Is There A Eurozone Credit Cycle?

By Edward Hugh

America, we know, has a currency union that works, and we know why it works: because it coincides with a nation — a nation with a big central government, a common language and a shared culture. Europe has none of these things, which from the beginning made the prospects of a single currency dubious.

Paul Krugman – Can Europe Be Saved?

All theory depends on assumptions which are not quite true. That is what makes it theory. The art of successful theorizing is to make the inevitable simplifying assumptions in such a way that the final results are not very sensitive.’ A “crucial” assumption is one on which the conclusions do depend sensitively, and it is important that crucial assumptions be reasonably realistic. When the results of a theory seem to flow specifically from a special crucial assumption, then if the assumption is dubious, the results are suspect.

Robert Solow, A Contribution To the Theory of Economic Growth, 1956

One of the key premises underpinning the establishment of the Euro as a common currency to be shared by a number of individual national states rather than one single nation was the central idea that the several economies of the participating countries would eventually converge to one common typology. That is to say, even if the individual nations would not be dissolved into one single superstate, then the idea was that the difficulty this could obviously create would be overcome by the generation of a number of different, but to all-important-economic-effects identical economies, each one a replica (in miniature or “a lo grande”) of the other. Absent this, it is hard to see how people could have convinced themselves that having a single currency and a single monetary policy could possibly work in the longer term.

Convergence Towards a Common “Steady State”?

This critical idea of convergence was based on a simple (and possibly rather simplistic) application of the kind of neo-classical economics widely taught in the modern university. Every economy, it is postulated, is capable of generating some sort of relatively constant “steady state” growth rate , and given the application of sound common monetary policy and an appropriate mix of relevant structural reforms these relatively constant growth rates should not diverge too much one from the other, since if they did, and continued to do so on a sustained basis, then a fiscal mechanism would need to be created to serve as a stabiliser able to redress the consequences of such steadily diverging rates of growth with the associated large differences in living standards. Political consensus could never realistically be maintained behind a process which was manifestly generating inequality between participating countries.

Naturally, if there was no eventual convergence then any fiscal mechanism which was created would need to be something more than an ad hoc fund for handling the impact of a one-off asymmetric shock (like the bursting of a property bubble), since it would need to be permanent and systematic and operate in a way which is broadly similar to the internal redistribution mechanisms which operate between north and south in countries like Spain and Italy, or between rich and poor states in the USA. Naturally, in the course of the current crisis, no one with any degree of institutional authority even in the most desperate of moments has been prepared to publicly contemplate the possibility that the creation of such a territorial equalisation mechanism might eventually be need, even though, as will be argued here, successfully saving the Eurozone will almost inevitably mean putting just such a fiscal compensator in place. Just think about it: the Greeks never had a fiscal deficit problem at all, since what was lacking was adequate compensation for their growth imbalances! You can just see the anxious (or enraged) look on all those German faces. Yet just this is the conclusion that I think can be drawn about the creation of a common currency area among a group of countries where convergence is not operative, since the consequence of not doing so, as is now becoming clear enough, is that the countries with lower underlying growth profiles become steadily weighed down by the burden of their indebtedness to the higher growth economies – that is to say debt obligations are created where fiscal transfers are lacking.

Now, as we all have come to know only too well, this kind of fiscal mechanism was neither contemplated by the founding fathers of the Euro, nor has anything even remotely resembling it been envisioned as part of the collective response to the present crisis. Indeed the need for its creation remains one of the most highly controversial topics in the current debate (rivalling in the emotional charge it engenders only the suggestion that some sort of internal devaluation might be needed for the zone’s struggling peripheral economies). Advocacy of this move has been restricted to commentators outside the mainstream, most notably among them Wolfgang Munchau (see here, and here), and for his pains he has acquired the honorary title of “Enemy of Spain” from the Spanish newspaper El Mundo, who presumably found his suggestion that Spain might need to be a beneficiary of such a mechanism an insult to their national honour.

Diverging Not Converging Economies?

Meanwhile back in the world of the real economy, nothing could be more evident from all the signs we are seeing during the present recovery than that the Euro Area economies are not converging – indeed they are visibly diverging in all manner of different ways. Some economies are now called “peripheral”, and others are called “core”. Yet neither the core, nor the peripheral economies resemble the other members of their sets in a way which standard theory might lead you to expect that they should.

France is a domestic consumption driven economy, running a goods trade deficit, where manufacturing industry seems to be losing competitiveness, while Germany has weak domestic consumption, is completely export driven, runs a large external surplus, and German manufacturing industry seems to get more (rather than less) competitive by the day.

Among the peripheral economies Greece would seem to distinguish itself for its extreme fiscal profligacy, while Italy and Portugal have just passed through a decade of slow growth, which contrasts with the case of Spain and Ireland where fiscal deficits and government debt were not a large issue during the first decade of the Euro’s existence, but where a growing mountain of private sector debt (fuelled by negative interest rates and a growing housing bubble evidently was) evidently was.

The consequences of needing to accommodate policy to this diversity of economic “types” have, however, still to be recognised, yet the lessons of why convergence hasn’t occurred do need to be assimilated, otherwise effectively staying in denial will only raise the chances of an eventual disorderly disintegration of the zone itself. Interestingly, Poul Thomsen, IMF Mission Chief for Portugal recently emphasised in the context of the bailout there that as far as the IMF is concerned, “Every country is different and there is no one-size-fits-all for the programs we support”. How long will it be before this message reaches Frankfurt?

As an anecdotal aside, I cannot help having the feeling that the practitioners of academic neo-classical economics spend far too much of their time building models based on premises which remain far from self-evident in order to tell the world how it ought to be, leaving the pathways through which empirical facts-on-the-ground could work their way back to influence or modify the initial assumptions rather obscure, to say the least.

To give one example, on a recent visit to the monetary policy department of one of Europe’s smaller central banks I found myself engaged in a rather frustrating debate about the relative merits of competitive devaluation and structural reform as ways of getting heavily-indebted export-dependent economies back to economic growth and job-creation in sufficient volume to be able to start paying down the debt. Unfortunately the discussion became a rather unrewarding “dialogue of the deaf” of the kind to which I have by now become so accustomed. In fact the whole think so evidently became so tiresome that one of the ever courteous central bank participants took me aside on my way out to reassure me that “there was of course nothing personal in our exchange”. Well, of course not! But that being said, the debate did seem to me to be rather asymmetric and one-sided, because while I am absolutely convinced you need structural reform alongside any (hypothetical) competitive devaluation (otherwise all the old ills simply return), the other side of the argument obviously does not accept the need for competitive devaluations to accompany structural reform. Au contraire, the one is seen as the complete and much more desirable alternative to the other.

During our discussions, in my frustration at the fact we were obviously getting absolutely nowhere, I asked the central bank representatives what it would take to convince them they were wrong. Surely, I asked, if the economies in question did not return to a reasonable and sustainable growth rate within the next 3 to 5 years, then they would need to ask themselves whether or not they had been doing something wrong. I for my part clearly recognise that if those economies I consider to be in need of competitive devaluations to underpin structural reforms do achieve significant and sustainable economic growth over the next five years without them then I have been missing something, somewhere (in fact I consider such recognitions of reality to be in my own best interest, to be taken on board on a “sooner the better” basis). Yet,“no”, came the answer, loud and clear, “that would simply mean that the structural reforms had not been deep enough or sufficiently energetically implemented”.

I am now put in mind of a recent (and rather infamous) press conference given by the Real Madrid football club coach José Mourinho. When asked by one of the journalists what responsibility he felt his players and he had in the recent series of defeats by their rival Barcelona FC, “zero” was the answer he gave to the astonished journalist. Well, there you go, learning by doing in action!

Am I the only one to find something strange (and even frustrating) about this kind of answer? What is the connection between the fundamental assumptions of the kind of economics that is being applied in this crisis on Europe’s periphery (which in many ways means prioritizing micro and ignoring the core theorems of applied macro) and reality? And how do we test these assumptions? Surely anyone with any kind of scientific frame of mind should look for facts that can confirm (or better, following in the footsteps of Sir Karl Popper refute) the hypotheses they advance. Which brings us back to the lack of symmetry in the argument we are having at the moment. I personally do consider the lessons learnt from our attempts to handle the crisis to form a vital part of the knowledge acquisition process. As I say, I for my part am clear that if these economies do return to reasonable and sustainable growth within a 3 to 5 year time horizon, then there will be something wrong with the way I have been going about things. On the other hand, since several hundred million Europeans are currently being subjected to a massive social and economic experiment, it would be a pity if economic theory were to prove itself unable to learn anything substantial from the eventual outcomes.

In the meantime I find myself gasping for air, trying to pin down threads in the argument that can be examined and tested, which is why I think the convergence issue is important, since either convergence is taking place or it isn’t. Put another way, is convergence taking place across a meaningful, in the here and now, time horizon, or is it simply one of those things which is only destined to happen in the longest of long runs by which time, as Keynes so tactfully put it, we will all be well and truly dead? Evidently the future of the Euro depends on the kind of answer you give to this question, and the conclusions you draw from that answer.

Business Cycles and “Business Cycles”

Now one of the areas in which mainstream economic theory surfaces in search of some real world air is in the context of what many analysts call the “credit cycle”. This concept is interesting, since it allows for the introduction of some data, and enables us to take a look and see if the real world is as theory (and all those models they work with) imagines it should be.

In fact, the idea of a credit cycle is a natural offshoot of the idea of a business cycle, insofar as central banks pass though an interest rate cycle which maps to some extent movements in the business cycle (that is to say as the economy slows rates come down, and as it accelerates they go up), while demand for credit in the private sector of the economy tracks movements in both of the aforementioned cycles. That is to say, private demand for credit declines during recessions (despite the fact that interest rates fall, and public sector demand for credit rises to offset this drop and cushion real economy impacts), while the subsequent recovery in the demand for private sector credit can be seen as one of the key indicators influencing central bank decision taking when it comes to interest rate policy, since an over-rapid expansion in credit can produce excess demand which can lead to inflation, and in a “normal” world central banks tend to want to fend off any unwarranted surge in inflation or in inflation expectations.

The problem with all this is that business cycles are not such straightforward beasts as they are often assumed to be, nor is it really clear how useful conventional business cycle theory really is during a structural (as opposed to cyclical) crisis like the one we are presently living through. Evidently in every economic expansion (or contraction) there is a structural and a cyclical component, and normally the former is less important than the latter in explaining short term movements in output, but during the present crisis this situation has been reversed in both the developed and the developing economies. Take the following charts illustrating recent growth patterns in the Spanish and Chinese economies, can anyone really spot the cyclical components, since I sure as hell can’t.

Spain didn’t have a single quarter of contraction following the ending of the 1992/93 contraction until the great global economic crisis broke out, and China hasn’t had one during this century at least. Obviously in each case there are reasons for these phenomena (catch up growth, inappropriate expansionary monetary policy lifting you through the roof), but the only point I want to make is that they are clear examples of where structural elements far outweighed cyclical ones, and I would argue that this situation is much more common than is often admitted.

So, we need to be very careful, and in the context of the current global recovery we need to be be at great pains in trying to distinguish between cyclical and structural components in growth, whether this is in the context of growth in GDP or in private sector credit.

A Eurozone Credit Cycle?

Now one of the points of core dogma which is institutionally enshrined at the heart of the ECB is that aggregate Eurozone data has some sort of useful, or valid, or interesting interpretation. So strongly is this belief held that the central bank representatives seldom examine interpretations of the data that drill down and try to identify what is happening (and more importantly why it is happening) at the individual country level. This is hardly surprising since as suggested above, the very existence and survival of the Euro is seen as hanging on the idea that (given the appropriate country level structural reforms) all the individual economies will converge, and any recognition that tailor-made monetary policies are needed for individual countries would be tantamount to accepting that the founding assumptions of the monetary union had sprung a leak.

However, as we will see, credit conditions do in fact vary widely across member countries, and this uneven availability-of and demand-for credit across the Eurozone has become just one more headache to add to the far from small number policy-makers at the ECB currently have, since the growing economic recovery in some countries is being facilitated by the relatively easy availability of credit, while in others problems resulting from a debt overhang and a lack of competitiveness are only reinforced by the difficulties their banking systems face when trying to provide new credit to viable enterprises and solvent households.

In any event, starting with the aggregate data released by the ECB such as it is, we find that Eurozone-wide bank lending – which has (truth be told) remained far from strong since the official ending of the recession – lost some of its limited momentum in March, suggesting any real recovery in aggregate Eurozone domestic demand is still a long way off. Private-sector lending increased during the month by 2.5% over March 2010, after rising by 2.6% year on year in February. In fact, the recovery from the economic and financial crisis has been characterised across the Eurozone by weak bank lending, particularly to businesses, and although the annual growth rate of loans to non-financial corporations rose in March, it continued to expand at the relatively modest rate of 0.8% following a 0.6% rise in February. Loans to households have been doing slightly better, and grew at a 3.4% rate compared with the 3.0% registered during the previous month. The annual growth rate of lending for house purchases grew to 4.4% in March from 3.8% in February.

(The legend and titles in the above chart are in Catalan, since they have been taken from a report by Catalunya Caixa, but if you bear in mind that “Societats No Financeres” are private sector corporates, “Llars: Consum” is household consumption and “Llars: Habitatge” is home mortgages then you shouldn’t have too much difficulty, especially if you remember that the economic net worth of this data asymptotically approaches zero, in the sense that the more time you put into trying to understand it the less you will really learn about how the Eurozone actually works).

At the same time broad money, or M3, rose by an annual 2.3% (M3 comprises currency in circulation, overnight, short-term deposits and debt securities of up to two years, repurchase agreements, and money market fund shares), and the three-month moving average of the annual rate of change of M3 was +2.0%. Thus monetary growth still remains well below the ECB’s reference value of +4.5% for the three-month average, a monetary growth rate it considers to be broadly in line with an inflation rate of just under 2% over the medium term, implying there is little risk that broad money growth will push up inflation in the eurozone, although it is unlikely that this particular detail will cut much ice with policymakers at the ECB in relation to their interest rate decisions, since it is not monetary fuelled demand-side pull that worries them, but rather commodity induced supply-side push, and in particular the impact this could have on inflation expectations.

Credit Tightening Or Credit Loosening? Spain & Germany Compared

The latest ECB quarterly bank lending survey suggested only a moderate tightening of credit standards for both enterprises and households in the current quarter. But as I am saying, this appreciation of the aggregate situation conceals significant differences at the individual country level. In Italy, France, Finland and Germany (for example) credit seems to be widely available, while in Spain, Portugal and Greece credit conditions remain very tight. The Bundesbank noted only last week that in Germany there had been a “marked easing of credit standards in lending to both enterprises and households” in the first quarter of this year and that surveyed banks expect little change in credit standards in the current quarter. This view was reinforced by the Ifo Institute who reported that the percentage of German firms which have difficulty accessing credit fell by 1.1 percentage points in April to a record low of 22.6%.

Meanwhile in Spain, the central bank state in their latest quarterly report on the economy that notwithstanding the reduced tension in capital market attitudes towards the country, “accessibility by the resident private sector to funding became somewhat tighter”.

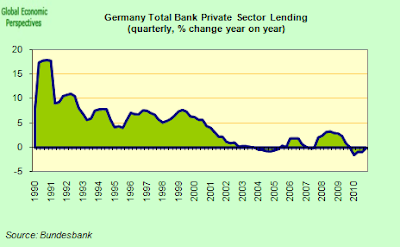

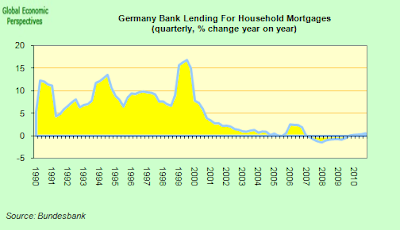

The peculiar thing here though, is that if you look at the comparative inter-annual rates of change the two countries don’t seem to be that different.

What is apparent is that in each case (Germany or Spain) and regardless of whether or not we are talking about total private sector lending, corporate lending or mortgage lending, the rate of increase in borrowing is extremely low, with the only significant difference between the two countries being that in the German case such extremely low rates of credit growth date back to the turn of the century, while in the Spanish case they area recent phenomenon following the bursting of the housing bubble. (I have dealt with this comparison between Spain and German at greater length in this post here).

The big difference between these two countries is, of course, the level of international competitiveness of their economies, since Germany is well able to live with such low levels of domestic credit growth due to its strong export capacity, which enables the country to generate significant GDP growth (currently over 3% annually). Spain’s economy, on the other hand, has been unable to expand export capacity fast enough to compensate for the sharp loss in domestic consumption, and hence what little growth there is has been supported by a substantial government fiscal deficit and even this has still left the economy continually flirting with recession.

Further, in the German case credit conditions are comparatively loose even though there is no great demand for additional credit, while in the Spanish one credit conditions are tight (for a variety of reasons) so potential home-buyers and companies have difficulty getting as much credit as they would like to have, and this despite the fact that prevalent interest rates in both countries are broadly similar, and result from one common monetary policy.

And Then There Is Portugal & Greece

In fact Spain is not unique in this sense, even if the country does offer a somewhat dramatic example of a larger problem. Credit conditions in Portugal are also now tightening, and demand for loans is falling.

And we find a similar picture in Greece.

What is most remarkable about these charts for Spain, Portugal and Greece is how they so resemble each other in the sharp decline in credit to the private sector. Nor should any up-tick be expected since all these countries are already heavily in debt, and the only serious way for them to attain sustainable growth is to de-leverage via export-induced saving. That being said, this transition is likely to prove, as we all know, pretty painful. Even during the German transition from 1999 to 2005 things weren’t entirely easy, yet these three countries now face a far more difficult and far more demanding challenge, given the scale of their external debt and the current market conditions.

Who Needs More QE And Doesn’t?

To help them move through that challenging process what they arguably need, in the same way as the UK and the US do, is some form of quantitative easing. Unfortunately excessive reliance on aggregate data leads ECB policy-makers to miss this relatively self-evident fact. So these countries are being asked to make a structural transition of almost monumental proportions without carrying out a competitive devaluation, with accompanying monetary and fiscal tightening. It is hard to see a successful outcome, and indeed I imagine we won’t see one.

But the monetary union’s problems don’t end here, since there are another group of countries where monetary easing from the ECB does appear to have been having an impact, and where credit growth has, to some extent taken off. The first of these would be Italy.

Now there is little to alarm us here, since Italy’s private sector is not especially indebted, but it is interesting to see how the pattern varies, and how credit conditions in Italy are very different from those elsewhere in Southern Europe. On the other hand, if we move across the continent to Finland, once more we find little sign of difficult credit conditions:

Indeed, the low interest rate policy of the ECB during the crisis really does seem to have worked in the Finnish case, in that housing demand and private consumption never really collapsed (see this earlier post on the property boom in Finland). Finally, in this brief survey, there is France, where even though corporate borrowing remains restrained, demand for consumer and housing credit seems to be really kicking back to life.

Evidently France is becoming a very special case, since France’s private sector is not heavily indebted, although looking at its comparatively young population profile it could easily become so. If there is one country where a property bubble could be produced, that country is France – for both demographic and low-indebtedness reasons (just look at the line of take-off for household mortgages in the above chart). So evidently, at least in the French case ECB tightening makes perfect sense, as it does when we look at the inflation expectations chart.

So Just How Many Sizes Do We Need To Fit All?

The purpose of this brief survey of credit conditions in a number of individual Eurozone countries has been to draw attention to one rather neglected area of policy difficulty. It is common knowledge that having a “one size fits all monetary policy” can prove problematic, in that the application of negative interest rates to an economy that is essentially booming can lead to significant structural distortions, and even produce asset bubbles of one class or another.

But the issue of credit conditions and credit availability is normally given far less attention, even though it is an equally important one. It is clear that it is hard to identify one common “credit cycle” among the zone’s diverse economies, and indeed the need for credit is always going to be very different in an economy which runs a large and continuing external surplus when compared with an economy (like France’s) where domestic consumption remains strong and the country continues to run an external deficit.

It is clear that some of the difficulties which were likely to be faced by countries attempting to handle the rigidities associated with participating in a common currency were well anticipated in advance, even if few of those involved in setting it up were able to listen at the time of its creation. Other problems which were not so clearly foreseen have emerged with time. The difficulty presented by surrendering powers from your own central bank with respect to monetising government debt is only now becoming clear, as is the problem created by acquiescence in the kinds of structural distortions which permit the accumulation of high levels of external debt, debt which fickle markets may suddenly decide they are no longer willing to support. The fact that cheaper interest rates might lead to larger fiscal deficits and growing government debt was foreseen, but the danger presented by ever larger private indebtedness funded by external borrowing surely was not.

However, the problems entailed by the absence of any meaningful common credit pattern and the consequent difficulty of maintaining the core idea of ongoing convergence raises perhaps one of the most serious obstacles to Euro credibility and continuity, since, as I try to argue at the start of this study, even the issuing of Eurobonds and the creation of a common fiscal treasury can only represent a stopgap measure in such a situation given that what this then produces is a constant and ongoing transfer of resources from one set of countries to another. This outcome is neither sustainable nor is it desirable, since voters in the funding countries will eventually grow tired of it (even under the rather dubious hypothesis that they were willing to entertain it in the first place) while those who are funded would find themselves in the unpleasant situation of having their long term dependency institutionally re-enforced, even as they find themselves watching a steady trickle of their educated youth moving towards the funding countries in search of better remunerated work.

Basically it is not clear at this point whether this growing mountain of associated system-management problems really is capable of being digested and resolved, but one thing is surely very evident, and that is that not talking about them won’t make them go away. It really is high time the ECB stopped boxing itself into a corner by examining monetary policy impacts only at the aggregated data level, and started to analyse and identify policy implementation impacts at the individual country level. Simply throwing the issue back to the various national governments by saying “this is your problem, what you need are more structural reforms” is no response at all. This will be especially true if the proposed structural reforms prove not be sufficient to handle the scale of the problem, since this will only produce an even greater loss of confidence in the Euro than that which has been sustained to date, precisely the outcome that ECB governing council members must be anxious to avoid. Or will we be told that the structural reforms implemented simply were not deep enough. What has been argued here is that the idea of a common Eurozone-wide credit cycle associated with ongoing convergence between member state economies could be regarded as a “crucial simplifying assumption” in the sense used by Robert Solow in the quote at the start of this study, an assumption which underpins the whole theoretical apparatus on which the common currency is based. The question is, after ten years of operation, does this assumption still remain plausible and reasonably realistic?

Such a scenaris is unworkable. The US has had different cycles within the country for different regions for decades, and yet is still not harmonised. Only extreme events impact all the country simultaneously, like the credit crunch. So why should a eurozone any different. In fact with the different psychology of each state there will be attitudes to debt and leverage. The UK and Ireland borrowed heavily yet France and Germany were much more cautious. To harmonise credit cycles there will need to be a harmonisation of attitudes and with completely different personalities and languages that is unlikely.

Such a scenaris is unworkable. The US has had different cycles within the country for different regions for decades, and yet is still not harmonised. Only extreme events impact all the country simultaneously, like the credit crunch. So why should a eurozone any different. In fact with the different psychology of each state there will be attitudes to debt and leverage. The UK and Ireland borrowed heavily yet France and Germany were much more cautious. To harmonise credit cycles there will need to be a harmonisation of attitudes and with completely different personalities and languages that is unlikely.