Mortgage REITs’ leverage poses significant risks to the overall mortgage market

By Sober Look

With the GSEs (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) forced to shrink their balance sheets (see discussion), the private sector will need to step in. As demand for mortgages increases with the growth of the US population (see discussion), the federal government will simply lack the political will to allow the GSEs to accommodate this new demand – particularly after the spectacular taxpayer bailout of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in 2008 and numerous capital injections by the US Treasury since then.

But the private sector mortgage providers will not always be banks. With capital requirements increasing under Basel-III and other regulatory pressures, the banking sector growth may also be limited.

Bloomberg: – More than half of the top 25 U.S. banks aren’t earning enough to cover their cost of capital, leading to stock prices that are “significantly lagging previous global recoveries,” according to the note. “The vast majority of the reduction relative to pre-crisis levels is attributable to structural issues like deleveraging and regulatory reform.”

One development in this space that some say may be poised to meet the rising mortgage demand has been the explosion (52% increase between 2010 and 2011) of Mortgage REITs (mREITs). They are publicly listed trusts that operate similarly to their cousins in commercial real estate but focus on residential mortgage securities or sometimes pools of mortgages. These include companies such as American Capital Agency (AGNC), Hatteras Financial (HTS), and Annaly Capital (NLY).

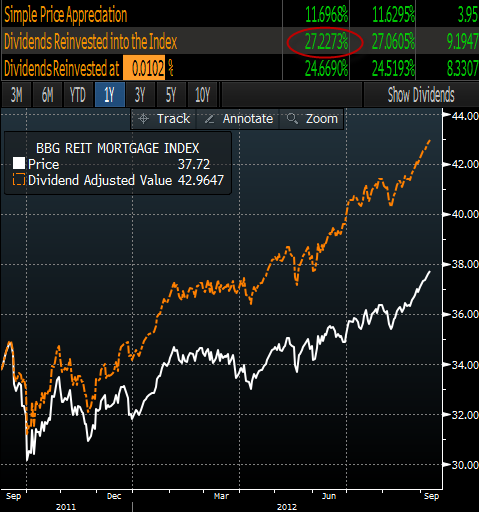

Anyone looking at these firms will notice that they have outperformed most asset classes over the past year. And a large portion of that outperofrmance has been from high dividends. The Bloomberg mREIT index shows 27% total return from a year ago, with less than half of that coming from price appreciation.

|

| Bloomberg mREIT index |

mREITs have been rapidly coming to market with IPOs and secondary offerings this year. A number of these, such as Putnam Mortgage Opportunities, American Capital Mortgage Investments, Pimco REIT, Apollo Residential Mortgage, etc., have been sponsored by some of the largest US asset managers.

In a trend that is quite similar to other fixed income asset classes (see this discussion), a great deal of the new capital for these products is coming from ETFs. With the popularity of mREITs, REIT ETFs growth has also exploded. Take for example Market Vectors Mortgage REIT Income ETF (MORT). The chart below shows MORT’s shares outstanding growth since the ETF’s launch.

|

| MORT shares outstanding (Bloomberg) |

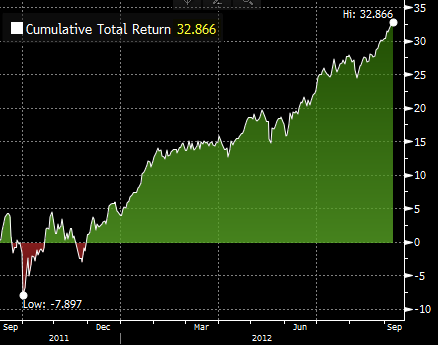

The performance of this ETF has been tremendous, explaining some of the demand growth.

|

| MORT total return, incl dividends (Bloomberg) |

So how is it that a mortgage product can generate some 30% return in a year when the universe of mortgages securities generated roughly 3.4% over the same period? The answer as always is leverage. Mortgage REITs are able to pay high dividends because of the tremendous leverage they maintain. What’s more, they tend to finance long-term mortgage securities with short-term repo. Typically they borrow from banks for 60-90 days and just roll their loans. Banks don’t have to use much capital for securitized short-term loans, so they generally extend credit lines to REITs with no trouble. The repo lines to mortgage REITs have grown as quickly as the assets. The financial crisis of 2008 had little impact on the growth, which has been close to exponential.

| Source: JPMorgan |

The asset-liability mismatch has been the most troubling aspect of this business. Both Bear Stearns and Lehman were brought down due to their inability to roll short-term repo in a similar setup (not due to derivatives as is commonly believed). The advantage that mREITs have is that they tend obtain term repo lines rather than the overnight financing that investment banks ran prior to the crisis. That means if their lines are pulled, REITs have 2-3 months to sell their securities. And the average term of financing has actually increased recently – which should help with stability.

| Source: JPMorgan |

The danger of course is that the Fed maintaining extraordinarily low rates for a long time will generate tremendous demand growth for such leveraged product, as assets continue to increase exponentially. Everyone will get comfortable with mREITS “always” making money. Then interest rates will begin to rise and the 30% returns will quickly turn into -30% (or worse) as leverage works both ways. At the same time banks will get concerned about their massive exposure to REITS via repo lines and will inevitably require more collateral for the same amount of repo loans or shrink/pull the credit lines altogether. This deleveraging could result in a disastrous scenario of forced selling and rising mortgage rates – and as in 2008 falling mortgage securities prices will precipitate more forced selling.

It is great to see the private sector step in for the GSEs to meet some of the excess mortgage demand. But unlike banks who are limited in their ability to grow leverage (although it is quite high) and have access to deposits and the Fed for funding, the deleveraging of these “shadow banking” entities could pose a significant risk to the US mortgage markets (and potentially the economy as a whole) should interest rates begin to rise.

they in vest in nearly exclusively agency MBS … at the worst of the 08 crisis, fnm 2007 mbs never traded below 95

@ beej – good point.

The other item that this post conveniently overlooks is this nice little data-free unsupported contention:

“Then interest rates will begin to rise and the 30% returns will quickly turn into -30% (or worse) as leverage works both ways.”

The author just conveniently leaves off explaining how or why interest rates will rise. It’s like saying that if a gigantic meteor were to strike the earth, we would all die. While, yes, that would be the result, you don’t just operate under the (unsupported) assumption that it’s going to happen. Without a coherent and realistic thesis as to how any appreciable rise in interest rates is going to occur any time soon (say, 5 yrs), the thrust of the entire post loses most of its credibility.

There can be a rapid rise in interest rates on the interbank market, which would be outside Fed control. While the Fed would inevitably flood the market with liquidity to bail out the banks the problem is that confidence would be shot. Even now banks prefer to deposit excess reserves with central banks rather than each other years after the crisis. Leverage needs to come down and not transferred from on sector to another. Overall private sector leverage is excessive and holds the rest of the nation to ransom.

@ Lazarus –

While LIBOR rates can temporarily deviate from the Fed Funds rate, these two generally track EXTREMELY closely. See graph here: https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=aA4

The rest of your argument, i.e. ‘leverage needs to come down’, I agree completely. And all of this points to very low interest rates for the foreseeable future.

Yes I know that LIBOR and Fed Funds Rates track very closely, though my comments were more about an extreme panic. That could still happen.

Longer term though the problem is low interest rates. They are toxic to everyone. They discourage savings and encourage asset bubbles. They slow the formation of families and new businesses. A new start up needs asset prices to be low as these add significantly to the fixed costs of any new business. If this is not addressed then all the pain of readjustment is done through wages and that makes for a very weak economy going forward. Look at Greece, wages are falling yet the economy has nowhere to go but down for now.

+30 becomes -30 when rates “begin” to rise? Sounds pretty “Armageddon” to me. If a black swan — say, war with Iran or the collapse of Europe — causes a sudden rate spike, then sure, you will probably get some carnage. But if current trends continue, the scenario will be gradual and not for some time, which AGNC, et al. provide for with hedging. As for banks suddenly calling in their repos, that scenario assumes a bubble, and renewed investor interest in mortgage securities coming off a depression like this is not what most “sober” analysts would call a bubble.