Spain: The recession may be ending but the crisis continues

By Edward Hugh

What follows is an interview I did over the summer with the Madrid based publication The Local.

Let’s start with the basics: what are Spain’s current economic problems?

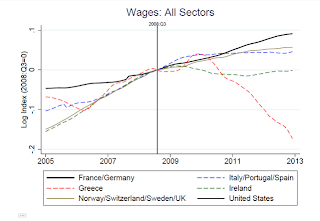

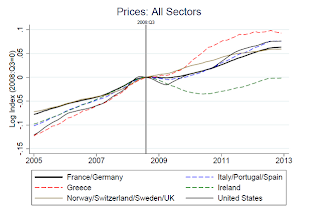

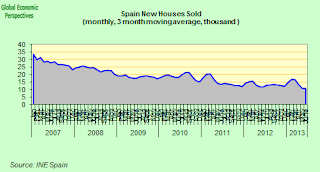

Spain’s economic problems are a knock-on effect of the end of Spain’s property boom. The collapse of the property market led to a drop in incomes, depressed demand for goods and — slightly — lower wages.

At the same time, apart from property prices haven’t come down.

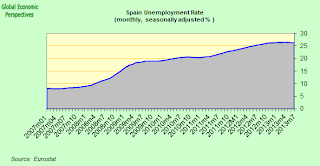

In addition over one adult in four isn’t working.

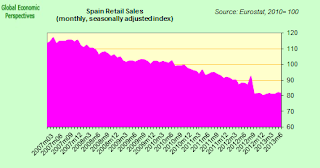

So consumption is steadily falling.

On top of that we have a debt overhang — which means it is difficult for Spain to borrow. Larger companies are struggling to get credit so they are delaying payments to smaller suppliers, which means smaller companies are finding it harder to get money. It’s a vicious cycle.

We are also seeing imbalances within Europe with the Germans doing ‘well’ and young Spaniards leaving the country to work elsewhere.

And how has the Popular Party (PP) government led by Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy tackled these problems?

One of the main objectives has been to avoid a financial rescue from the European Union. This was important for a number of reasons.

National pride was definitely one factor. Also, it is unlikely any Spanish government could have survived a bailout. Then there is the fact that Europe would have had a greater say in how the Spanish economy operated if a bailout had taken place. The EU would have been telling Spain which taxes to raise or lower, for example, or how to go about pension reform.

How do you rate the government’s attempts to cut spending?

At the end of the day, this government is made up of ‘middle of the road politicians’ and they are basically economically liberal. Which means they would like to see less government. So if the deficit hasn’t come down very far it hasn’t been for want of trying.

I would probably have to say their least recognized achievement has been their attempt to reform the public administration. This hasn’t been easy for the PP as some of the areas where the party has a lot of support are also places where there is not a lot of industry, and where government is a big employer. This being said Spain still had the biggest deficit in the EU last year (government spending exceeded tax revenue by 10.6 percent).

In addition, reform of the financial sector still has a long way to go as well because while there is increased liquidity in the system, more recapitalization is constantly required as the high unemployment and low demand for products means more bad loans are created with each passing day.

Recently, Spain’s Economy Minister Luis de Guindos asserted the recession may be over. He didn’t mention the crisis though.

That’s an important distinction. Luis de Guindos is an intelligent man and recognizes that while the crisis is ongoing, recessions are a normal part of the business cycle. Spain’s second recession since the crisis began could well be over.

And yes, we could well see two, or three, or even four quarters of weak economic growth but this is just part of the cycle. Indeed, our double-dip recession could eventually turn into a triple-dip one. This is because none of the underlying problems have been adequately addressed.

We were told house prices would bottom out with the creation of a bad bank, but they are still falling. There is probably some way to go still, maybe two or three more years of falling prices. The organization charged with handling failed banks’ property assets, the “bad bank” Sareb, isn’t operating very well either. Sales are very low and the costs for potential buyers from Sareb is too expensive as the organization doesn’t have depositors and has to make deals with other banks to give mortgages which end up making interest costs too expensive to make the purchase attractive.

And even while some of the old imbalances are adjusting new ones are being created since young people are now leaving Spain to work elsewhere in ever greater numbers. We don’t know exactly how many are leaving because Spain’s electoral roll doesn’t keep accurate track of where native Spaniards are living and working. What we do know is that last year Spain’s population fell for the first time in modern history, and that it will continue to fall as far ahead as the eye can see. A turning point of some kind has been passed.

What do you make of the spate of claims the crisis is over?

I believe these predictions play to two audiences. The first issue is a confidence issue. Politicians would like to give the impression to the Spanish people that the crisis is ending to encourage them to spend.

At the same time, Prime Minister Rajoy is fighting for his political survival. One of the likely consequences of the current lack of government credibility, in my opinion, is that Spain could – in time – become effectively ungovernable in a way which has become common in other southern European countries. Fresh elections are unlikely in the short run, but when they do come there is unlikely to be a clear majority party, the outcome is likely to be fragmented, and indeed the Catalans want a vote on whether to leave.

The (opposition socialist) PSOE party continues to have a huge credibility problem following the fiasco of the Zapatero government. They are currently polling at very low levels (21.6 percent according to a July poll run by Metroscopia).

It’s also very hard to imagine a political party in Spain making an alliance with Catalonia’s ruling CiU party given there is an independence referendum in the pipeline.

So what does the term crisis actually mean after five years?

My feeling is that it’s totally unrealistic to expect a ‘return to the old reality’. We are now in a change of paradigm process.

We all need to change our expectations and find ways to live with the new situation, since whether we like it or not we will have to. There is no quick fix – these have all been tried and failed – and Spain is now condemned to going through a painful long-term shift. The country will have to deal with its legacy debt.

Personally, I think the International Monetary Fund could have played a more important role. It could have acted as a kind of referee between Spain and the European Central Bank (ECB) and the EU, coaxing the country into adopting more fundamental changes. It could have pushed for the ”front loading” of the deep reforms the country needs (especially the much needed internal devaluation) coaxing the country into making changes at a time when the population was still receptive. But unfortunately even though the Fund is now trying to recover lost ground, most of the principal social actors turn a deaf ear. No one wants to hear more about harsh sacrifices, they only want “sweet words” about a looming recovery and regeneration.

In addition I believe the IMF is now increasingly trying to distance instance from Europe because it has become tired of playing the part of public relations officer for what are effectively EU-lead programmes. It is clear from the Greek case – and the recent IMF “mea culpa” – that this way of doing things doesn’t work. Further, non-European members of the Fund like Brazil, China and India are now increasingly pressuring the organisation to stop molly coddling Europe’s leaders. Look, for example, at how little money is being offered to Egypt and how much has been spent on Greece.

But what this means is that the organisation is now unlikely to play the role it once could have.

To what extent is Spain responsible for its crisis, and to to what degree are international circumstances to blame?

When the Euro was rolled out, the single currency idea clearly wasn’t thought through well enough. The EU leaders didn’t envisage the problems that have arisen.

Another part of the problem lies in an idea that existed in Europe before the crisis — this was the idea that all countries all had equal levels of risk. And this clearly wasn’t true. So to some extent the EU itself needs to assume responsibility.

But on the Spanish side, it’s obvious the political parties were up to their necks in fomenting the boom by letting regional savings banks keep lending money, and by allowing builders to keep building.

During the building boom, many Spaniards also became property speculators in their own right, buying more houses than they really needed. As the saying goes, ”When the music plays you have to dance”.

Comments are closed.