The A-b-e of economics and Japan’s shrinking population trap

By Edward Hugh

And the world said “Let Shinzo Abe be”, and all was light.

“The point is not that I have an uncanny ability to be right; it’s that the other guys have an intense desire to be wrong. And they’ve achieved their goal.” Paul Krugman

A new craze is sweeping the planet. The image I have in mind isn’t exactly that of the community of central bankers all dancing the Harlem Shake in unison, but for all the economic sense it has it might as well be. In fact the craze is called “Abenomics” and it is gathering adepts in financial markets across the globe. A precursor in Japanese history has already been found for the movement, Korekiyo Takahashi, who was the country’s finance minister during the key years of the 1930s depression. Even a book has been written to extol his virtues entitled “From Foot Soldier to FinanceMinister: Takahashi Korekiyo, Japan’s Keynes.” Unsurprisingly it was an immediate hit with Japanese academics when it came out in 2010.

While the creation of the Takahashi lineage may be important for home consumption in order to make the Japanese themselves more comfortable with the adoption of a set of radical and even unprecedented measures – Japan isn’t exactly the country you would expect to be in the vanguard of a major economic experiment with extensive global implications – the resonance of Abenomics outside the country among those with little knowledge of economics and even less of the specificities of the Japan problem is perhaps rather more surprising. Mariano Rajoy, for example, told journalists recently that the recent BoJ decision represented a “very important change in its monetary policies.” The Spanish PM argued in a clear reference to what is going on in Japan that Europe needed to decide which kind of powers its central bank should have, those it has now or “the ones other central banks across the globe have”. “We are in a decisive moment,” he said.

Despite the fact Abe’s move fits comfortably on the austerity vs growth policy axis, at the heart of the new approach lies not a strategy to directly create growth per se, but rather one to try to induce inflation. The idea, which may have some understandably scratching their heads in confusion, is to see whether by this rather circuitous route it is possible to tease the country back on to what advocates of the policy consider would be a more normal growth trajectory of the kind from which it has been exiled for the best part of two decades now. The inflation-inducing monetary injection could be thought of as something like the kind of sharp jolt given to a twisted spine (or a dislocated shoulder) by the firm hand of an experienced osteopath. Once the shock has been administered, so the story goes, the patient should once more be able to walk – and develop – normally.

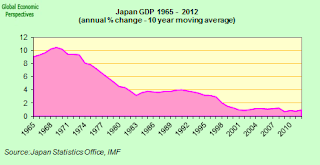

Naturally, the very existence of the this other, alternative, path for Japan remains at this point a mere theoretical postulate since with so many bouts of fiscal and monetary stimulus having been administered over the years, just exactly what a normal growth pattern would be for the country, or even what exactly “normal” means in this context, is at this point very difficult to discern. The fact that the population and workforce are now both ageing and shrinking in ways for which we have no historical precedent means that you wouldn’t necessarily expect to see that much growth in the economy anyway. Indeed, in order to make allowance for this new phenomenon some have started to claim that Japan is not doing so badly after all (or here), since GDP per capita has been performing tolerably well in comparison with the US or Europe, so in some ways it is hard to see what all the fuss is about, except… except….. except for that nasty, nagging little detail of all the government debt that has been being run up in the meanwhile.

For those who have not been following the Japan saga as it has developed over the last twenty odd years this whole debate may seem like a strange way of thinking about things, after all isn’t inflation supposed to be a bad thing, one central banks are supposed to combat? And how can a country become more competitive by force feeding inflation? The fact of the matter is, however, that during all that time the country and the Bank of Japan have been continually fighting and losing an ongoing battle with falling prices. And it is this battle with falling prices which means that the “tolerably good” economic performance becomes a serious problem, a serious debt problem.

Of course, falling prices are not necessarily in-and-of themselves a bad thing – as any old consumer will tell you -since products get cheaper and cheaper with each passing day. So the run of the mill consumer might find life in Japan quite a pleasing and desirable thing, especially if that particular consumer happens to be retired and living on a fixed income from savings as many contemporary Japanese actually are. Falling prices only really become a problem in a more general macroeconomic sense if they lead people to postpone consumption, and if this postponement becomes self perpetuating in a way which leads prices to continually fall, as the combination of constant productivity increases and stagnant demand produce perpetual oversupply. Falling prices also constitute a nasty headache for policymakers since while prices go down the value of accumulated debt doesn’t, and herein lies the rub. So additional “stimulus” which doesn’t lead to increasing nominal GDP simply pushes the sovereign debt even farther along an unsustainable trajectory.

The problem Japan has is one of a perpetual shortfall in domestic consumer demand and the core issue is whether this shortfall is simply being generated by consumption postponement, or whether there are deeper structural factors at work.

It’s The Demography Stupid!

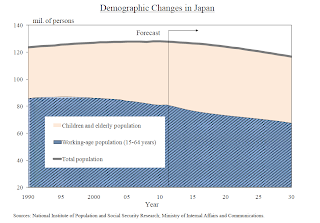

As everyone now recognizes and accepts Japan has a rapidly ageing population and an ageing and shrinking workforce. This situation, which has really been obvious for years has only lately come to be regarded as a significant component in the “Japan problem”. This neglect has most probably been due to the influence of a deep seated predisposition among adherents of neoclassical growth theory to think that population dynamics don’t fundamentally influence economic performance in the long run.

However, and as I think is now clear to all, one result of the “demographic transition” that is going on in Japan (and which will be replicated in one country after another as the century advances) is that while GDP per working Japanese continues to perform tolerably well, and, as I said, GDP per-capita growth bears comparison with many other countries in the developed world, government debt to GDP levels now bear no such comparison and have started to surge off the known register. Obviously something has to be done.

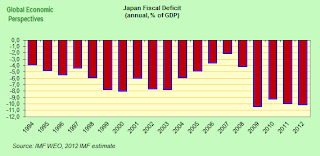

In 2012 Japan gross government debt stood at 235% of GDP and naturally with falling nominal GDP the burden of the debt would still continue to rise even if there were no further fiscal deficits. But fiscal deficits there are and there will continue to be since without such “stimulus” it is apparent that even real GDP would be perpetually negative. The country has been running a fiscal deficit of close to 10% annually and Shinzo Abe has promised even more fiscal stimulus in 2013 as one of his three key “economic arrows”.

You don’t have to be an economic or mathematical genius to see that this can’t simply go on and on. Japan has now passed some sort of tipping point. GDP per working Japanese may continue to rise nicely, but as the working population steadily shrinks a the 21st century advances then surely total GDP will eventually start to fall. If in addition prices continue to drop then government debt to GDP would start to rise almost asymptotically even without any more government borrowing. And naturally Japan is not a unique case, since during the course of the 20th century one country after another will be faced with the same sort of problems. That is why the country is now so important.

What is going on in Japan is a huge collective experiment on all our behalf’s. And we have also passed a tipping point in another sense, since if what Abe is doing doesn’t work there is now no realistic possibility of turning back. Relative prices and values across the whole global economy are currently being distorted to such an extent that any sudden loss of faith in the experiment would surely have consequences which reached far afield and far from benign. Austerity reins are now being loosened all over Southern Europe (a region where population ageing is not far behind Japan) and debt levels are surging. If Japan can’t pull it off then neither can Southern Europe, meaning all those bond yields which are coming down simply shouldn’t be doing so. Japan is simply the pioneer.

What Went Wrong In Japan?

Basically, in terms of our classical understanding of economic problems there are two straightforward solutions to the Japan debt problem: either the economy achieves more growth (which as we have seen will prove difficult given the shifting demographics) or it generates continuing inflation, since inflation pushes nominal GDP into positive territory and hence eases the scale of the debt burden. But, we need to ask ourselves, what if something important has changed and Japan now faces the worst of both worlds, getting virtually no growth while at the same time remaining stuck in deflation. While few are yet willing to contemplate either the possibility or the consequences of this eventuality this does not mean that it is an outcome which can’t happen.

But before examining that possibility a bit further, let’s dig a little deeper into the intellectual backdrop that lies behind Abenomics.

“Japan: what went wrong?” is the title of a 1998 article by Paul Krugman (you can find it on this site under “Japan”). Krugman’s work at this time has some significance for the current policy approach since in many ways he can rightly claim to be the intellectual father of the Japanese experiment. He was the first economist of note to see that something important was happening in the country, and the first to see that some sort of major initiative was going to be needed to address the emerging problems. In particular the whole idea of trying to correct the Japanese imbalance by targeting inflation can be traced, for good or ill, back to his door.

The “what went wrong” article is useful, since there he tried to set out in simple layman’s terms his version of the Japan story. For a number of reasons it is worth going back to these old arguments since they help make sense of recent events, and offer us the opportunity of glimpsing the initial justification for the Bank of Japan policy initiative that Mariano Rajoy and others find so interesting in all its full glory.

Krugman’s starting point is population ageing. The details could be changed, and the argument fleshed out a lot, but this is basically the picture he paints to explain why the country fell into deflation – the Japanese don’t spend more because, on aggregate, they are trying to hang onto their savings.

Here’s the story: Japan, like the United States only much more so, is an aging society. Thanks to a declining birth rate and negligible immigration, it faces a steady decline in its working-age population for at least the next several decades while retirees increase. Given this prospect, the country should save heavily to make provision for the future–and lacking the kind of pay-as-you-go Social Security system that allows Americans to ignore such realities, it does. But investment opportunities in Japan are limited, so that businesses will not invest all those savings even at a zero interest rate. And as anyone who has read John Maynard Keynes can tell you, when desired savings consistently exceed willing investment, the result is a permanent recession.

Actually more than saving, the problem is really that the Japanese won’t commit to borrowing (again on aggregate). Hence some people locate the problem as a monetary transmission mechanism one – the normal credit cycle simply won’t start because the economy is suffering the after-effects of a “balance sheet recession”.

But another approach to the problem would be to try and understand whether the failure of both Japanese households and corporates to harness themselves to what is considered to be a “normal” credit cycle might not be associated with the age structure of the country’s population. In fact the Japanese household saving rate has been falling steadily over recent years, and it is Japanese corporates who are doing the saving, but the latter won’t invest in the domestic market for the reason Krugman identified – the lack of consumer demand for end products – and indeed perhaps this reluctance is fortunate since with final demand limited more supply would only push prices down even further. The idea that further investment would in and off itself produce enough incremental demand to soak up the capacity expansion sounds very much like the Spanish housing and immigration story – Spain was, on this account, bringing in immigrants to build houses for which they themselves would be the customers. This kind of investment-lead demand simply doesn’t work, as we are also seeing in China.

Investment has to some extent to be driven by autonomous demand, if it isn’t imbalances are inevitably generated, even if, in a well-oiled economic machine the investment generated by that autonomous demand is what drives the business cycle forward. But in Japan this kind of demand-lead investment process isn’t working (outside the export sector) for reasons which have demographic roots and not due to malfunctioning of the monetary transmission mechanism. Thus the key difference between the world of contemporary Japan and the world Keynes contemplated is that the shortage of demand in his model was simply conjunctural (due to the presence of a liquidity trap) and not structural and permanent, as in the case of demographic decline.

Although one of his contemporaries, the Swedish Nobel prize winner Gunar Myrdal, did go into this demographic possibility (fertility in Sweden had already dipped below the 2.1 child per woman replacement level in the 1903s) and Keynes did read Myrdal’s Godkin Lectures where the ensuing process is examined, the author of the General Theory never really contemplated the kind of problem Japan is facing. This is a pity since it only really makes sense to use the expression “liquidity trap” if you are making the kind of assumption Keynes was – that there is some sort of “normality” (the normal credit cycle, for example) to return to, so that the damage that was being caused to the normal functioning of the economy could be put right by some kind of self-correcting mechanism. If what you are faced with is an economy that is becoming extremely dysfunctional following almost four decades of ultra-low fertility then it is not at all clear that this self-correcting solution is available. Hence Japan’s dilemma.

Promising the Unachieveable?

But to return to the Krugman story, after many years of deflation people simply hang on to cash instead of spending it in the expectation of price rises in the future, even if the demand shortage itself is being caused by a lack of investment which results from a shifting population structure.

“If this is the problem, there is in principle a simple, if unsettling, solution: What Japan needs to do is promise borrowers that there will be inflation in the future! If it can do that, then the effective “real” interest rate on borrowing will be negative: Borrowers will expect to repay less in real terms than the amount they borrow. As a result they will be willing to spend more, which is what Japan needs. In short, this explanation suggests that inflation–or more precisely the promise of future inflation–is the medicine that will cure Japan’s ills”.

So the idea is this. According to standard macro theory in order to get an economy stuck in a never ending recession being fueled by the expectation of future price falls back onto a dynamic growth path you need to generate negative real interest rates to push people into saving less and borrowing and spending more – basically you need to make it more expensive for people to hold on to money.

Now given the zero limit associated with the conventional application of interest rates it isn’t easy to generate negative interest in the here and now, so one proposal is to go for second best and give the impression they will exist in the future and thus change behavioral patterns by changing expectations. This you try to do by generating the expectation of significant inflation in the future.

This expectation is hard to achieve due to the credibility attached to the inflation fighting credentials that developed world central bankers have built up in recent decades. Despite the fears being raised by some monetary hawks that all and every kind of central bank balance sheet expansion will lead to out-of-control inflation, the general opinion is that central bankers are responsible people who will be effectively able to pull the plug on any excessive liquidity easing (or “exit”) just as soon as the inflation they are trying to provoke starts to raise its ugly (or should that be beautiful) head. In the liquidity trap situation the result is that you are not able to generate sufficient inflation expectations to be able to achieve even low single digit inflation.

So what you get is a kind of chicken and rooster game between central bankers and the citizen in the street, where the central bankers have to credibly convince the world they have “lost their heads” and become sufficiently frustrated and irresponsible as to be willing to go beyond earlier constraints and really put the pedal once-and-for-all hard down on the metal. Maybe if, instead of limiting themselves exclusively to the verbal registers of communication they broadened out the channels used they would have more success. Instead of wearing suits and ties to their monthly meetings, maybe if they wore swimming costumes or t-shirts and colorfully framed sunglasses that would work.

Now you could say, where’s the problem with generating 2% inflation? It doesn’t sound that reckless since most central banks in the developed world have inflation targets at or around that level. But simply declaring a 2% inflation target in Japan is not sufficient, partly because people are doubtful after so much time that the bank is capable of doing it, and partly because even if that hurdle could be overcome, the expectation of 2% would not be enough to change behavior sufficiently to unleash the required consumption. So in the Japan case what the Bank of Japan is being asked to do is ramp up the policy approach to such an extent they seem to be flirting with the possibility that they may not be able to stop what they start, and that inflation could easily significantly overshoot the 2% mark. If they can’t raise this doubt, so the argument runs, consumers will factor-in the effectiveness of the exit strategy, lower their expectations and adopt behavioral strategies that mean the economy doesn’t achieve the required escape velocity to break out of inflation.

All of this naturally assumes that what actually ails Japan is a run of the mill liquidity trap. Now I don’t doubt the capacity of the Bank of Japan and the Japanese government, in the last resort, to generate enough concerns about whether or not they know what they are doing to lead people to start to anticipate an “out of control” situation (see more below), but what I do doubt is that even assuming this feeling of things being out of control feeds through to a 2% inflation level (and not say a sudden and dramatic run on the yen) that this inflation will be sustainable. More probable, I think, if the economy is in a demographically driven deflation trap is the economy, following a short-sharp-burst of inflation slumps back yet one more time into long run deflation. The reason I think this is that if the deflation is the result of a savings/investment mismatch brought about by long term demographic changes – rather than by say “garden variety” deleveraging (or a “balance sheet recession”) – then I don’t see why the supposed “trap” wouldn’t come into existence again once the bank started to roll back its balance sheet.

To some extent Krugman himself admits the difficulty:

“This theory is offensive to many people. Deep economic problems are supposed to be a punishment for deep economic sins, not an accidental byproduct of swings in the birth rate. Inflation is supposed to be a deadly poison, not a useful medicine. Above all, it seems implausible that the proposed solution to such severe difficulties could involve so little pain. And while I think logic and evidence are on my side–that demography, not crony capitalism, is the villain, and inflation is the answer–it is certainly possible that I am wrong”.

In another article from the same period – “Further Notes On Japan’s Liquidity Trap” – Krugman offers us the following curious, but clarificatory, argument:

Japan – like any liquidity trap economy – in effect needs inflation, because it needs a negative real interest rate. The slightly paradoxical conclusion which I believe to be true is that the deflation we actually see is the economy trying to achieve inflation, by reducing the current price level compared with the future. ……….

So, he says, Japan’s economy is trying unsuccessfully to achieve the inflation it needs. Leaving aside the implicit animism of the argument, I would counter by saying “No! Japan’s economy is in fact desperately trying to deflate, and is only frustrated in doing so by the massive liquidity easing from the central bank and the ongoing fiscal injections it receives”. The difference between this deflation and all previous variants known to economists is that this deflationary process is not a simple deleveraging one, but something without end, a way of life, since the economy is seeking an equilibrium point which no longer exists. That is what the deflation is about, the economy is striving to find an equilibrium without being able to locate one.

The “Further Notes” article (again, see the Japan section on this site) also makes one other fundamental point – that his inflation conclusion is not something born “like Athena from the head of Krugman” but is rather the logical outcome of applying universally accepted models based on standard neoclassical assumptions.

“I think I should make it clear that I did not start with this conclusion, then make up a model to justify it. What I did instead was start with a very orthodox model – the same sort of model that is favored by people who are vociferously anti-Keynesian and pro-price stability – and ask under what conditions it could generate the apparent ineffectuality of monetary policy we see in Japan. And the need for inflation pops out – to my own surprise, by the way. If you refuse to accept this conclusion, either you must offer some alternative model, or you are saying that your opposition to inflation comes not from analysis but from gut feelings”.

He is right. If Japan’s economy is just another planet that has temporarily slipped off its orbit then inflation is what it needs. If something more fundamental is happening then the policy remedy is, to say the least, questionable. Japan’s economy may or may not be striving to achieve inflation, but I would no go so far, as Krugman does with those he disagrees with, as to suggest he has some hidden desire to get things wrong. I simply think he is not following his own argument through to its own logical conclusion, he is hovering half way across the rope bridge without finally and decisively striding forward to the other side. He has seen the problem has been produced by a violent fall in the birth rate, but can’t really get to grips with whether or not monetary policy can handle this problem.

I can understand his caution, since he is also right that what is needed now is an alternative model to the standard neoclassical growth one, and possibly a whole new way of thinking about macroeconomics, even if – collectively speaking – we don’t have either the former or the latter right now. What we do have is an accumulating body of evidence to suggest that Japan, despite all its specificities is not unique, that developed world outcomes are increasingly not in concordance with what conventional theory would lead you to expect, and (at least in my own personal case) a gut feeling that the policy remedy being applied in Japan is a rather dangerous one.

The Black Swan Question

“Since everyone eventually gets through the deleveraging process, the only question is how much pain they endure in the process. Because there have been many deleveragings throughout history to learn from, and because the economic machine is a relatively simple thing, a lot of pain can be avoided if they understand how this process works and how it has played out in past times.” Ray Dalio, An In-depth Look At Deleveragings

Those who do not think about what is happening in Japan in demographic terms (a list which would not include Paul Krugman) normally rely on a theory based on the idea of “balance sheet recessions“. At the heart of this theory (which is often associated with the name of Nomura economist Richard Koo) is the idea that economies like the Japanese one are essentially deleveraging following a bubble related unsustainable expansion of credit and debt. The demand side deficit can thus be thought of as being produced by this deleveraging process on the part of households and corporates. Most financial market participants assume that some such deleveraging process is what ails the economies of the developed world as a community. I think the kinds of demographically related arguments we have gone over above suggested that use of the deleveraging idea may be a significant over simplification of what is happening.

Japanese households are not borrowing more on aggregate due to the fact that they are still deleveraging from earlier excesses, and corporates are not neglecting to invest more in domestic Japanese activities for similar reasons. Rather, consumers are now borrowing less and less as the age profile and size of the entire consuming community steadily shifts while corporates are hoarding cash as investing in capacity without the necessary expansion in demand makes no economic sense. The structural deficiency in demand which produces the inflation is not an “accidental by-product” of “swings in the birth rate” but an absolutely comprehensible and systematic outcome of fertility dropping well beyond replacement levels and staying there over several decades.

This is not the conclusion drawn by legendary Hedge Fund manager Ray Dalio, who concluded after studying a large number of deleveraging processes that “everyone eventually gets through the deleveraging process” the only real difference being in how much pain is inflicted on participants in executing the operation. Which brings us to “rara avis in terris nigroque simillima cygno”, or the phrase from the Latin poet Juvenal recently brought near the headlines by financial affairs writer Nassim Nicholas Taleb which roughly traslated means means “a rare bird in the lands, very much like a black swan”. Such a bird was long thought not to exist, since all known swans were white.

In fact, the issue of black swans is not exclusively associated with the issues made famous in Taleb’s book on the subject (the question of random tail events), but has its origins in a basic flaw in inductive reasoning, long ago highlighted by the philosopher of science Karl Poppper: you simply can’t assume something doesn’t exist because you have never seen one. Ray Dalio falls into this trap in the exert which opens this section when he asserts that everyone eventually gets through the deleveraging process. It would be more correct to say that everyone had gotten through the process, and then Japan came along. Two decades after the bubble burst, according to the balance sheet recession people, the country has still not gotten through the process, and if the arguments I am presenting here are valid it is highly unlikely it ever will do. In which case the existence of a black swan in the first (simply epistemological) sense of the term may serve to bring one into existence in the second sense in the shape of a very nasty unexpected tail event as expectations are forced to verge violently from one direction to another.

The problem is that almost all investors at this point are assuming that the country will eventually overcome its deflation problem, and indeed markets are positioning as if it were inevitable that it would (producing large and systematic price distortions) even if this inevitability is accompanied by the idea that if at first they don’t succeed, then they will try try and try again till they do. Or put another way, that the Bank of Japan will simply keep ramping up its money printing activity until the country obtains escape velocity. In fact Ray Dalio uses his logical fallacy in his inductive argument about deleveragings to justify a change of pricing in European periphery risk assets, as I explain in this post here.

But another possibility exists, one which has already been highlighted by another legendary investor, George Soros. The Japanese currency may be precipitated towards an out of control collapse.

To understand how and why this might happen we need to think about how it could be possible for the Bank of Japan to produce inflation. Since the country’s economy has a known structural weakness on the demand side, demand pull inflation is unlikely to occur however much money printing goes on. So it would have to come from the other, or supply, side in the form of cost push inflation. This is not so difficult to generate, since you only need to introduce the expectation that the central bank will use monetary techniques and the currency will, as we have been seeing, fall. The only question here is how far it has to fall to produce a given level of inflation. As of March 2013 the currency had fallen approximately 30% against the euro in 9 months while deflation still remained at a 0.5% annual price decrease rate on the Bank of Japan’s targetted measure.

So more will need to be done. But just how much more. But let’s imagine for a minute that the yen is devalued such as to produce, say, 1% inflation due to rising import costs. What happens next? Well, as we saw earlier, a lot depends on expectations. If import prices remain unchanged during the following year since the value of the yen remains stable, then the induced inflation simply drops out of the system, as it did in Japan in 2009 following the short price burst produced by the 2008 inflation, or as it does in countries that apply a one off consumer tax hike (Japan itself in 1997, just before deflation really took a tight grip, or many countries on the EU periphery at the present time).

So the issue is, will people anticipate further downward movement in the yen to induce even more inflation? Will the central bank be “responsibly irresponsible” and feed not only those expectations but expectations that the devaluation will continue every year while the 2% target exists? And how will “mum’n pop” Japanese savers react, by spending more, or by moving their money out of the domestic currency to avoid some of the value loss? Soros thinks there is a very real chance that the latter will happen, and I agree with him. What’s more, I think it is much more likely that ordinary Japanese savers reach the expectation that the currency value will fall than they do reach the conclusion that ongoing inflation will be induced.

My conclusion then is that there is little evidence or possibility that this policy will work as advertised, largely because it is based on a misunderstanding. It might work if Japan was in a simple liquidity trap as described by Keynes, or a balance sheet recession deleveraging process of the kind Richard Koo talks about. But once you introduce demography into the picture, as Krugman does, the game gets changed and the water incredibly muddied.

Japan is stuck in a shrinking population trap, and neither monetary nor fiscal policy will adequately solve the problem. Continuing to run fiscal deficits in a deflationary environment will only means that government debt is pushed onward and upwards leading to a variety of possible scenarios as to what the end game will finally be. Reining in the deficit, by raising consumption tax, for example, will probably only make deflation worse with a one year time lag, as happened in 1997, and will almost certainly force the economy into more economic shrinkage which in any event makes the debt issue worse.

On the other hand the current BoJ policy while effectively driving down the yen is producing very little in the way of visible inflation. What it is doing is systematically misallocating financial resources across the planet, as those who are convinced that Ray Dalio is right put their money behind their intuition. Italian ten year government bond yields for example hit 3.94% last week, their lowest level since November 2010 based on the idea that at the end of the day, even if the country’s debt (currently at 127% of GDP) does continue to rise Japan style, it doesn’t matter that much since the ECB will surely one day “go Japanese”. Italy is in fact the EU country most similar to Japan in terms of growth and demographic issues.

But if Japan itself cannot go Japanese in the sense of generating the anticipated inflation then the implication will be that neither can anyone else who gets stuck in a similar quandry. Black swans may indeed be very rare birds, but that doesn’t mean you may not be able to sight one flying past the bottom of your garden at some point in the not too distant future.

Comments are closed.