The Latvian financial crisis

This is not what you think it is. And it is not what I intended to write about, either. I was going to write about Latvia as it is now, after the deepest recession in the world in 2008-9 and an excruciatingly painful front-loaded fiscal consolidation. Has it really recovered, or is it just marking time?

But in looking at Latvia now, I find myself drawn to its history. Latvia’s unusual response to the kicking it got in 2008 was because of its history. It had a deep recession 1991-3 and a severe financial crisis in 1995. These experiences undoubtedly coloured its response to the 2008-9 disaster. We should not assume that the harsh medicine Latvia swallowed in 2009-13 would either work or be appropriate elsewhere.

So, Latvia. For those who have never heard of it (apart from bad Eurovision songs), it is a tiny country sandwiched between Lithuania and Estonia, bordered on the East by Russia and Belarus and facing Sweden across the Baltic Sea. Here’s a map:

Although Latvia has an ancient pedigree, its present independence has been hard-won. It was the subject of constant territorial wars from the thirteenth century onwards, finally being incorporated into the Russian empire in 1710. After a long campaign it was granted independence from Russia in 1920, only to be seized and forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1940. It was invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany in 1941 then recovered by the Soviet Union in 1944-5. It was then brought under close Soviet control and progressively “Russified”: factories were built, farms collectivised and large numbers of Russian speakers relocated to operate them.

Latvia began a new quest for independence in the 1980s. The Latvian Supreme Council declared independence in May 1990: this was initially resisted by the Soviet Union but finally granted in August 1991. After independence, Latvia quickly became a member of the UN, the IMF and the World Trade Organsiation, and joined the European Free Trade Area in 1992. In 2004 it became a member of both the EU and Nato. It converted to the Euro in January 2014. <div >But its independence has not only been hard-won, it has been extremely painful. Immediately after independence Latvia set about the task of converting from a command economy to a market economy. The effect on the Latvian economy was harsh. Soviet-supported heavy industry entirely collapsed, as the website Latvian History explains:

In the Soviet period Latvia was the industrial center in the USSR. Soviets build a large amount of factories in Latvia and sent thousands of workers from whole union to Latvia. This caused mass immigration and downsize of Latvian majority. This leads to speculate that massive industrialization was intended to assimilate Latvian nation. Large industrial enterprises worked only for Soviet market and were associated with main company bodies in Moscow. Also they were deeply connected with the Soviet military complex and half of the civilian industrial production was actually used for military purposes. After the fall of USSR these factories could no more compete with free market and lost contact with state and Russian military. Large enterprises such as State Electronics Factory, Red Star, Alfa and others bankrupted. State officials done little to prevent whole industry collapsing. Today is still hard to answer could industry be saved and what should be done. However many say that it was impossible to save it. But the loss of large enterprises made a large amount of unemployed people.

Re-establishing private property rights also caused agricultural production to fall:

Reforms hit hard also on agriculture. In Soviet era all agricultural property was in state hands. Collective farming (kolkhoz) was the main subject in the country. When private property was established kolkhoz’s failed as the land was privatized. In Soviet times all farm land was sowed and farms were rich, now because of poor handling of private property land became poor and undeveloped.

And, of course, Latvian branches of Soviet-owned banks suddenly found themselves cut off from their parents. Latvia’s new central bank collected them all under its wing and allowed them to continue lending on a business-as-usual basis, largely unsupervised, while the Government decided on a privatisation strategy. Safely backed by the central bank, and accountable to no-one, they carried on lending to the collapsing industrial sector. Non-performing loans rose at an astonishing rate: an audit performed with the assistance of the Swiss government revealed NPLs of 25m Lat (about $250m).

In parallel with this, Latvia permitted uncontrolled creation of new, lightly regulated commercial banks. Unsurprisingly, banks proliferated: between 1991 and 1993 over 60 new banks were created. Some were “pocket banks” owned by state enterprises, some were created to raise deposits for on-lending to their owners, while others were solely intended to raise finance for specific functions: Olympija Bank, was created to fund the Latvian Olympic team. These banks grew very fast. By December 1994 85% of bank assets were in the new commercial banking sector. But the new banks, lacking adequate regulation or even – as it turned out – honest and competent management, were fragile and vulnerable to shocks.

In 1993 most of the former Soviet branches were sold to some of the largest of the new commercial banks. The remainder were consolidated under new management into a new state-owned savings bank, Unibank: the NPLs were removed from its balance sheet into a “bad bank” and replaced with government bonds.

In March 1995 the largest of the new commercial banks, Bank Baltija, collapsed, apparently due to lack of confidence after it was unable to provide the Bank of Latvia – or even its own auditors, Coopers & Lybrand – with accounts that complied with IASB standards. Bank Baltija was high-risk by any standards, expanding its deposits very fast by offering interest rates in excess of 90% when other lenders were offering a more restrained 14-20%. But no-one was paying attention to risky behaviour by banks. Consequently, when rumours started that Bank Baltija was in difficulties, there was a slow bank run not only on Bank Baltija but on other commercial banks too, most likely because of concerns that private deposit guarantees would turn out to be worthless.

The Bank of Latvia initially provided liquidity. But it soon became clear that providing liquidity was simply pouring money down the drain. Bank Baltija was deeply insolvent. Its negative net worth was estimated to be $320m, about 7% of Latvia’s projected 1995 GDP. Bailing this bank out was not an option: Latvia was running a fiscal deficit of about 3% of GDP, rather high for an economy in transition, and it was barely recovering after the deep recession caused by the post-Soviet restructuring. The bank had to be resolved.

Initially, the owners and managers suggested a merger with the Latvian Deposit Bank and Centra Bank. This may have been a delaying tactic to enable them to salt away Bank Baltija’s assets, principally via a Russian “pocket bank”, Intertek, incorporated in Moscow and apparently owned by Russian oil and energy interests. By the time Bank Baltija was declared insolvent in July 1995, over half of its assets had mysteriously disappeared. Eventually, it was taken over and restructured by the Bank of Latvia.

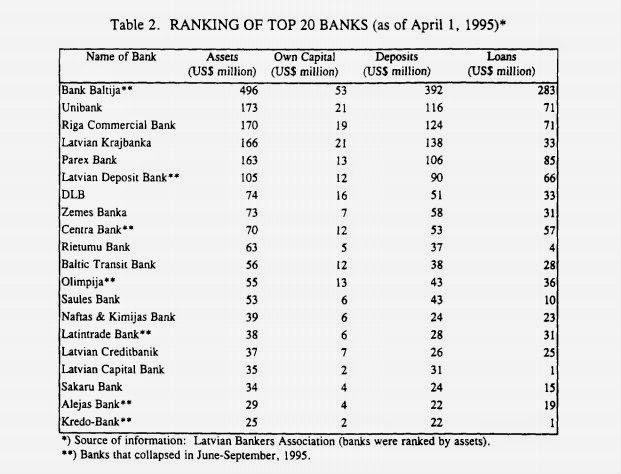

But it is just as well that the merger did not proceed. The Latvian Deposit Bank and Centra Bank also failed. In total, seven banks failed in the Latvian crisis:

Other banks also required liquidity support.

Alex Fleming and Sam Talley at the World Bank, in a fascinating paper (from which the above table is taken), drew five lessons from the Latvian crisis. I reproduce them in full here for reasons which will become apparent.

1. The banking systems of transitional countries are inevitably exposed to major strains and stresses, particularly during the first several years of the economic reform process. This is for three reasons:

- Restructuring and privatisations of state-owned enterprises limit their borrowing capacity and ability to service their debts. Privatisations are often a major part of reforms designed to liberalise a sclerotic economy, but eliminating state support for enterprises can pose serious risks to banks. This problem is as far as I know seldom if ever considered in the planning of economic reforms.

- Reduction in inflation due to major economic restructuring, which is usually accompanied by (sometimes deep) recession, reduces the ability of businesses and households to service their debts, again with potentially disastrous effects on banks.

- Economic liberalisation tends to result in largely privately-owned banking systems that lack adequate regulation, insurance or lender-of-last resort facilities. We would now call these “shadow banking” systems.

2. If banking systems are exposed to stress, the government must take strong actions to protect against this vulnerability. This means:

- establishing a sound legal framework for banking, developing effective regulatory and supervisory functions, and implementing good bank disclosure, accounting and auditing standards

- developing effective mechanisms for handling problem banks and closing insolvent banks promptly. The World Bank writers observe: “In Latvia, it was not just that Bank Baltija, the largest bank in the system, failed, but that when it was finally closed it was so deeply insolvent that the government essentially lost the option of bailing out this key bank in order to protect depositors and the payments system”. When a bank is failing, delay is costly.

3. State-owned banks can serve a useful function as “buffers” in a systemic crisis, as Unibank did in Latvia, provided they are well managed and are “relatively free from political influence”.Perhaps we should not be quite so quick to privatise everything, or to assume that only the private sector can run banks efficiently and effectively?

4. Supervisory authorities should look carefully at banks which are ‘outliers” in the banking system. “Banks that are expanding their assets or branch networks exceptionallv quickly, or banks that are offering particularly high deposit rates, should be subject to intense supervision. Activity in specific banks which is outside the norm may be an indicator of a problem in the bank concerned.”

5. Fraud, managerial incompetence and excessive risk-taking can have devastating effects on a banking system, particularly if they occur in the largest banks. The solutions to this are:

- Screen carefully those who want to work in banking

- Impose frequent thorough on-site examinations on all banks: allocate the best examiners to the banks that pose the greatest systemic risk

- Annual audits should be required for all banks regardless of size, and auditors must have a legal duty to report significant irregularities to supervisory authorities

- Where banks are in trouble and there is a hint of fraud, authorities should act decisively to deal with the banks AND those responsible for the problem.

Written in 1996, these are supposedly lessons for transitional economies. This is probably why they have been ignored. No-one imagined that the very same problems could occur – several orders of magnitude larger – in mature Western economies. But we now know better, don’t we?

The lessons from Latvia’s 1995 financial crisis resonate today as the Western world attempts to reinvent its dysfunctional banking system in the aftermath of the worst financial crisis since the 1930s. They seem eminently sensible: perhaps, if we had applied those lessons to developed as well as transitional countries, the course of history might have been very different…..

But there’s a problem. In the 2008-9 crisis, Latvia suffered more than any other country despite its extensive bank reforms after the 1995 crisis. Yet only one of its banks failed (Parex): the rest were bailed out by their foreign owners. So the question is, if Latvia’s banks were actually in better shape than those in other countries, why did Latvia suffer the worst recession in the world?

To be continued……

Riga, capital of Latvia. Photo credit: Wikipedia

Comments are closed.