Some thoughts on easy money and fiscal withdrawal

Today’s commentary

Brief comments outside the paywall today.

In the links today, I had a number of good posts that focused on the issue of fiscal policy versus monetary policy. There are a number of ways to look at the issue, economically and politically. However, I think the overriding takeaway politically is that fiscal policy will remain constrained irrespective of growth. Monetary policy will be used if growth undershoots. This will have consequences.

But before we get into what the consequences of over-reliance on monetary policy are, let’s just review the narrative that is developing. David Beckworth makes the argument in support of the market monetarist view which has gained momentum. He writes:

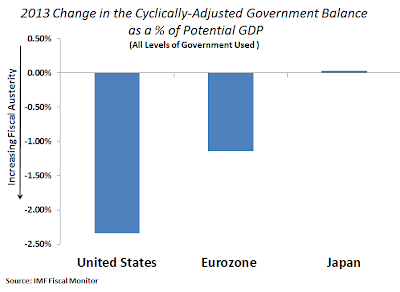

I put together the following figure using the latest IMF Fiscal Monitor. It shows the 2013 changes in fiscal policy for the three largest advanced economies. A negative number means fiscal policy tightened, while a positive one means it was expansionary:

This figure is striking. It shows that in 2013 the sharpest change in fiscal austerity was in the United States.

Now let us put this all together. The Fed QE3 program was pitted against the sharpest change in fiscal austerity across the largest advanced economies. Many observers predicted this fiscal austerity would lead to a recession. Other predicted it might costs as many as 700,000 jobs. Market monetarists like Scott Sumner and myself were more optimistic.

I think fiscalists will have a hard time counteracting that narrative, frankly. The reality is that we have seen the tightening fiscal – loose monetary policy combination produce higher growth rates in the United States and the United Kingdom than most anyone expected. And this comes with fiscal deficits in the US receding at the fastest rate in 60 years. So, one can’t just come out and say easy money doesn’t work. It does work. The question goes to unintended consequences like bubbles.

Larry Summers gets at this in the FT by making his thinking plain about secular stagnation and bubbles. He sees repeated bubbles from an asset-based economic model as a problem, not an optimal solution.

So the secular stagnation challenge is not just to achieve reasonable growth but to do so in a financially sustainable way. There are, essentially, three approaches…

[…]

The second strategy, which has dominated US policy in recent years, is lowering relevant interest rates and capital costs as much as possible and relying on regulatory policies to assure financial stability. The economy is far healthier now than it would have been in the absence of these measures. But a strategy that relies on interest rates significantly below growth rates for long periods of time virtually guarantees the emergence of substantial bubbles and dangerous build-ups in leverage. The idea that regulation can allow the growth benefits of easy credit to come without the costs is a chimera. It is precisely the increases in asset values and increased ability to borrow that stimulate the economy that are the proper concern of prudential regulation.

The third approach – and the one that holds most promise – is a commitment to raising the level of demand at any given level of interest rates, through policies that restore a situation where reasonable growth and reasonable interest rates can coincide.

So what Summers is saying is, “yes, the monetary policy-dominant approach can boost growth but it leads to build-ups in debt and to financial fragility. And that is destabilizing economically.” This is a good counterpoint on what I call the limits of monetary policy.

The thinking at the beginning of 2013 was that this combination of receding fiscal stimulus and loose monetary policy would continue to produce weak growth. If the US had gone fully over the fiscal cliff, I believed it would mean recession. But that is not what has happened. Why?

I would say it goes to asset prices and deleveraging. Until 2013, the rise in asset prices was not enough to overcome the need for and psychology of deleveraging. This was particularly important regarding house prices, a leveraged asset that constitutes the bulk of most household’s net worth. The financial crisis put many households underwater on their housing investments. This led to an inability to refinance mortgages, a loss of mobility, mass defaults, and a general household deleveraging.

But in 2013, the US led the way in house price increases. That stopped deleveraging dead. Consumer credit is up, while debt service costs are at generation lows.

The fiscal withdrawal will continue into 2014 in order to push down deficits. In the US, unemployment benefits are being cut. In the UK, Chancellor George Osborne has warned that more cuts are coming. Where is this heading? Based on leading indicators, growth in the near term will be good. But wages are not rising yet, while household debt is. That leaves a murky legacy for this asset-based growth strategy.

Comments are closed.