Chart of the day: what is the high yield bond spread telling us?

Bond markets are often seen as more prescient in anticipating economic slowdowns than stock markets. Yield curve inversion has predicted every recession in the US since 1970, for example. Inverted yield curves are a leading indicator of recession because they are signs of expectations that the economy will be so negatively impacted that it will force the central bank to ease rates in the future.

During the last recession, economists like Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke speculated that signs of yield curve flattening and inversion were not prescient because of an alleged "global saving glut".

I would not interpret the currently very flat yield curve as indicating a significant economic slowdown to come…

An alternative perspective holds that the recent behavior of interest rates does not presage an economic slowdown but suggests instead that the level of real interest rates consistent with full employment in the long run–the natural interest rate, if you will–has declined.

Given the global nature of the decline in yields, an explanation less centered on the United States might be required. About a year ago, I offered the thesis that a "global saving glut"–an excess, at historically normal real interest rates, of desired global saving over desired global investment–was contributing to the decline in interest rates.

–Ben Bernanke: Reflections on the Yield Curve and Monetary Policy (Before the Economic Club of New York, New York, New York, March 20, 2006)

This perspective proved false when recession did come late in 2007.

Bloomberg is running a story that indicates this same inverted curve harbinger may be at play again:

The so-called Treasury yield curve, adjusted for distortions caused by the Federal Reserve’s record low zero to 0.25 percent target interest rate for overnight loans between banks, shows that two-year notes yield 20 basis points, or 0.20 percentage point, less than five-year notes, according to Bank of America Corp. research. The unadjusted gap of 79 basis points at the end of last week indicates the chance of recession at about 15 percent.

I am a bit sceptical of this ‘adjusted’ curve talk. Nevertheless, the data have been weakening.

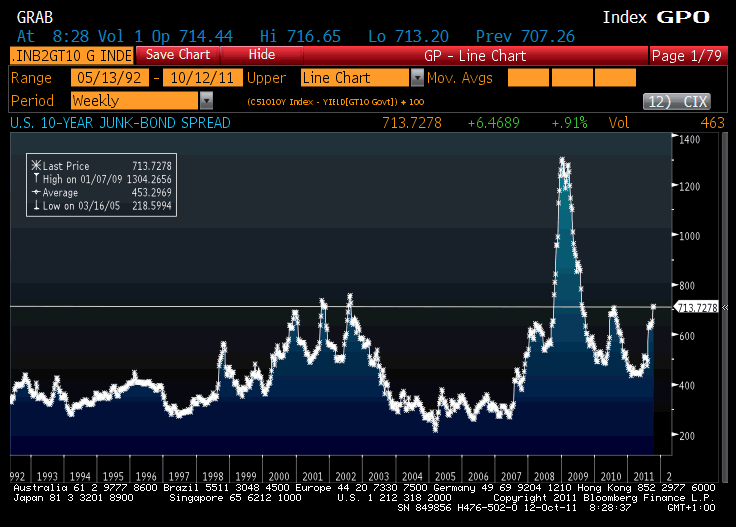

What about high yield. An increased spread between high yield and government bonds is often seen as a harbinger of economic downturn as well. As the economy rolls over, more marginal debtors feel stress first and this gets reflected in bond yields. Bond funds reduce risk and the spread between safer bonds and high yield bonds increases.

The extra yield investors demand to own bonds from investment-grade companies worldwide reached 277 basis points, or 2.77 percentage points, on Oct. 5, the widest since July 2009, before declining to 275 yesterday, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch index data. Spreads on high-yield, high- risk debt globally in the U.S. reached 932 basis points on Oct. 4, the highest since September 2009, before narrowing to 897.

Here’s the chart courtesy of Andy Lees.

What do you see? Not everyone thinks this is telling us things will get worse. Some see value. Bloomberg again:

“We are beginning to look at high yield again,” Andrew Sutherland, head of credit at Standard Life, said in an interview at the company’s office in the Scottish capital. “If markets turn around, that sector could snap in very quickly. We wouldn’t want to miss it, but are pacing ourselves very gradually. High yield still looks attractive.”

I see this as a macro call. High yield is attractive if you think that the economy will rebound. if not, the extremely low high yield default rate will rise considerably, as will yields.

Ed – I think BB was right on his specific comment but missed the bigger implication of what he was saying. I think we did have a global savings glut that was pressing interest rates down (and still do) – however the reason for the glut is concentration of wealth and income. Wealthy people have a high marginal propensity to save whereas poor/middle class people have a high marginal propensity to consume. When all the gains from productivity are going to the top 1%, the demand for investment opportunities grows significantly, however there is very little demand growth, thus few good places to invest. This drives risk-free rates down (and also incidentally causes bubbles and ponzis as people chase yield). BB failed to recognize that the global savings glut was the flip side of the coin to an incrasing shortfall in demand. This had been papered over by increasing leverage, but that game was on its very last legs in 2007.

I think you can chart high yield right alongside the other “risk on” investments and it would correlate quite nicely. So yes I agree with your last paragraph Edward, and would expand it further to say that almost everything in the investing world is currently a macro call and can be generally lumped into “risk on” versus “risk off” groups that roughly move in tandem.

Given the ECRI’s and Dr. Hussman’s recession calls and slowing economic data across the board, with several countries vowing further austerity, I’m inclined to be in the “risk off” side of the bet right now.

To me the interesting story that will unfold a few quarters from now is how will northern European countries feel about bailouts when their own country goes into recession?

I too have been thinking macro because it dominates the landscape now. If the economy turns down, it’s risk off. If it stays adloat it’s risk on. That’s been the dynamic since mid-2010. But I thought Niels Jensen’s piece was interesting in this respect because he was saying that most of the news has been priced into ‘value’ stocks, meaning he thinks that stocks are so beaten up, especially in Europe, that he wants to start accumulating them. What I read him saying is that there are enough companies with good prospects in any environment that, given how low their price is, they are worth buying. In that sense he was making an anti-macro call.

The interesting bit is stocks have really rallied since he wrote that piece about the point of maximum pessimism. Yes, stocks were oversold and government bonds were overbought but still I think this view is something to consider too.

Excellent point about Jensen’s piece, which I caught earlier this month as well and which gave me pause in my equity bearishness. I think he said that Germany and France’s CAPE were currently around 10, which is historically quite low.

Unfortunately on the other hand, the S&P 500’s CAPE (20.7) makes that market roughly twice as expensive as northern Europe’s–which is hard to believe amidst the constant cacophony of “U.S. stocks are cheap” from the Wall Street peanut gallery. The fact is both the CAPE and the Q-Ratio for the U.S. markets are about 25-40% over their historic averages. So unless “this time is different” and CAPEs are now permanently elevated versus their pre-1995 norms, then I expect to see the U.S. markets decline from here in the near- and medium-term.

But back to Germany and France, those valuations are indeed compelling, although Jensen urged cautious consideration of EUR currency risk as well. If the EUR drops as much as the German/French equity markets gain, then it was all for naught for a foreign investor. EUR hedging seems prudent in that bet.

Seems like we would have to take into account that is was private debt in trouble in the past and sov debt in trouble (and being manipulated) now