By Paul De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji

A recent ECB household-wealth survey was interpreted by the media as evidence that poor Germans shouldn’t have to pay for southern Europe. This column takes a look at the numbers. Whilst it’s true that median German households are poor compared to their southern European counterparts, Germany itself is wealthy. Importantly, this wealth is very unequally distributed, but the issue of unequal distribution doesn’t feature much in the press. The debate in Germany creates an inaccurate perception among less wealthy Germans that transfers are unfair.

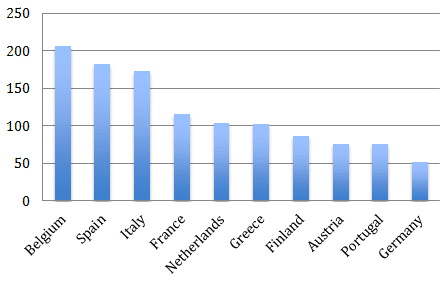

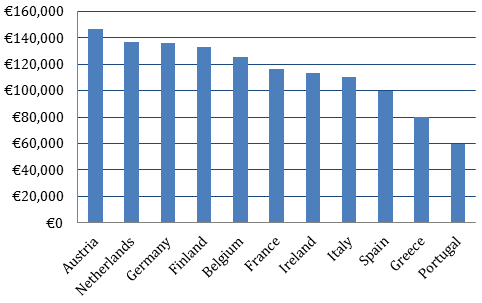

Rarely have statistics been misused so much for political purposes as when recently the ECB published the results of a survey of household wealth in the Eurozone countries (2013a).1 From this survey it appeared that the median German household had the lowest wealth of all Eurozone countries. Figure 1 summarises the main results for the most significant Eurozone countries.

Figure 1. Net wealth of median households (1000€)

Source: European Central Bank (2013).

From Figure 1 it appears that not only the median German household has the lowest wealth, but also that the differences within the Eurozone are enormous. The median households in countries like Belgium, Spain and Italy appear to be three to four times wealthier than the median German household. Even the median Greek household is twice as wealthy as the German one.

The publication of these numbers by the ECB quickly led many observers to conclude that it is unacceptable that the poor Germans have to pay for the rescue of the much richer Greeks, Spaniards and Portuguese (see, e.g., Wall Street Journal 2013, Financial Times 2013, Frankfurter Allgemeine2013).

Is this the right conclusion?

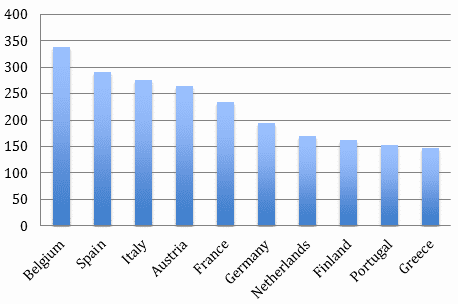

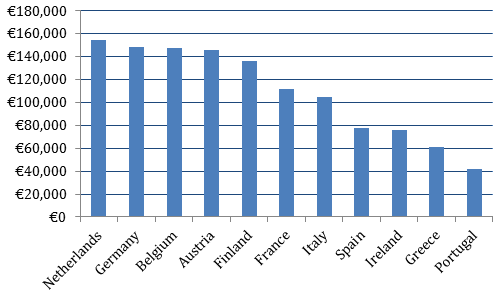

A first thing to note is that the ECB also published the mean net wealth of households in the Eurozone. Surprisingly, the mean household wealth numbers were not given much attention in the media, despite the fact that when compared with the median numbers they provide important information about the distribution of wealth in the different member countries. We show the mean wealth numbers in Figure 2. It is striking to find that the mean household wealth of Germany (approximately €200,000) is not the lowest of the Eurozone anymore.

Figure 2. Mean household net wealth (1000€)

Source: European Central Bank (2013).

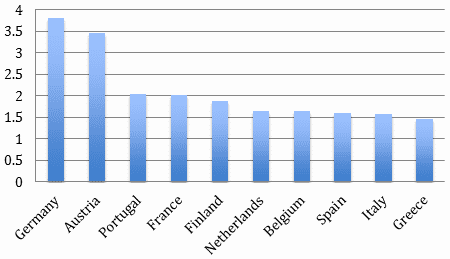

A comparison of the median and mean wealth reveals something about the distribution of wealth in each country. If the largest difference is between the mean and the median, the greater is the inequality in the distribution of wealth. It now appears that the difference is highest in Germany. We show this by presenting the ratios of the mean to the median for the different countries in Figure 3. In Germany the mean household wealth is almost four times larger than the median. In most other countries this ratio is between 1.5 and 2. Thus household wealth in Germany is concentrated in the richest households more so than in the other Eurozone countries. Put differently, there is a lot of household wealth in Germany but this is to be found mostly in the top of the wealth distribution.

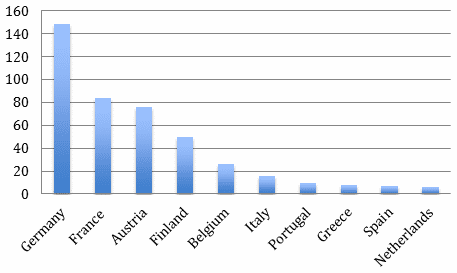

The inequality of the distribution of household wealth is made even more vivid by comparing the wealth owned by the top 20% of the income class to the wealth owned by the bottom 20% of the income class. This is shown in Figure 4. We find that in Germany the top 20% of the income class has 149 times more wealth than the bottom 20% of the income class. Judged by this criterion, Germany has the most unequal distribution of wealth in the Eurozone.

Figure 3. Mean/median

Figure 4. Wealth top 20% / wealth bottom 20%

Source: European Central Bank (2013b).

Wealth of households and wealth of nations

The next question that arises is whether household wealth is a good indicator of the wealth of a nation. A significant part of a nation’s wealth can be held by the government or the corporate sector and not by the household sector. If the question is to find out how much capacity Germany has to make transfers to other countries, a more comprehensive measure of wealth should be used. Such a more comprehensive measure of wealth is available. This is the total capital stock of a nation. This is a measure of the capacity of a nation to generate (together with human capital) an income stream.

We used available information on the capital stocks in OECD countries and updated this to 2012 (see Appendix for more information). We then computed the net capital stock per capita in the member countries of the Eurozone. We use two definitions. The first one is the domestic capital stock per capita (Figure 5). The second one is the sum of the domestic capital stock and the net international investment position vis-à-vis the rest of the world. We call this the total capital stock per capita (Figure 6). We find strikingly different results when compared with the household wealth figures.2

Figure 5. Domestic capital stock per capita (euro)

Source: authors’ own calculations, Eurostat and Database on Capital Stocks in OECD Countries, Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

Figure 6. Total capital stock per capita (euro)

Source: authors’ own calculations, Eurostat and Database on Capital Stocks in OECD Countries, Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

The most important difference is that the northern Eurozone countries are the wealthiest countries in the Eurozone. This conclusion can be made by looking at the domestic and the total capital stock numbers (Figures 5 and 6). When concentrating on the total capital stock (Figure 6), it appears that Germany belongs to the top two countries in terms of per capita wealth. In contrast the southern European countries have the lowest wealth. Wealth per capita is more than twice as high in northern European countries than in southern countries such as Greece and Portugal.

Conclusion

From this analysis it follows that it is misplaced to conclude from the ECB study that Germany is poor compared to some southern European countries and that therefore it is not reasonable to ask German taxpayers to financially support ‘richer’ southern countries (see e.g. Wall Street Journal 2013). The facts are that Germany is significantly richer than southern Eurozone countries like Spain, Greece and Portugal.

There does seem to be a problem of the distribution of wealth in Germany:

- First, wealth in Germany is highly concentrated in the upper part of the household-income distribution.

- Second, a large part of German wealth is not held by households and therefore must be held by the corporate sector or the government.

Thus while it is may not be reasonable to ask the ‘poor’ median German household to transfer resources to southern European countries, it may be more reasonable to make such demands on the richer part of the German households and the corporate sector. Put differently, the opposition in Germany to making transfers to the south finds its origin not in the low wealth of the country. The facts are that Germany is one of the wealthiest countries of the Eurozone. The problem is that this wealth is very unequally distributed in Germany, creating a perception among less wealthy Germans that these transfers are unfair.

References

European Central Bank, (2013a), “The Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey, Results from the First Wave”, Statistics Paper Series 2, April.

European Central Bank (2013b), “Statistical Tables to the Eurosystem Household Finance and Consumption Survey”.

Christophe Kamps (2005), “New Estimates of Government Net Capital Stocks in 22 OECD Countries 1960–2001”, IMF Staff Papers.

Financial Times (2013), “Poor Germans tire of bailing out Eurozone”.

Frankfurter Allgemeine (2013), “Reiche Zyprer”, arme Deutsche, 10 April.

The Wall Street Journal (2013), “Europe’s Poorest”, Look North, 10 April.

Appendix

We use the estimates of net domestic capital stock (1960-2001) from Kamps (2005). Net domestic capital is defined as the sum of government capital, private residential capital and private non-residential capital. The net refers to the fact that a depreciation rate is applied to the existing stock. Different depreciation rates are applied to different types of capital stock in order to extend the data to 2012 add the yearly gross fixed investment (2002-2012) to generate the total net domestic capital stock of each country in 2012. We apply a yearly depreciation rate in the period 2002-2012 of 3%.

In order to obtain the total net capital stock we add the net international investment position to the net domestic capital stock. For countries like Germany this the total net capital stock exceeds the domestic one as German has accumulates large current-account surpluses. The opposite is true for most southern Eurozone countries.

All the final values are adjusted to the price level of the 2012 euro.

1 The survey is based on a sample of 62000 households across 15 Eurozone countries

2 Note that we use per capita wealth numbers not wealth per household

This post was originally published at VoxEU.

Comments are closed.