Spain and the Owl Of Minerva

By Edward Hugh

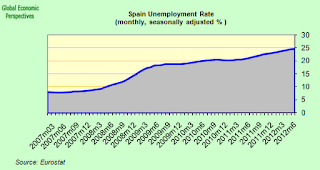

Last week was the fifth anniversary of the outbreak of the global financial crisis. Not uncoincidentally it was also the fifth anniversary of continually rising unemployment in Spain , since it was in early summer 2007 that seasonally adjusted Spanish unemployment embarked on its steady upward path. And after it started climbing, naturally it hasn’t stopped since. Indeed we seem to have at least another year of growing unemployment before us, maybe more.

Anyway, as if to celebrate this uncanny anniversary the Spanish government has decided to take the bold step of officially requesting an EU loan to recapitalise the country’s banking system. In addition, part of the money will be used to set up some form of bad bank with the objective of cleaning up some of the toxic property and other assets off the bank balance sheets. Smart moves both of them. Pity the people responsible weren’t prepared to accept the need to do this five years ago, when unemployment was only running at 8%, and when the economy and Spain’s citizens were better placed to accept the kind of burdens that are now about to be imposed upon them.

Just to round the commemorations off, in the August edition of their monthly bulletin the ECB finally let out that dirty little secret than every insider in the know has already discounted. The Bank have finally accepted that the much heralded Spanish labour reform isn’t going to work. At least not as planned. As the Financial Times put it, the Spanish labour market reform approved in February was “far-reaching and comprehensive” but came too late, the ECB implied, saying it “could have proved very beneficial” in avoiding job cuts if the measure had been passed some years ago.

Exactly. But once we recognise this point, isn’t that rather leaving the Spanish economy adrift in stormy seas without a rudder? Simply cutting the deficit back and cleaning up bank balance sheets won’t get the economy back to growth.

Indeed this habit of continually getting behind the curve, and trying vainly now that the economy is spiralling almost out of control to introduce measures which should have been brought in a decade ago extends well beyond the issue of labour reform. Take reducing the generosity of unemployment benefits. This is also something that should have been done years ago, since the two year allotment really did encourage people to refrain from actively seeking work in times of relatively full employment. But cutting benefits now, as the Rajoy government has just done, when unemployment stands at 25% and rising seems insensitive and even cruel. A government’s job is to introduce policies to create employment, not to cut benefits going to those who cannot find work in an environment where total employment is falling and has been doing so for five years. Quite frankly, if cuts have to be made, better to reduce pensions, but that is political dynamite, so it doesn’t happen.

Again, reducing the fiscal advantages of home ownership made mountains of sense during the years of the property bubble, but it didn’t happen. Now, with around two million housing units (between finished and uncompleted) needing to be found purchasers removing tax benefits on mortgages, increasing VAT rates on property transactions and raising the local property taxes – all of which make buying a homea lot less desirable – looks very much like trying to shoot yourself in the foot. There is a lot of merit behind the desire to stabilise Spain’s public accounts, but shouldn’t we also try to remember why the country has this crisis in the first place?

Anyway, having recognised that the labour reform comes to late to really change course decisively this deep into the crisis – something incidentally which we much maligned macroeconomists have been arguing all along – what does the ECB propose to supplement it? Well, according to the bulletin “countries with high unemployment also needed to abolish wage indexation, relax job protection and cut minimum wages.” Indeed the bank went beyond its usual practice of avoiding country specific commentaries to issue a direct prescription, saying it expected a “strong decline” in wages in Greece and Spain, countries which have the highest levels of youth unemployment in the eurozone, with more than 40 per cent of under-25-year-olds in the labour force out of work.

This strong decline in wages does not, mark you, form part of the kind of “internal devaluation” some of us have been arguing in favour of for some years now, whereby a battery of measures are introduced to try and bring down both prices and wages at one and the same time. Not at all. July inflation in Spain was running at 2.2% compared to 1.7% in Germany. Prices in Spain are going up, largely due to all those tax increases laid down in the adjustment measures. Annual inflation will probably surge by around two percentage points in September as the new consumption tax rates fall into place. So it is only wages which are likely to be coming down, and this makes it all feel much more like 1930s type wage deflation than the sort of internal devaluation that has been being advocated (see my January 2009 piece “The Long And Difficult Road To Wage Cuts As An Alternative To Devaluation” as a harbinger of all this).

Well, if you let things go to hell for the best part of five years, naturally the patient is in a poor state and in need of radical surgery. I won’t say “I hope they know what they are doing,” since I am pretty sure they don’t. Perhaps I would rather say I hope Mariano Rajoy knows what he is letting himself in for when he asks for help from the ECB.

Talking of which, and turning to another of the “troubled” countries, Italy, I see Finance Minister Vittorio Grilli has come out today and confirmed two issues I was conjecturing about in my blog post only yesterday. In the first place he admitted in an interview in the newspaper La Repubblica that it was unlikely the country would meet this years deficit target due to the depth of the recession, and in the second one he confirmed my fear that getting agreement to ask for EU help would be much more difficult than Mario Monti recognised during the press conference he held with Mariano Rajoy at Spain’s Moncloa Palace. Italy plans to wait for the ECB to act, and see what the measures look like, despite the fact that Mario Draghi has made it quite clear he will only do so after a request for assistance goes to the EU.

So instead of preparing a “battery of measures” to go to the root of Italy’s problems it looks like we what we may well face is protracted debate about how to avoid making any kind of formal request. The latest idea to surface is that of trying to get ECB agreement for the Cassa Depositi e Prestiti, a state-financing agency controlled by the Treasury and managing some €220bn in postal savings deposits, to be allowed to use its banking licence to secure loans from the central bank in order to explicitly buy government debt. As the saying goes, this one can run and run.

Which all brings me to the main point I have been thinking about all weekend, which is why it is that policymakers find it so incredibly hard to see situations coming, and to take corrective action before the train crash occurs?

“One more word about giving instruction as to what the world ought to be. Philosophy in any case always comes on the scene too late to give it… When philosophy paints its gloomy picture then a form of life has grown old. It cannot be rejuvenated by the gloomy picture, but only understood. Only when the dusk starts to fall does the owl of Minerva spread its wings and fly”.

-G.W.F. Hegel, Preface to the Philosophy of Right

This post first appeared on my Roubini Global Economonitor Blog “Don’t Shoot The Messenger“.

Comments are closed.