Staring Into The Ukrainian Economic And Political Abyss

By Edward Hugh

It’s been a long time now since Paul Krugman spoke of the Ukraine economy epitomising the arrival of what he then termed the “second great depression“, and its been an even longer long time since we lay awake at night dreaming about the coming conquests of the Orange Revolution. It’s also been a good time since I looked at and wrote about the country, so now may be as good moment as any to do so.

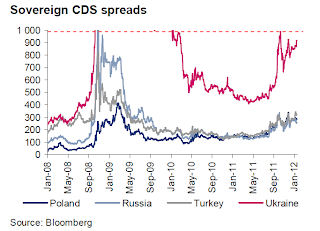

“Ukraine’s efforts to seek cheaper natural gas from Russia rather than comply with the terms of a bailout have alarmed investors, propelling the former Soviet republic’s credit risk above Argentina’s for the first time in two years. The government is shunning the International Monetary Fund as it struggles to agree on discounted fuel imports from Russia, with whom clashes halted European gas transit twice since 2006. That’s fanned concern over its ability to meet $11.9 billion in debt costs this year, with default risk rising more than any country Bloomberg tracks except Greece in the last six months.”

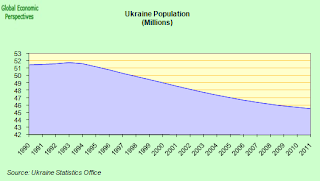

Ukraine is once more getting into a mess. Part of the problem is political, part of it is economic, and part is a combination of the two. On top of which Ukraine has one of the most severe demographic problems in the CEE, which is itself a region of severe demographic problems. So what we have are a cluster of problems just waiting for the perfect storm to gather.

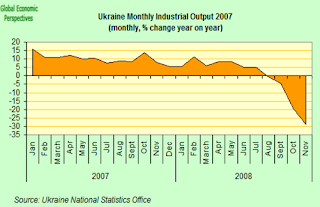

As is well known, Ukraine was one of the worst affected countries following the onset of the global financial crisis. Industrial output slid – great depression style – by more than 30% in a matter of months (the chart Krugman used was of course mine), largely due to a massive overdependence on steel, the price of and demand for which had fallen off a cliff.

The onset of the crisis also brought to light the way the country had been living on an unsustainable credit boom fueled by short term forex borrowing in the years prior to its arrival, and as the fund flows which had been financing this rapidly reversed Ukraine was sent running into the arms of the IMF, and rapidly accepted a $16.5 billion standby loan in November 2008.

As the IMF put it in their programme documentation:

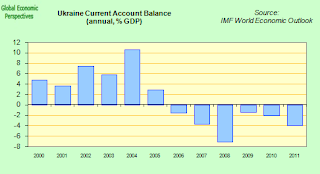

Ukraine’s current account and growth performance relied strongly on favorable terms of trade. From 2003 to mid-2008, the price for steel, which accounted for 40 percent of Ukraine’s export and 15 percent of GDP at the time of the crisis, had increased fourfold and prices for gas imports were still far below world market prices, providing little incentive to improve Ukraine’s dismal inefficiency in energy use. Nevertheless, by 2007 the current account had already deteriorated strongly as imports had surged on the back of a credit and real estate boom and an overheating economy. Private sector balance sheet imbalances widened sharply with foreign currency loans accounting for nearly 60 percent of total loans, often extended to borrowers without foreign exchange income, and bank funding increasingly relying on short-term borrowing from abroad.

A Love Hate Relationship With The IMF?

Well, for those familiar with the region there is nothing particularly strange about the imbalances and the credit bust. But as the Fund itself makes clear in its ex-post evaluation of the first crisis programme, relations between the multilateral institution and the Ukraine administration have been far from easy over the years:

Ukraine has had long but complicated program relations with the Fund. From 1994 to 2005, the Fund supported Ukraine through six arrangements. Completion of reviews tended to be difficult, as only 13 of the envisaged 24 reviews were completed, of which 10 with delay or involving waivers. The Ex Post Assessment of Longer-Term Program Engagement in 2005 (IMF Country Report No. 05/415) found that “Fund-supported programs had a mixed record in achieving their objectives. While the programs were quite effective in supporting macroeconomic stability, they did not succeed in accelerating the build-up of more market-friendly institutions.”

Unfortunately things did not go that much better this time, and the initial programme was terminated after the second review and a disbursement of $10.4 billion:

“Program implementation was difficult against the backdrop of sharp political divisions. Only two of the envisaged eight reviews were completed, with the first review already delayed by three months due to failure to reach understanding on fiscal and banking related policies in the midst of political wrangling between the president and the prime minister…..After the second review was completed on time in June 2009—reflecting some progress with the bank resolution strategy, announcement of future plans to increase gas prices, the adoption of a restructuring strategy for Naftogaz, and a slowdown in foreign exchange interventions—the Fund remained closely engaged with the authorities. But the program went off track as ownership vanished and fiscal policy diverged further from the program”.

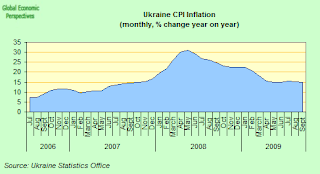

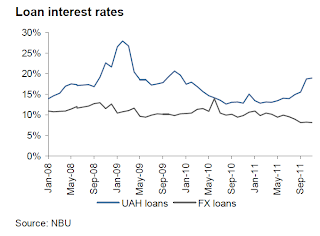

In fact here we see three of the key Ukraine issues all lined up together – energy prices and the fiscal deficit, problems in the banking system and constant foreign exchange interventions to maintain a currency peg with the US dollar, a peg which encourages unnecessary forex borrowing while fueling inflation at continually high levels.

Running such consistently high inflation simply leads to rigid monetary policy, high interest rates, and inadvertently enhances the attractiveness of foreign exchange borrowing (which is the ultimate undoing of these pegged economies) since interest rates are much lower elsewhere, the currency is fixed (so where’s the risk) and wages keep going up and up along with the inflation. You seem to be getting better off than your peers in the country you peg to, but in fact you are simply sliding steadily towards the precipice. In many ways things on the Euro Areas Southern fringe are only different in terms of degree. I can still remember Spain’s now ex-Prime Minister José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero telling his compatriots that they were steadily moving towards the top of the EU per capita wealth league, overtaking Italy, and then France, just before the bubble burst, and the house valuations which lay behind those impressive appearances started tumbling.

Frustrated and fed-up, the IMF cannot simply ignore the country. Ukraine is simply too large and too strategically situated to be allowed to go AWOL. So when the new Ukraine government requested a further standby arrangement in the early summer of 2010 there was little alternative but to agree (shades of Greece and the EU) and make an additional $15.1 available to the country, bringing the outstanding borrowing to $25.5 billion. And here comes the rub: according to the IMF, Ukraine is due to repay $2.4 billion this year; $3.5 billion in 2013 and $1.3 billion in 2014. This is quite an onerous schedule for a country which is now struggling to finance itself in the financial markets. Many of the current IMF programmes in Europe have the look of success, until the time comes to pay back.

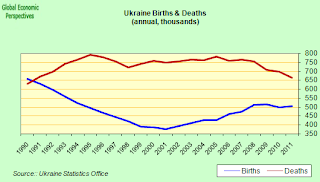

Predictably the second programme didn’t proceed any more smoothly than the first one, and the first review was only approved after a lengthy tussle about pensions, with the Ukrainian government eventually ceding to pressure and in July 2011 passing a pension reform whereby the female retirement age was raised from 55 to 60, and the duration of pension contributions needed for entitlement increased by 10 years.We will return briefly to this topic, but it is instructive to note that while most economic analyses of the current crisis (everywhere, not just Ukraine) fail to mention the underlying demographic issues, the problem of how to pay for pensions keeps cropping up time and time again. The need for the reform was obvious, with a rapidly ageing population the country, despite being poor, had one of the most generous systems on the planet. In 2010, the last year before the reform, Ukraine spent 18% of its GDP on pensions and had a pension fund deficit of UAH 34.4 billion or 3.2% of GDP.

Despite this relations between the fund and the Ukraine administration failed to improve substantially (they have now been bitten too often) and at the end of August 201 an IMF staff team was sent to Kiev to carry out the second review of the new programme. The review was never formally completed, and the IMF announced on November 4 that negotiations had been broken off.

It’s All About Gas

Gas prices are an issue everywhere, and especially in election years, but in Ukraine, due to the geopolitical situation, they take on a special significance. Negotiations between Ukraine and Russia over the supply and payment of gas and terms of transit for Russian gas to Europe have been a recurrent theme since the end of the Soviet Union. During 2011, as gas prices rose by an annual 60%, Ukraine repeatedly sought to renegotiate the 10-year contract signed in January 2009. The Ukraine administration considers the gas price formula unfair and the gas price – currently US$416/mcm in 1Q12 – too high. The two sides have now been working for some months in an attempt to reach an agreement, but it is still not clear one will be reached.

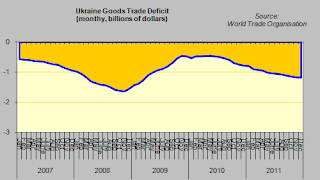

Gas is a core issue for both the Ukraine and the IMF due to its impact on both the current account deficit and on the level of domestic consumption. It is evident that Ukraine growth is now slowing and coming under threat from rising energy prices. Morgan Stanley estimate that the country had a non-energy current account surplus of 8.2% of GDP in 2011, but since it ran an energy deficit of 14.1% of GDP, the outcome was a current account deficit of 5.5% of GDP.

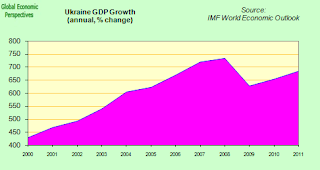

To slow the rate at which this current account deficit is eroding reserves and undermining the stability of the currency, the Ukraine central bank has tightened monetary policy sharply, which in turn has contributed to the rapid deceleration in growth, which consensus forecasts put at around 3.0% in 2012, but which may eventually turn out to be significantly lower. To put this slowdown in perspective, despite the fact that Ukraine’s economy has been growing steadily since the 2009 annus horribilis, output levels are still below the pre crisis peak. As Capital Economics’ Neil Shearing puts it:

“Ukraine grew by 5.2% last year, which, on the face of it at least, seems a decent outturn. But context is crucial. In 2009, output contracted by a whopping 15% – a recession from which the economy is still recovering. What’s more, the pace of recovery has actually been somewhat disappointing. Output is still well below its pre-crisis peak [see my chart below – EH] yet growth already appears to be slowing. In Q4 GDP expanded by 4.6% y/y, down from 6.6% y/y in Q3. At current rates of growth, it will take another two years for output to return to pre-crisis levels. But even this could be a tall order given how vulnerable the economy is to a fresh escalation in Europe’s debt crisis”.

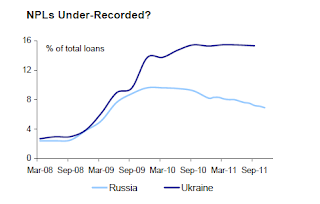

In addition to the energy price constraint domestic consumption in Ukraine is still weighted down by the indebtedness problems created by the earlier boom. Non-performing loans are still running at a very high level, although no one really seems to know quite how high, since there are major question marks hovering over the official figures. The IMF’s permanent representative in Ukraine Max Alier estimated in the spring of 2011 the figure might be as high as 30% of total loans. And with every 1% drop in the value of the hryvnia the proportion rises, due to the extent of forex borrowing.

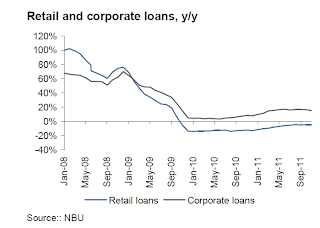

In addition, with many Ukraine banks being owned by parents in other EU countries, the credit crunch in the west is rapidly transmitted to the east. Corporate lending growth is slow, and the steady contraction of household borrowing is following a path which looks very similar to that seen in Southern Europe, or the Baltics.

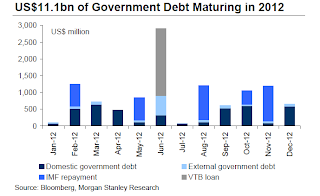

Ukraine – like Hungary – badly needs an agreement with the IMF to facilitate the financing of debt which needs to be rolled-over this year. These rollovers will put significant strain on the system, Neil Shearing estimates something of the order of 34% of GDP.

“Meanwhile, Ukraine faces external debt servicing costs of $52.5bn (around 30% of GDP) this year. A large chunk of this debt is in the banking system, but roughly $5.4bn is owed by the government ($3.5bn of which is due to the IMF). Put together, we estimate that Ukraine’s external financing needs are close to $58bn this year – equivalent to 34% of GDP.”

Obviously, with so much debt needing to be rolled over, the country is very exposed to any sudden reversal in risk sentiment, just as it was in 2008. It needs to be under the sheltering wing of the IMF, but this time round the dynamics are rather different. In particular, countries which once got a large net benefit from IMF lending are now facing the moment of truth – when they need to start paying back. Unfortunately, and for whatever reason, the programmes sponsored by the IMF – in Ukraine, in Latvia, in Hungary, in Romania, in Greece, in Ireland, in Portugal – are not yielding the benefits which were initially claimed for them by the advocates of the “structural reform path”, in particular in the growth area.

In addition, years of fiscal austerity are now starting to take their toll on the populations concerned. Expectations are not being fulfilled, and a backlash is underway. Regular readers will be aware that my baseline case in Europe is that these misguided/insufficient programmes will steadily destabilise the political systems on Europe’s periphery, leading to unstable and unpredictable outcomes. Not the kind of stuff would-be investors like.

Evidently it would be unfair to blame the Fund itself for the kind of problem which exists in Ukraine. Clearly it is a very complex and difficult-to-handle situation. But if you haven’t gotten hold of the full extent of the problem in the first place, then it is hard to offer recipes which open a sustainable path forward. Read as much as I can, I still fail to be able to find any single mention of the issue Ukraine’s dire demographics presents for future growth prospects in the IMF literature.

The country’s population is falling steadily, due to a long run excess of deaths over births and a steady outflow of working age population, leaving to seek a better life elsewhere. This is not only causing the population to shrink, it is also leading to a dramatic change in the age composition of the population, increasing the average age of the workforce, and lowering the number of those employed per person retired. This is the strategic importance of health and pension system reforms in a country like Ukraine.

Naturally structural reforms are important, but they need to be part of a mix of policies, and among these doing something to address the country’s demographic death-spiral should be given a great deal more importance than it is presently – where in fact the issue is almost absent from economic debate.

At this point it is hard to say how the present stand off between the IMF and the administration will work out, but as in the Hungarian case I have the feeling that most mainstream bank analysts are underestimating the capacity of the political system to produce “bad outcomes”.

The macabre ”culebron” associated with the apparent medical condition of the country’s former Prime Minister – in prison for having signed the last gas deal – only adds to the sense of surreal drama associated with the country’s potential default.

Ukraine’s ex-premier Yulia Tymoshenko is ill and in constant pain, Canadian doctors who examined her in prison said, adding that authorities denied her key blood and toxicology tests. A team of Western doctors went last week to the prison where Ms Tymoshenko is held to examine the opposition leader amid complaints about her treatment and health.The three Canadian and two German medics included a cardiologist and a nervous system expert, the former Soviet republic’s penitentiary system said in a statement.“

After meeting and examining Ms Tymoshenko, it was the Canadian opinion that she required confidential blood and toxicology testing,” doctor Peter Kujtan said in a letter to Ukraine’s ambassador in Ottawa, Troy Lulashnyk.The medical team had been invited by Ukraine to carry out the examination and even brought along diagnostic equipment which could produce on-the-spot test results, Dr Kujtan said.“But Ukrainian authorities refused to allow its use, stating that we would be breaking several laws of the land and could face prosecution,” he said.

Now here’s the “official version” via interfax:

Ukraine’s jailed former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko needs no surgery, the State Penitentiary Service cited a seven-member medical panel as saying on Friday after Tymoshenko had extra checkups on Thursday.The findings of an X-ray test confirmed the previous diagnosis and meant there was no need to revise “the recommendations for her preliminary treatment, while changes that have been detected do not warrant surgical treatment,” a statement from the Penitentiary Service cited the seven doctors as saying in their assessment. Tymoshenko, who had herself requested the additional checkups, was examined at a clinic in Kharkiv, the city where her prison is situated. She had an X-ray test, a computed tomography scan and a magnetic resonance imaging scan. However, she again refused to have a blood test, the Penitentiary Service said, adding that foreign doctors would need the results of a blood test for the final diagnosis and treatment recommendations.

Naturally this sort of thing is not new in the country, and anyone with an interest in reading about a similarly surreal situation some years ago might like to read my “Will The Real Ukraine Central Bank Please Stand Up! ” post.

And if you have the kind of sense of humour I have about technical issues, you might appreciate this short list of concerns about the way the bank problem resolution issue was handled by the central bank, as voiced by the IMF in their ex-post first standby agreement review:

a) Liquidity provided to insolvent banks: As it was difficult to distinguish between solvent and nonviable banks, liquidity support was likely extended to the latter. Moreover, the maturities of NBU loans, which originally ranged from 14 to 365 days, were later converted up to seven years providing de facto solvency support.

b) Relaxation of collateral requirements: Banks’ own shares were accepted as eligible collateral despite the significant risk for the NBU.

c) Mandatory purchases of bank recapitalization bonds: The NBU was required to purchase at face value recapitalization bonds issued by the government, a practice that the Fund staff advised against.

The first point is an important one in any traditional approach to bank resolution, distinguishing between the rescuable and the un-rescuable, but, of course, none other institution than the ECB itself has now crossed the line, and with the 3 year LTROs (which will, naturally, be extended) the central bank is offering, as the IMF suggest in the Ukraine case, solvency support to a number of otherwise insolvent banks. On the collateral side, the ECB isn’t accepting bank shares as collateral, yet, although it is accepting nearly everything else, and this idea of the central bank buying recapitalization bonds, wasn’t it first tried and tested in Ireland, and hasn’t it be applied to some extent in Greece? Nuff said, I think.

What Can’t Go On Forever Will Only Go On As Long As It Can

So where do we go from here? The IMF have dug their heels in about gas, but this is only a symptom of a much deeper sense of frustration. The fund has been financing the Ukraine deficit and cheap gas, but will the money disbursed ever get returned, or will the can be continually kicked down the road. It is worth remembering that the initial financing of 11 billion SDRs was equivalent to 802% of the country’s quota, a very large quantity in terms of the standards of 2008. As the fund puts it in the review:

“No major shift in policy making occurred and political economy considerations continue to drive policy making in Ukraine. Efforts to tackle the underlying structural and institutional weaknesses stalled. Bank resolution remained incomplete, the exchange rate regime returned to pre-crisis practices, the energy sector remained largely unreformed with quasi-fiscal deficits widening, and legal and governance reform fell short of objectives”.

Put crudely, the fund was being used to finance cheap energy to win votes for populist governments. The frustration to be seen in the above summary suggests to me at least that coming to a new agreement won’t be as easy as many think. Especially with a number of other countries looking on. It all used to be called moral hazard I think.

Only industrial users in Ukraine currently pay the full cost of gas. Residential users pay something like 30% of the cost of the gas they consume. This subsidy is a key cause of the loss suffered by the state-owned oil and gas company, Naftogaz, which was UAH 21 billion orUS$2.6 billion, equivalent to 1.6% of GDP in 2011. A planned 50% hike in gas tariffs in April 2011 was negotiated down to 30% hike in two tranches in return for unspecific “offsetting measures” to keep the wider fiscal deficit at 3.5% of GDP. However, eventually, the tariffs were not hiked at all in 2011, widening the actual deficit to 4.3% of GDP. The result of all this is that the IMF have their foot firmly put down, and it will be hard to get it lifted again.

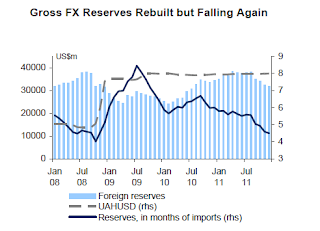

So one possibility is that the Ukraine government, seeing their approval ratings dropping, will consider the political costs of household gas tariff hikes to be too high, and not seriously pursue a renewed IMF deal, hoping that the cut in the current account deficit due to the lower gas import price plus any other investment commitments or payments which would arise from of a Russian gas deal will be enough to reduce pressure on reserves to a sustainable level. The Bank has spent nearly $7bn – or 20% – of its reserves since last August, and with reserves now approaching $30 billion this strategy is clearly becoming unsutanable.

There is, of course, another possibility, and that is that there is no Russia deal and no IMF deal. This could occur if the government baulks at both of the possibilities on the table: either selling a stake in the gas transit corridor to the Russians or raising household gas tariffs. Under this scenario the Ukraine government could follow in the footsteps of Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban which involves seeming to cooperate (in this case with both parties) but doing nothing, and in the meantime hope to muddle through – at least in this case till the elections in October. However, against the backdrop of falling reserves, a rising current account deficit and external funding markets which are closed to Ukraine, a sharp devaluation could become virtually unavoidable if there is neither a gas deal and nor a resumption of the IMF programme.

Following the decision of the ECB to introduce 3 year LTROs and the agreement on the terms of a second Greek bailout global risk sentiment has improved significantly in recent weeks, but it would be foolhardy to imagine that this situation will become permanent. Too many risk elements are still in play, and there are still far too many loose cannon floating around on the EU upper deck for vigilance to relax. But that is exactly what may happen, in which case, if disaster does strike in Ukraine, it will surely be disaster.

This post first appeared on my Roubini Global Economonitor Blog “Don’t Shoot The Messenger“.

Comments are closed.