Portugal Gradually Shuffles Its Way Up Towards The Front Of The Debt Queue

By Edward Hugh

Well, a weekend during which Greece seems to have been finally able to pass muster on its bond deal, while Mario Draghi has given the official “all clear” on the debt crisis seems to be as good a moment as any to have a look at where the country which many investors consider likely to be the next to enter the restructuring process is up to.

Speaking after last week’s meeting of the ECB’s governing council Mr Draghi said the recent three-year long-term refinancing operation (LTROs) had been an “unquestionable success” and had “removed tail risk from the environment” For the uninitiated “tail risk” is defined by Wikipedia as ”the risk of an asset or portfolio of assets moving more than 3 standard deviations from its current price in a probability density function. Such risk is often under-estimated using normal statistical methods for calculating the probability of changes in the price of financial assets”.

Now I’m not exactly sure whether a two percentage point shift in bond yields over a 12% starting point – or a movement of about 16% in two weeks – counts as tail risk in the technical sense, but it sure looks like it should do, and this is basically what just happened to Portugal.

Portuguese bond yields are rising as investors are busy putting cheap money from the European Central Bank to work elsewhere. The increase in 10-year borrowing costs by almost two percentage points in the past two weeks is stoking concern among investors that the nation will struggle to resume bond sales in 2013. Portugal has been unable to sell debt due in more than a year since it was given a 78 billion-euro ($102.8 billion) bailout in May 2011, following Greece and Ireland……Portugal’s 10-year yield was at 13.83 percent at 12:07 p.m. in London, up from 7.48 percent a year ago. The extra yield investors demand to own the nation’s bonds rather than Germany’s widened 1.1 percentage points to 12.04 percentage points since the ECB announced its program of three-year loans to banks on Dec. 8. Italy’s spread shrank 124 basis points to 3.2 percentage point, and Spain’s narrowed 53 basis points to 3.26.

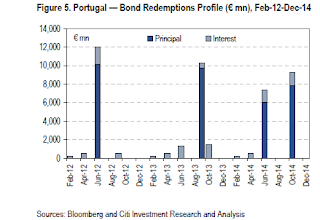

So why would people think that Portugal might be the next to need a second bailout? Well, what the Greek historian Thucydides would have called the efficient cause would be the fact that it has a 9.3 billion euro bond redemption due in September next year and the despite initial Troika hopes, the markets remain closed tighter than the lips of Angela Merkel were to the supposedly amorous advances of Silvio Berlusconi.

But the final (or underlying) cause which will send Portugal into a second bailout is the fact that the country has a high level of debt (both public and private) and a chronic growth problem which won’t simply be turned round by a bit of good will and a few “magic wand” structural reforms. So essentially the numbers just don’t add up.

So Just What Are The Numbers?

“Our baseline expectation remains that Portugal will be able to access markets late next year,” Abebe Aemro Selassie, who is taking over supervision of the IMF portion of the international bailout plan for Portugal, said yesterday in an interview with Bloomberg television. “This will not be easy.”

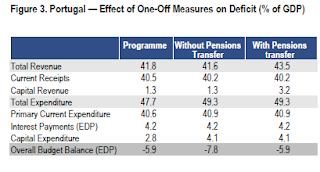

With interest rates on 10 year bonds up around 14% it certainly won’t be. According to the Troika calculations Portugal had sovereign debt of 102.7% of GDP in 2011, and a budget deficit of 5.9% broadly in line with the target laid down in its bailout package. Yet, despite the fact that the Portuguese reform programme was recently described by the WSJ (following the lead of the IMF) as being on track, the deficit numbers were, in fact, only saved by a last minute scramble which involved transferring funds (5.6 billion Euros or 1.9% of GDP) from the banking-sector pension system to the government social security one, in order to achieve what the IMF consider a short term accounting benefit. There were also questions raised as to whether this was not “short term gain for long term pain” in another sense, since the government has also to assume future liabilities for bank pensions, and several experts have queried whether these liabilities were transferred on a “fair value” basis, or whether indeed some sort of disguised longer term (in the short term the bank balance sheets take a hit) subsidy to the banking system was not in fact indirectly provided.

In their second review of the programme (published in December) the IMF said the following: “Staff questions both the timing of the transfer and the appropriateness of in effect using an accounting technique to mask the true fiscal position”. That is to say the Fund has a double role here – to talk the efforts of the Portuguese administration up before the world’s press, and to try and keep the politicians in line in the background.

So achieving last years target was not easy (see above chart which comes from an excellent research report from Citi analyst Jürgen Michels and his team), with the day only being saved was by a one-off transfer, a technicality which means that this years deficit reduction will effectively be from a real base of 7.8% of GDP (5.9% + 1.9%) to 4.5% (or 3.3 percentage points), which is significantly larger than the 2011 reduction which was really from 9.1% in 2010 to only 7.8% (or 1.3 percentage points – ie the fiscal “effort” in 2012 will be two and a half times as big as the 2011 one).

Without the accounting “fudge” revenue would have come in significantly under target, and this highlights one of the big problems in all the deficit reduction programmes that are currently in place on Europe’s periphery, namely that the economic contraction associated with austerity programmes (in uncompetitive economies) produces a severe fall in revenue, one which is not necessarily associated in linear fashion with the output fall itself. For example, a 10% fall in retail sales demand may produce a much more dramatic fall in profits, which means that tax income from profits can be almost wiped out. This is one of the problems the Greeks have been constantly up against, and was surely partly behind last years big Spanish budget target “miss”, and while many stress that programme implementation issues are fewer and farther between in Portugal than in Greece they are hardly negligible looking at the country’s track record, so the administration will be permanently struggling to meet 2102 revenue targets.

Non-evident Non-negligible Liabilities

As well as revenue shortfalls, government expenditure also overshot, largely due to greater than planned capital expenditure. The reasons for the non-compliance with expectations on the capital spending side are interesting, since they mainly derive from the needs of Portugal’s state-owned companies (SOEs) and transfers made to Public Private Partnerships (PPPs), which surely form an important part of the programme slippage risk.

Anyone who has recently read my recent post on the true level of Spanish debt should not be the least surprised to find that similar issues exist in Portugal (for explanations of methodology see the Spanish post). As in the Spanish case the government provided guarantees for SOEs, so it has contingent liabilities and might be forced at some point to take over the debt. According to IMF estimates, explicit guarantees to Portuguese SOEs (including those outside general government accounts) represented anywhere between 10% and 15% of GDP in mid-2011.

Then there are the PPPs. These are especially important in Portugal, and the value of the government’s ultimate exposure may be something like 14% of GDP. Such partnerships have been popular politically since they have the accounting advantage for governments that, as the private sector holds the debt and the state simply services it, the outstanding quantity doesn’t count as state debt for Eurostat EDP purposes. Indeed such schemes have even been marketed to government agencies on just these grounds, as I pointed out in an early post on the topic – Just What Is The Real Level Of Government Debt In Europe? (February 2010). PPPs are often used to finance infrastructure programmes, with the government paying a charge to use the infrastructure until final ownership is assumed at the end of a defined period. In the Portuguese case such “rents” amount to about 1% of GDP annually.

Then, naturally, there are the accumulated unpaid bills. According to Eurostat data Portugal had 8.8 billion Euros worth at the end of September last year, or around 5% of GDP, although note that some of this will be normal trade credit, so the Portuguese government’s own estimate of 3.5% of GDP which should be counted as debt may not be that far from the mark.

Also, banks need recapitalising, and the IMF estimate that the banking system will need funding to the tune of about 4.7% of GDP in 2012 alone.

Growth Beyond The Bounds Of Avarice

So the 2012 deficit objective is challenging, and the risks to the debt path are not negligible, but the main issue determining where Portugal goes from here is not whether or not the country will be able to go back to the markets at the end of next year, but whether or not the country’s economy is able to make the growth leap assumed in the IMF debt forecasts.

According to the latest set of projections, the IMF anticipate a GDP contraction of 3% in 2012, to be followed by a return to growth at a rate of 0.7% in 2013. Crucially though, the Fund anticipates a growth rate of 2% or more on a more or less constant basis from 2014 onwards. This assumption is based on the impact of the proposed structural reforms which are more or less similar in all the programme countries – namely reform of the public administration to reduce the size and cost of the public sector, product market reforms to improve competitiveness (in this case especially in the telecommunications sector), and labour market reforms.

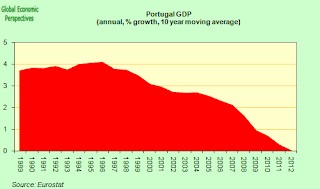

Now I have no doubt at all that most of these reforms are badly needed, I just doubt they will have the kind of “growth surge” impact that is being widely assumed. The Portuguese long term GDP trend has been heading strongly downwards in a most notable way for a decade and a half now, and turning this around will involve a lot stronger force than seems to be being anticipated. In addition, Portugal has an ageing workforce which will surely be a growth rate negative, and the current deep economic recession is leading to substantial human capital loss, as young people leave to find work and a better life elsewhere. In fact these kinds of negative feedback loop are simply not considered in the kinds of growth model the EU and the IMF use, but are very important in determining the future path of an economy, as I try to argue in this presentation I recently gave in Riga (referring to the Latvian case).

It’s not that I think the growth rates being offered are too optimistic, I think they are based on a theoretical model which is by-and-large out of date.

The IMF themselves recognise that none of this is going to be easy, when they say:

“Restoring competitiveness will require improvements in productivity accompanied by an internal devaluation. As productivity gains will materialize only gradually, the program will continue to focus on measures to lower input costs, increase the competitiveness of domestic production, and allow for a reduction in non-tradable prices…..In particular, significant adjustment in wages is needed in the short run, before reforms enhance productivity over time. In this regard, public sector wages cuts, extension of working hours, and the decision to redesign the extension of collective wage agreements and not to grant automatic extensions during 2012 are welcome.”.

Following a pattern previously established in Latvia, Hungary and Greece, public sector wages and pensions are being reduced – principally by means of a 2-year suspension of the extra two (summer and xmas) monthly payments of both wages and pensions (the IMF estimate that this is equivalent to a 12-percent average cut), but while this reduces pressure on public finance, the mechanism via which this would produce an increase in competitiveness in the tradeables/export sector is far from clear, to me at least. Perhaps it is worth noting at this point, that Hungary has implemented most of the measures being proposed in Portugal without visible impact on the country’s growth rate.

The only measure which it seems to me would start to lower wage costs in the private sector (as opposed to the improved productivity path, which the fund itself admits will be slow) would come from a measure to decentralise wage agreements in the way the new Spanish law allows, and let wages in the private sector fall steadily. But this would of course be deflationary, and hence would have its own impact on debt sustainability. In fact IMF forecasts are based on CPI inflation of around 1.5% annually between 2013 and 2016, so they themselves are hardly expecting any serious deflation, or even the relatively mild kind which the country experienced in 2009 (-0.9%).

So it looks to me pretty much like the country is facing a long period of adjustment (possibly over a decade) just like its Spanish counterpart, and it is unrealistic to think it won’t need support throughout this period. Simply put, the difficulty of implementing a correction of the magnitude Portugal needs within the framework of a common currency has been greatly underappreciated by policymakers right from the outset.

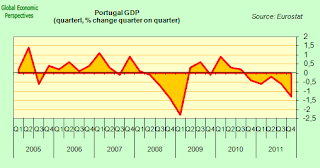

In Recession Now

Portugal’s gross domestic product shrank 2.8% in the fourth quarter on an annual basis, and fell 1.3% from the third quarter, according to the latest data from the National Statistics Institute. For 2011 as a whole, the economy contracted 1.6%, as compared with a 1.4% growth in 2010. Last year, exports rose 7.4%.

Growth got worse as the year progressed, showing the country is being hit by the slowdown in other countries in Europe and elsewhere. With domestic demand falling, and government consumption being cut back the country is now largely dependent on exports for growth, but with the country’s largest export market, Spain, also undergoing its own austerity program this growth is getting harder to come by.

The chart above, which only shows data up to the end of September, makes plain how exports had surged following the ending of the first European recession, offsetting the negative trend in household demand.

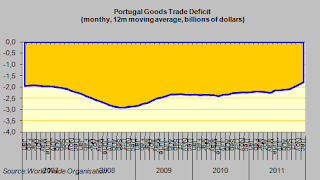

But the latest data show that while net trade was a positive element in fourth quarter GDP, this was largely the result of a very sharp fall in imports. Year on year exports were up 5.8%, while imports fell by a whopping 13.5%. We don’t have official data from the statistics office on quarter by quarter changes in exports, but the data we do have suggests they stagnated when compared to the third, following a pattern generally seen across Europe. Despite the almost total dependence of the economy on exports now for growth, the country still runs a goods trade deficit.

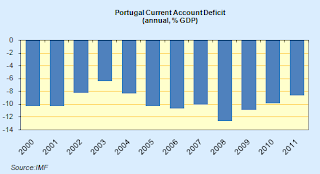

And while both this and the current account deficit have improved over the last year, the rate has been painfully slow, indeed the IMF is still forecasting a CA deficit all the way through to 2016 (and presumably beyond) with a 5% deficit in 2013 and still a 2.8% one in 2016. To put this in perspective, countries in Eastern Europe like Latvia and Hungary who have been through these corrections already now run current account surpluses, and they are still a long way from being out of the woods.

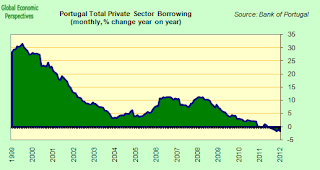

Naturally, the Eastern countries are not direct beneficiaries of the ECB liquidity LTRO programmes, but while these make it easier for banks to meet their wholesale money needs, and governments to sell T bills and other instruments to banks, there is little sign they are likely to do much to help domestic credit till the correction is well advanced, and that, as we have seen may need many years.

Sustainable Or Not Sustainable?

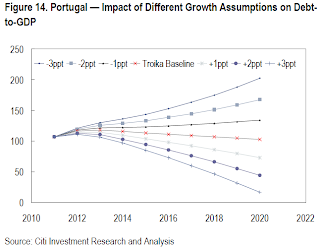

Now all of this is relatively important, since debt dynamics are (other things being equal) quite dependent on economic growth rates. Just how dependent can be seen from the chart below, prepared by Jürgen Michels and his team at Citi. As can be easily seen, it only needs a growth rate of one percentage point on average below the troika baseline scenario for debt to be sent uncontrollably upwards, and the more the average growth rate deviates downwards the more rapidly debt rises.

Now there are three factors which basically determine the debt trajectory – GDP growth, interest rates on the debt and inflation. The second of these can be more-or-less determined by the rescue programme, but inflation is the catch 22, since if inflation falls to very low or negative levels this helps send debt up, while if it doesn’t the country can’t regain export competitiveness, and there doesn’t seem to be any easy way round this, which is why I can’t see the reason for policymakers being so adamant Portugal doesn’t need restructuring.

In fact this is the conclusion the Citi analysts have come to, since they are now arguing that Portugal will need a 50% PSI this year (you remember those, don’t you, from recent Greece experience).

In earlier assessments of its debt position, we argued that Portugal would not be able to move on to a viable fiscal path without a haircut of 35% by the end of 2012 or in 2013. While we acknowledge that Portugal is in many aspects different from Greece, we now conclude that the size of the haircut will need to be higher, to the tune of 50%, most likely taking the form of a reduction in the debt held by the private sector.

If done in 2012, a 50% haircut in the nominal value of Portuguese government debt would help to cap the peak in the debt-to-GDP ratio at around 113% in 2015. Hence, in our scenario, Portugal will need around €70bn extra funding from the Troika (plus sweeteners for the PSI) in order to close the funding gap until the end of 2015.

The Citi team argue the restructuring is needed simply to keep Portugal free from the need to go back to the markets before 2015, but I would argue the case on the grounds of trying to recover debt sustainability. It is important to remember that Greek sovereign debt may well be lower than the Greek equivalent, but Portugal has a far higher level of private debt, and this is not sustainable and will need writing down through the banking system to some extent, and the banks will continue to need help from the sovereign in doing this. While Portugal’s private sector debt is near 200% of GDP, the Greek equivalent is only something like 120%.

Naturally, since Greece is only headed for 120% debt to GDP in 2020, but I think almost no one believes this level is sustainable, and it is only out of political correctness towards Mario Monti (whose countries debt nudged just above the 120% level in 2011) that anyone even vaguely genuflects in the direction of making believe it is.

So action will need to be taken, and realism does need to come back into policymaking. Maybe it sounds good to say that Portugal’s programme is on track, but it only got back on track after 1.9% of GDP was paid over from the pension fund. Implementation risks may be less in Portugal than in Greece, but that isn’t saying much, and they are certainly considerably higher than “non negligible”. Also, and as I keep saying time and again, the risk to this whole LTRO funded slow-debt-dialysis on the periphery is most certainly a political one – one of populations being “driven mad” by all the austerity and lack of hope (think Hungary).

Despite Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho’s assurances that Portugal won’t follow Spain in seeking to loosen its deficit bonds in 2012, only last week Antonio Seguro, leader of the Socialist Party that secured Portugal’s bailout program last May, told the Troika inspection team that the country needed more time to hit the fiscal goals set under the loan.

“We affirmed our conviction that it is desirable that Portugal gets at least another year to consolidate its public accounts,” he told journalists, citing the need to turn around an economy that is tipped to shrink 3 percent this year.

Obviously, these programmes do not win votes for the government implementing them, and one party can seek to gain advantage over the other in electoral arithmetic by opposing them – Spain’s socialist PSOE, for example, now oppose the new labour market reform introduced in that country, only weeks after coming out of office. And even the wage reductions are only seen as temporary, a way to reduce expenditure, and not as part of an internal devaluation process, in which context it is interesting to note that Romania’s President, President Traian Basescu, has just said that that country’s wage adjustment programme should be reversed, with salaries in the public sector being raised back to their pre-crisis level as of June 1, even though Finance Minister Bogdan Dragoi has just said he thinks the country has probably just re-entered recession.

Naturally austerity isn’t popular, and evidently it doesn’t work as intended, but then this was already known before we started on this course, so it isn’t really a surprise. But what alternative do the Euro Area’s imprisoned periphery have, since if they leave the currency and default on their debts they will be in a real mess, and if they stay they are in a real mess too? Obviously, the Euro Area countries could have a shotgun wedding, and pool debts, run a current account surplus and become a second Japan. But where exactly is Japan headed? No easy answers here, and even harder ones coming up further down the line.

This post first appeared on my Roubini Global EconoMonitor Blog “Don’t Shoot The Messenger“.

All of the periphery could do much better by defaulting on the odious debts and start again outside the euro. Iceland has shown it is possible and probably practical. The problem is that the core nations and the US banks will have to write hundreds of billions off and pay out hundreds of billions in CDS payouts. So the banking crisis is not over.

I think you’re right David. But first we have to get rid of this caste of politicians that are keeping us under the tyranny of Germany. It’ll eventually happen in the end, but in the meantime how much damage will we make to ourselves?

I am in the UK so we can devalue the pound to help take the strain, but we all really need capital controls, whether we are in the euro core or periphery or outside like the UK. This would have stopped the contagion, yet EU rules forbid capital controls.

My concerns are with the citizens of the periphery not the banks. Punishing the citizenry to save the banks will result in significant poverty and revolution. Bankers end up against the wall facing firing squads in these circumstances.

The EU has to be changed or abandoned if it doesn’t serve to its purpose: improve the living standards of the europeans. Politicians are questioning everything – including the Schengen treaty that the UK hasn’t signed – but the so called ‘economic freedom’. Freedom for whom? The banking sector is out of control and politicians are just puppets in its hands.

If the situation keeps worsening, we face more and more social conflicts which clearly show that we’re going backwards in terms of social progress. What’s the use of this European Union then?