When I was thinking about writing this post earlier in the weekend I was only going to stress the GDPNow number. And the point was to reiterate how well the US economy was doing pre-coronavirus. And then I was going to make the abrupt transition to the oil market, since I have telling you this is where the rubber hits the road for a liquidity crisis, defaults, and bankruptcy.

But events in the oil market have overtaken that plan and I’ve decided to give the freefall in oil equal billing. In fact, just as I was starting this post, an alert popped up on my iPad from Bloomberg News, saying “Oil markets fell the most since the U.S. war in Iraq in 1991, hammered by the coronavirus and a price war involving Saudi Arabia and Russia”.

So, how should I lead? Should I start with the good news or the bad news?

Let’s start with the good news, if you don’t mind

The pre-coronavirus economy

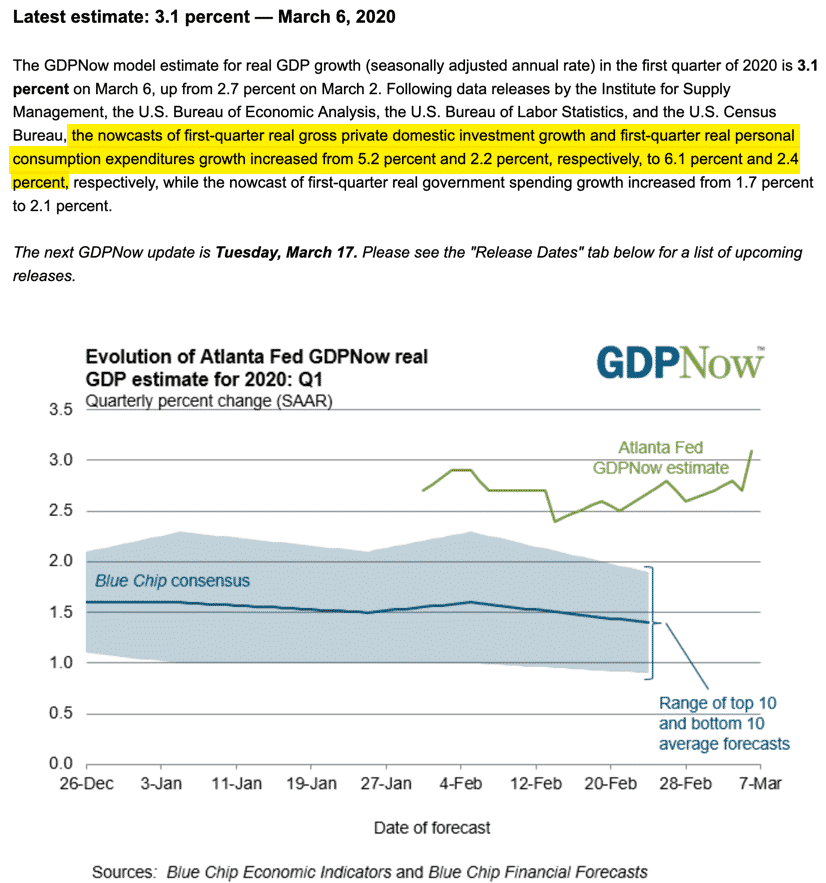

So, I saw this GDPNow print after I posted on Friday and I thought it dovetailed really nicely with what I was saying about there being a massive break between data before mid- to late-February and data afterward. The GDPNow number, even though it’s a nowcast, it really only incorporates backward looking data. And so it gives you a perfect look at the immediate past.

Look at these numbers.

The 3.1% number isn’t the thing to focus on, even though that’s pretty good. It’s the investment figure at 6.1% and the increase in consumption growth. What those two numbers are telling you is that the capex recession of 2019 was over as 2020 began. Firms were ready to ramp up on capital expenditures in 2020. Moreover, the numbers were increasing – both for investment and consumption. So, that tells you the momentum was to the upside. Add that in to the jobless claims and jobs numbers we saw at the tail end of last week and you had the makings of a nice Q1.

That’s good news

The bad news

Unfortunately, we are in a different world now. I think that if the NBER dates a recession in 2020, it will be from right about now, because that’s when the numbers will start to decline precipitously. The question is how far they fall – and then over what time frame.

The NBER does not define a recession in terms of two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP. Rather, a recession is a significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy, lasting more than a few months, normally visible in real GDP, real income, employment, industrial production, and wholesale-retail sales.

That’s how the NBER puts it. And they are only going to make that determination in retrospect, not as the data come in, which is what you probably would want. And remember, we will have to see it in income, employment and sales figures for several months, not just in production for a couple of months to call it a recession.

But, let’s be clear: the data thus far in 2020 are pointing to an accelerating economy, not recession. The bad news is that this is coming to a screeching halt right now.

To give you a sense of how far things have to fall though, think about Q1 2020. If the Atlanta Fed’s numbers are right, even if we see no growth in March, Q1 still comes in at 2%. If the economy contracted 3% in March, we’d still get 1% growth. So things have to fall pretty aggressively for Q1 to be a bad number. I don’t think that’s going to happen.

What could happen is that the numbers for industrial production and sales fall due to lost consumption and supply chain bottlenecks. That precipitates inventory builds and eventually layoffs, hitting both consumption and employment. When that happens and it lasts through, say at least the most of the summer, you might have a recession.

This is the scenario we are looking to avoid. And the telltale signs it’s happening are probably going to be most immediately reflective in initial jobless claims since those come every week. That’s a data series I will be watching.

Russia’s gambit

A lot of this is going to be exacerbated by what’s happening in the energy sector. Let me explain how I am thinking about it.

First, there’s OPEC+, which is essentially OPEC plus Russia. On Friday, they met. And Vladimir Putin had a plan. Russia’s energy minister Alexander Novak told his Saudi counterpart Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman that Russia was not going to cut production. Doing so as the coronavirus raged would just give the US shale industry a lifeline. And US frackers have basically become the swing producers globally by adding millions of barrels of daily production to the market, while OPEC+ restricted output.

Russia now believes this is an opportune time to squeeze the US producers. Why? For one, Russia is sick of Trump using energy as an economic and political weapon. US sanctions to prevent the Nord Stream 2 pipeline from Siberian natural gas fields to Germany is one thorn in Putin’s side. But the Venezuelan production of Rosneft, a Russian state-owned producer is another big problem.

Another big reason is the Russian economy. They have gone through five years of austerity and structuring business to mitigate the impact of US sanctions. That makes it easier for Russia to withstand lower oil prices. Moreover, Putin also plans to turn on the fiscal taps this year. And finally, a weaker ruble helps Russian exporters, which sell their wares mostly in US dollars.

For months now, the Russians have been telling the Saudis they were not willing to cut production anymore. And so, they have decided now is the time to stop.

The Saudis pile on

Now, remember, the Saudis tried this gambit five years ago. And they failed. I was just looking at a post I wrote in December 2014 called “Saudi Arabia’s price war and the oil and Russian ruble crisis” to refresh my memory on what was happening. This paragraph from then sounds exactly like what the Russians are doing:

What I see the Saudis saying here is that they see too much supply on the market. In the old policy regime, they would have tried to get OPEC together to restrict output and maintain prices. Trying to cure this excess supply by restricting output would, they believe, continue to erode their market share, which would work against them over the long-term. Therefore, they will let the market work its magic at present output levels, allowing the highest cost oil to leave the market and letting the market settle at whatever price it settles in at. The Saudis want to become price makers instead of price takers. And this constitutes a major change in policy regime for OPEC and Saudi Arabia.

The difference this time is that we have a one-two punch because the Saudis have now joined the Russians in deciding to flood the market with product. Here’s Bloomberg News:

Saudi Arabia plans to boost oil output next month to well above 10 million barrels a day, as the kingdom responds aggressively to the collapse of its OPEC+ alliance with Russia.

The world’s largest oil exporter engaged in an all-out price war on Saturday by slashing pricing for its crude by the most in more than 30 years. State energy giant Saudi Aramco is offering unprecedented discounts in Asia, Europe and the U.S. to entice refiners to use Saudi crude.

At the same time, Saudi Arabia has privately told some market participants it could raise production much higher if needed, even going to a record 12 million barrels a day, according to people familiar with the conversations, who asked not to be named to protect commercial relations. With demand ravaged by the coronavirus outbreak, opening the taps would throw the oil market into chaos.

Oil Price Collapse

This is trouble.

Just before I started this, futures markets opened for oil and that’s where the Bloomberg News headline I spoke of at the outset came from. We’re seeing a 30% decline in prices practically overnight. And that’s on top of the near double-digit percentage decline we saw on Friday.

So, forget this being a ‘bear market’. It’s an out and out crisis for the energy sector. We’re talking about a major liquidity crisis as weak credits in the US shale space are shunned. Defaults and bankruptcies are inevitable. The question is how widespread this becomes. Goldman is talking about $20 oil now. That would have the hallmarks of a bust as great if not greater than the 2015 shale oil bust.

And remember, this comes in addition to the real economy effects of the coronavirus.

The liquidity crisis

What we need to be looking out for are signs that this metastasizes in some way. Credit markets had their worst day in a decade on Friday.

The credit-market meltdown was the culmination of a week in which investors withdrew the most cash in at least 10 years from U.S. funds that buy corporate bonds and loans.

“This is what the start of a recession after a long bull market feels like,” said John McClain, a portfolio manager at Diamond Hill Capital Management. “This is the first day of seeing some panic in the market.”

While stocks have sold off over the past two weeks in dramatic fashion, the drop in credit had largely been orderly until now, market participants say. They’re bidding securities even lower to get trades done, making transaction costs that much higher. For some, it’s the first time they’ve experienced such volatility in their careers.

Let’s see what happens when markets open on Monday. If we see the type of panic we saw on Friday, I would suggest three things.

- First, it is a sign that the liquidity event is not just limited to the oil patch but is a wholesale move out of risk assets including bonds. With the majority of investment grade bonds now rated BBB, this means investors looking to re-position into safe assets must pile into the Treasury market.

- Second, if we see continued panic in credit markets writ-large then the energy space is toast because it is generally of much lower quality and the dynamics of a plummeting oil price will bring those issues to the fore.

- The Fed is going to have to cut. I think we hit zero on the Fed Funds this year if this credit event extends for any length of time. Financial conditions are now tightening pretty quickly. Despite what people like St. Louis Fed President Jim Bullard have been saying, if this remains in place by the FOMC meeting, we will get another cut then too, maybe 50 basis points. And then the Fed will quickly move to zero

The Fed’s rate actions won’t be enough to stop a credit crunch from having real economy effects though. So, we’ll just have to see what other measures they will take if it gets to this.

My View

Almost none of what I wrote today is specifically coronavirus-related. And so, that tells you that we have serious problems ahead of us. Financial fragility is acute. And so, this coronavirus pandemic is going to test not just our health crisis systems and our economic resiliency, it is going to test our financial system and liquidity crisis management as well.

It’s hard to talk about upside scenarios in this environment. A lot of downside risks are proliferating right now. Let’s see how markets react when they open on Monday. I’m expecting a lot of volatility. And if we do get a liquidity crisis and credit crunch, recession scenarios like PIMCO’s have to become the base case.

Comments are closed.