The German view of the Euro crisis

The Germans got into the eurozone out of a desire to increase European integration and to strengthen Europe as an economic area that rivalled the United States. Yet, now we are in a period where the Germans are being blamed for everything that’s going wrong with the Euro. I think the Germans do deserve some of this blame but not all of it and I want to briefly post why. Consider this an addendum to the other Edward’s piece that was posted just before this one, but from my own somewhat pro-German point of view.

I had lunch in DC on Friday with my good friend Rashique Rahman who is the EM strategist at Morgan Stanley. He was in town for the Annual IIF meeting and had a break in his schedule. And we had a good chat about emerging markets and private portfolio preferences in this zero rate environment. He mentioned to me that he missed the really good panel discussion with Axel Weber, chairman of UBS, Stephen King, chief economist at HSBC, Willem Buiter, chief economist at Citigroup, and Stephanie Flanders, chief market strategist for U.K. and Europe at JPMorgan Chase. So I looked for the video, watched it and sent it to him. What struck me about the discussion was the difference between what Willem Buiter had to say and what Axel Weber had to say. And I think their diverging views encapsulated the problems in Europe that are getting the Germans blamed for the Eurozone’s woes.

Now, in my post on the weakness in the German model on Friday, I got into some of what Weber was saying and the weaknesses in that point of view. But the IIF video and Edward Hugh’s piece made me want to revisit this topic.

As I outlined on Friday, the primary goal of the German model is to minimize debt as a potential catalyst for crisis. The Germans had a massive undertaking in reunifying the country twenty years ago and did quite well to integrate East Germany into the West without increasing private or public debt levels or severely crippling the social safety net. Having said that, Germany has been in technical violation of the Maastricht Treaty for years now. And with unfavourable demographics, the country faces a difficult battle to retain growth necessary to support their social safety net while keeping debt burdens low. But the goal is to keep debt low, by hook or by crook. And if that means suppressing wages, relying on exports or making the social safety net less secure, then I believe the Germans will make the compromises.

It is this adherence to a low debt paradigm that I see as paramount in German thinking rather than the anti-inflation bias that is ascribed to the Germans. For example, as much as the Eurozone wants stimulus from Germany, the fact is Germany is concerned about its own public finances. The country is well over the 60% Maastricht debt hurdle and it has to contend with an aging society that will draw more on public finances while still trying to keep benefits high. One example here is that the SPD forced the CDU into backtracking on its desire to raise the retirement age as part of its grand coalition demands. In this context, Wolfgang Schäuble’s seeming public debt and deficit fetishism makes a bit more sense. It is driven by a sense of unease and insecurity about public finances in a country where discipline and order are praiseworthy.

So what I see people like Weber saying is that so-called Keynesian approaches to the sovereign debt crisis are only temporary solutions and should be used in sparing measure, only to prevent crisis. His view is that the road to riches over the longer term is paved with structural reform and fiscal discipline. Looking at an extreme version of this view, let’s look at Ifo Institute Chief Hans-Werner Sinn’s comments.

Sinn believes the Eurozone must become a full fiscal union, a United States of Europe, in order to work. He believes that the Eurozone as structured now is just a “debt union” or “Schuldenunion”. In this view, German banks unwisely financed current account deficits in the periphery. And when the periphery ran into trouble, the German political elite allowed Zombie banks to remain alive for fear of what recognizing bad debt losses would do to the European and German financial system, not to mention the political and social system. The ECB was very instrumental in this process because it lowered rates to zero percent and has supplied cheap financing to banks with insufficient capital. As a result, Sinn says that the periphery is now almost incapable of carrying through with structural reform.

Much of this is true. And the comments that SInn makes are echoed by Axel Weber, former ECB Chief Economist Jürgen Stark and present Bundesbank head Jens Weidmann. Through the end of 2013, Angela Merkel had sided with SPD man Jörg Asmussen, who was her liaison to the ECB, in an intellectual spat with the likes of Stark and Weber. They resigned but Asmussen’s presence blunted the impact of those resignations. Asmussen is now gone and so the pressure for Mario Draghi to listen to Weidmann’s concerns are increased as there are no countervailing German voices on monetary policy.

The Sinn view, as expressed in his new book, “Gefangen im Euro” or “Trapped in the Euro”, is that Europe could go through two lost decades like Japan, if it continues down the present path. Once the periphery moves to a reform-oriented approach, labor costs will come down and productivity will increase. And this will set the stage for a complete and real political and economic union. But that will is lacking at the moment.

This all makes a lot of sense, especially as Germany did exactly this in the 2000s. And many say Sweden also used this reform model to great success. The problem is that it is politically not feasible across a wide swathe of countries given the economic start point. You can’t suppress wages and prices without the economy contracting, taking on more debt and causing the real burden of existing debt to rise. In Italy, for example, this approach would see government debt to GDP soar to 160% by the end of the decade, without any promise of the nominal GDP growth necessary to bring that debt down again. One more recession or crisis would take Italian debt to Greek levels and mean debt default.

Now Sinn knows that debt default is necessary and actively advises the periphery to admit this. But this is not politically feasible. Nor is it without tremendous risk. I suspect Sinn understands this. But, on some level, he is unwilling to live in a debt union and would rather see the politics force the Euro apart. This is why the AfD party in Germany has won converts. It is essentially an anti-Euro party, not because the party is anti-European but because they believe the Euro cannot succeed on terms that Germany should be willing to accept.

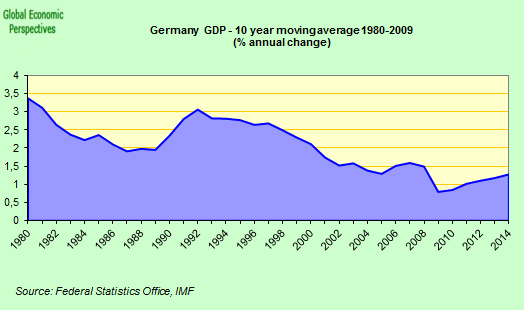

In the IIF debate, Buiter talked about structural reform as well and Weber highlighted the agreement there. Nevertheless, I got the sense that Buiter understood that the Euro integration terms which Weber was pushing had no basis in political reality outside of Germany. Moreover, even Germany is showing economic weakness due to exports and demographics. And these are structural weaknesses as Edward Hugh pointed out in his chart of the declining economic growth rate for Germany.

As an analyst I watch this debate and see a situation where it is clear that there is not enough consensus to move to a political and economic paradigm which will stop the decline in both inflation and nominal GDP in Europe. For me, Europe seems locked into a trajectory which guarantees another crisis at some point down the line. And while the OMT maneuver has allowed periphery sovereign yields to fall, crisis will mean sovereign yield decoupling that ends in defaults, eurozone breakup, and/or much more explicit ECB sovereign backstops.Only then could we see a new consensus economic and political paradigm for Europe. Until then, Europe will remain weak and will continue to underperform.

Comments are closed.