2% threshold/trigger range because inflation has not declined enough to prevent normalization.

- The US dollar rises in value due to the market’s reassessment of the prospects for further tightening in the US.

- The strong US dollar causes a downturn in oil prices that creates another wave of problems in the shale sector, lowering capital expenditure and creating job losses, knocking tenths of a percent off of GDP growth. Contagion spills over into the high yield market.

- At the same time, the strong dollar becomes toxic for emerging market debtors with significant US dollar liabilities in countries like Brazil and Malaysia. This causes an emerging markets crisis.

- In China, where the growth in credit has not been as successful in maintaining GDP growth, the economy continues to slow despite monetary and fiscal stimulus. As a result, economies dependent on China for exports like Australia and Brazil are caught up in more problems.

- Brazil becomes a focal point of the emerging markets crisis due to its dependency on a slowing China, on oil for tax revenue, and on the US dollar market for debt. But the contagion in EM is everywhere.

Fed tightening is a problem first and foremost because every other central bank is easing. Even Canada and Australia are in easing mode. And I expect New Zealand to join. That makes the world’s reserve currency expensive in relative terms, something that is a big problem since both creditors and debtors outside of the US also use US dollars for credit transactions as their central banks accumulate foreign reserves. Brazil is a focal point for the reasons I gave above. But there are plenty of other countries where private debtors are loaded up with US dollar-denominated debt that can serve as a point of contagion to other parts of the economy where financial fragility is high due to high levels of leverage.

Where I agree with Dalio is that we are at the extreme edge of monetary policy effectiveness, meaning that we are literally one cyclical downturn away from entrenched deflation. Japan is already there. Arguably, Europe is there now as well. So Fed tightening is also a problem because of leverage in the US economy. Despite the apparent deleveraging in the household and banking sectors in the US, aggregate private debt levels remain high compared to levels over the rest of the debt supercycle. I would expect a reasonable degree of deleveraging if the US hits a rough patch in the real economy. Again, I am not talking about 1937 here, but 1997 Japan. the reason 1997 Japan makes sense as a comparison rather than 1937 is the severity of the initial downturn is comparable and other attenuating issues like demographics are also comparable. Poor demographics mean a lack of aggregate demand to boost nominal GDP enough to do the deleveraging via economic growth. Debt to GDP levels have remained comparatively elevated such that debt stress will remain in place at the next cyclical downturn. This is true today as it was in 1997 Japan. And all we need at this point is a policy error to entrench deflation.

What kind of policy errors am I talking about? Clearly a combined monetary and fiscal tightening is what we will need to see. In Europe, the deficit hawks have taken control and are forcing a fiscal control that tends to reinforce deflationary (and debt deflationary) pressures. I believe the last downturn in Europe put it in a permanent Japanese situation given the poor demographics there. In the US, if we had deficit hawks take control at the White House and in Congress, the stage would be set for the kind of policy error which, combined with monetary tightening, could throw the US into recession and begin the deflationary period that Japan and Europe are already in. If the Republicans gan the White House in 2016, this is an outcome that has a reasonable chance of occurring.

But on the market score, we are already 3x the S&P’s 666, at NASDAQ 5000, and at CAPE levels that are associated with market tops. Moreover, all of the anecdotal evidence from the technology sector speaks to another technology bubble and the high yield market is still elevated despite the initial shale oil jitters. Fed tightening will change this. Yellen says the Fed will be cautious and is trying to act as if a ‘one and done’ type of dynamic is in the cards, where the Fed reassesses after an initial hike. But I still believe the chance of market dislocation is large and that the downside risk is also large given where we are in the economic cycle. I believe we are still in a secular bear market and this means that cyclical bears are especially savage as they combine the real and operating leverage reversal with earnings multiple declines to take 30-50% off of frothy markets. The Armageddon scenario for markets is a lot worse than it is for the real economy.

Comments are closed.