Will the Fed(s) stay the course?

This post on the bond vigilantes is inspired in part by my friend Kevin Muir and a post he just did over at The Macro Tourist. It’s also inspired by the inflation numbers that came out of the US earlier today. The question to answer: how will the bond vigilantes respond? And what will the Fed(s) do?

Americans paid not to work

Let me start with an addendum to the last post because that post was also about a mooted economic policy paradigm shift and whether the Feds will stay the course. There, the macro question was “how long past the cycle trough governments use fiscal policy”. And we’ve been handed this question with unemployment benefits in the US. A lot of people are crying out to reduce those benefits to incentivize workers to take up (low-wage) employment. And so, this is the first test as to whether there has been a wholesale change in the willingness of government to use fiscal policy outside of business cycle troughs.

But, I want to mention that the US model of completely separating workers from their employment during downturns isn’t the only possible flexible employment model to employ. In Europe, the German model of Kurzarbeit is attracting attention:

Referred to by some economists as one of Germany’s most successful exports, Kurzarbeit, the short-time work benefit, is a scheme which came into its own during the global financial crisis of 2008-9 when it brought stability to the country’s labour market. Germany was the only G7 economy to avoid a rise in joblessness in 2009 and Kurzarbeit receives much of the credit for that achievement.

But the policy’s history goes back much further, to approximately 1910, when it was first introduced as a way of tackling a capacity cutback in the potassium salt industry. Affected workers received a Kurzarbeiterfürsorge, or “short-time work welfare”, payment from the German empire.

It has subsequently been most typically used to help overcome short-term problems such as flood damage or bad weather impacting the construction industry.

[…]

Effectively a social insurance programme, and an alternative to redundancy, under Kurzarbeit, employers reduce their employees’ working hours instead of laying them off. A large portion of the workers’ lost income is picked up by the state.

So for the hours not worked, an employee initially receives 60% of their wage, (67% for parents) and is fully paid for the actual hours worked. For a 30% reduction in working time, the loss in salary terms is only 10%.

Adjusted to deal with the prolonged nature of the pandemic, during the fourth month the rate increases to 70%, and to 80% from the seventh month.

Now imagine four workers, two in Germany and two in the US. In the US model, the one worker is working full time and the other is receiving unemployment insurance during the pandemic. In Germany, one is working full time and one is working under the Kurzarbeit work program. How easy will it be for the second employee in both models to ramp up to their previous level of work salary?

I would argue the German employee has more options and greater chance of getting a full salary. They can resume full-time at their present employer or find another job, all while still being employed. The American worker, by contrast, is unemployed and losing perceived employability. They might be able to return to their previous employer. But then again, maybe not. They can also work elsewhere, but “it’s always better to get a job when you have a job,” as they say.

For now, the US is forging ahead because of vaccination, leaving Germany in the dust economically. It will be interesting to see how this difference in unemployment schemes manifests itself via growth and employment further into the pandemic recovery.

The inflation bogeyman

For now though, it’s inflation that has everyone mesmerized, particularly in the US, where growth is accelerating. Here’s how my colleague Jack Farley put it:

Inflation numbers blowing past expectations, leaving every single economist estimate in the dust

4.2% year-over-year change in the CPI vs. 3.6% median estimate.

Highest estimate was 3.9% (of the 47 I found on Bloomberg) pic.twitter.com/gGhlF0z4Hg

— Jack Farley (@JackFarley96) May 12, 2021

How do the bond vigilantes react? How does the Fed react?

Before the report came out, I was saying the bond vigilantes weren’t done.

By the way, I still think rates are the ‘toggle’ for the present investing climate and that the bond vigilantes will have more runs at steepening the curve.

If so, it will have a big impact on discounted cash flow models – even if you think valuation has changed https://t.co/riM5nVjNbq

— Edward Harrison (@edwardnh) May 12, 2021

And sure enough, they sent 10-year yields up to 1.68%, causing the tech-heavy Nasdaq to implode by 2%.

It’s the DCF, stupid! as they say.

What’s going on here? CPI was at 2.6% year-on-year through March. And because last year’s lockdowns were deflationary, economists expected the return to normalcy to make that number rise to 3.6% y-oy. Instead it rose even more than expected to 4.2%. And that’s not good if you think the Fed will eventually react by tightening policy.

Sure, the Fed gets a bit of a free pass now. But 4.2% is a big number. And, at the margin, higher than expectedly high inflation numbers will lead to people thinking the Fed will tighten.

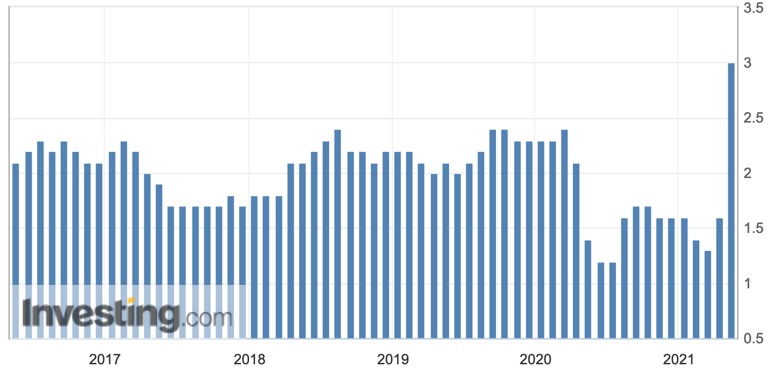

Core CPI was 3.0% too. That’s up from 1.6% and ahead of expectations for 2.3%. Notice how that number stands heads and shoulders above previous data points.

You have to go all the way back to 1995 to find a number this high.

The Bond Vigilantes

So, it makes sense that, at the margin, investors have started to question the Fed’s resolve on holding firm on monetary accommodation, given how much inflation has jumped. This means higher long-term rates because a large swathe of bond investors now believe the Fed will move up its timetable for tightening, so large is the inflation wave.

This is the how bond vigilantes work. Their role is to test the resolve of the Fed – test the Fed’s adherence to its policy guidance. Is the Fed so wedded to the concept of full employment that it’s willing to completely disregard its inflation mandate? How much does inflation have to rise before the Fed changes its tune about inflation’s being transitory? And if the Fed changes tack, what will they do? Those are the questions bond vigilantes ask. And they express them through buying and selling Treasury securities. The uptick in rates begins at the 2-year rate and increases the most at the 7-year rate, with the 10- and 30-year bond yields increasing somewhat less. So, at the margin, the bond market is saying that the Fed is likely to accelerate its timetable for withdrawing monetary accommodation in the medium-term. And that’s having a negative impact on rates, with the impact most pronounced on 7-year Treasuries.

That’s all fine and good. But this only matters if the Fed changes tack or if inflation expectations become so unanchored that it breaks the market. It’s the breaking the market part of things we should be thinking about because that’s where the bond vigilantes have sway.

In one scenario, the Fed can just refuse to budge and bend the bond market to its will. But, that only works 100% effectively at the short-end of the curve. At the longer end of the yield curve, expectations can carry the market past where the Fed wants it. In 2018, when the Fed was tightening, we saw this. And the end result was a tightening in financial conditions that was so severe it forced the Fed into a retreat. That’s where we need to be cautious.

The reality is that the US Treasury curve isn’t nearly as steep as it has been when prior economic cycles have begun. The bond vigilantes could send inflation expectations and long-term rates way up from here. Think 10-year rates at 2.25%, for example. How much are you willing to pay for Tesla at that discount rate? How about TripAdvisor or Applied Materials? It certainly depends on whether you think there’s another recession in the next 5 years. You also have to ask yourself what mortgage rates look like since housing’s a sector that has been red hot. And it has arguably helped boost economic momentum in the US economy.

My View

All of this is at play right now. So I think the markets have moved on from the Reopening Trade and are now thinking about what happens after the re-opening. A big part of that is what the Fed does. A big part of that is what kind of sustained fiscal response we have. And another big part of that is about post-pandemic consumer behavior since signs of altered behaviors are everywhere.

I would argue the risk has shifted again from upside risk, back to downside risk. The overshoot on inflation and undershoot on employment in the US tells you that. Moreover, equities are still very much vulnerable to discounted cash flow valuations. Don’t believe it when people tell you otherwise. This is still the only reliable way we have of thinking of valuation – future cash flows discounted back at some rate to present value terms.

We can be optimistic about an individual businesses opportunity set and likely future free cash flow generation. And that will be reflected in the price. But at some point, as in the late 1990s, animal spirits can force valuation to become divorced from all but the most optimistic future realities. Think of the share price of Tesla as a call option on assorted future realities. Some of those realities have Tesla dominating multiple businesses due to ever-increasing network effects. Some of those have Tesla faltering under the onslaught of competition from auto manufacturers in its main business model.

It’s like predicting in 1999 whether Amazon would rise to be an e-Commerce juggernaut across the globe or be beaten back by Borders and Barnes & Noble in the United States. There are a wide dispersion of outcomes. And the central tendency of the probabilities of those outcomes gives you the valuation of your call option. Cathie Wood and her people at Ark Invest have been saying that central tendency of future free cash flow scenarios is high. Let’s see.

However you look at it though, the Coming to Jesus moment for inflationistas and pent-up demanders alike is right around the corner. And so, the full re-opening will usher in a much better understanding of where we’re headed. There are likely to be serious surprises in asset market valuations.

Comments are closed.