Much Ado About Nothing

By Niels Jensen

The Absolute Return Letter, July 2013

“Politics is show business for ugly people.”

Sir Bob Geldof

“Italy’s Berlusconi was sentenced to 7 years in prison for having frequented an underage prostitute and for abuse of office, as he helped the young lady out of prison claiming (falsely) that she was the niece of a former Arab leader. Berlusconi will appeal the verdict and the appeal has suspensive effect. At the same time, he is about to run out of appeal possibilities in a conviction for tax fraud, and that one is in fact far more serious.

If there is still anybody who is uncertain that Berlusconi’s real political intentions are to keep himself out of jail, they only need to look at his party’s response to the judgment. PdL has threatened to topple the government – without actually specifying why. In return, Berlusconi made it clear that he would find it appropriate if President Napolitano appointed him senator for life. It would confer life-long immunity upon him.

It is entertaining, but not exactly what Italy needs. There is a more acute problem which threatens to cause unrest. According to the Financial Times (and I have previously referred to the same story in 2012), there are clear signs that Italy has lost large amounts of money on derivatives positions, seemingly intended to conceal the real state of government finances. Worse yet, the story seems also to point out that Italy falsified the budget deficit leading up to the introduction of the Euro.”

Political incompetence

So writes Kim Asger Olsen of Origo Asset Management in one of his recent missives (you can find his work here). Kim is an astute observer of political and economic events, and I can only agree that Italian politics are high on entertainment value but low on quality. Having said that, it would be wrong to assume that Italy is the only country mastering the art of delivering such supreme political talent. All over the world we are confronted with political leaders who seem to care more about their own longevity than anything else.

A simple yet powerful example: Even at the best of times politicians like to run fiscal deficits as spending buys votes – Gordon Brown being the best example of fiscal irresponsibility that I can think of; however, it doesn’t stop there. Knowing very well that voters prefer transfer payments over more productive spending such as infrastructure investments, political leaders of all colours willingly deliver, even if it is plain wrong. Prostitution knows no boundaries.

Allow me to illustrate my point with a few numbers. The multiplier on transfer payments is estimated to be c. 0.85, i.e. the impact on GDP for each $1 of transfer payments is about $0.85[1]. Meanwhile, the multiplier on infrastructure spending can be as high as 3:1 or even 4:1. Say for argument’s sake that our government decides to build a new airport. For every $1 spent by the government, the private sector usually invests $2 or even $3 alongside the government, meaning that as much as $4 will be pumped into the economy for every $1 of public spending, creating many more jobs than the $1 of transfer payments does. Yet the buffoons running the asylum don’t seem to get it. Look at chart 1 below as to what has happened to U.S. infrastructure spending on Obama’s watch. Sadly, the U.K. story isn’t much different.

Chart 1: U.S. public construction spending (% of GDP)

Source: Joe Weisenthal, Businessinsider.com

Central bankers are getting annoyed

The growing presence of political incompetence is beginning to annoy the world’s central bankers who are effectively left to clean up the mess resulting from the ineffectiveness of our political leaders. In its 83rd annual report published recently, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) was uncharacteristically critical in its verdict. Jaime Caruana, General Manager of BIS, delivered the following broadside at the bank’s general meeting on 23 June:

“[Easy] financial conditions can do only so much to revitalise long-term growth when balance sheets are impaired and resources are misallocated on a large scale. In many advanced economies, household debt remains very high, as does non-financial corporate debt. With households and firms focused on reducing their debt, a low price for new credit is not terribly relevant for spending. Indeed, many large corporations are using cheap bond funding to lengthen the duration of their liabilities instead of investing in new production capacity. It does not matter how attractive the authorities make it to lend and borrow – households and firms focused on balance sheet repair will not add to their debt, nor should they.”

A little bit later in his speech he turned the screw a notch or two:

“Government attempts at fiscal consolidation need to be more ambitious. Average headline deficits in the major advanced economies have narrowed by about 3½ percentage points. This is broadly in line with previous episodes of fiscal adjustment, but it is not sufficient to bring public debt back to a sustainable path. In many cases, government debt is rising further, not withstanding record low servicing costs. Very low long-term interest rates are making government spending look cheap. But the belief that governments do not face a solvency constraint is a dangerous illusion. Bond investors can and do punish governments hard and fast when they believe that fiscal trajectories have become unsustainable.”

A clear warning if there ever was one. BIS has a point. Most governments have talked the talk but not yet walked the walk. Austerity has become a buzz word but few have actually delivered anything just vaguely resembling balanced budgets. The chart below, which I found in BIS’ annual report, does a good job in terms of illustrating the debt trends since pre-crisis levels in 2007 (chart 2).

Chart 2: Change in debt, 2007-12 (% of GDP)

Source: Bank for International Settlements, 83rd Annual Report, 2012-13

BIS’ own commentary sums it up quite eloquently:

“In the half-decade since the peak of the crisis, the hope was that significant progress would be made in the necessary deleveraging process, thereby enabling a self-sustaining recovery. Instead, the debt of households, non-financial corporations and government increased as a share of GDP in most large advanced and emerging market economies from 2007 to 2012. For the countries in [chart 2] taken together, this debt has risen by $33 trillion, or by about 20 percentage points of GDP. And over the same period, some countries, including a number of emerging market economies, have seen their total debt ratios rise even faster. Clearly, this is unsustainable. Overindebtedness is one of the major barriers on the path to growth after a financial crisis. Borrowing more year after year is not the cure.”

Reality is perhaps a wee bit more complicated than BIS makes it out to be for the simple reason that you cannot have all sectors of the economy de-lever at the same time without negative implications for economic growth. Let’s make the assumption that exports and imports are constant[2]. Under that assumption, if both the public (G) and private (I + G) sectors were to de-lever simultaneously, GDP would be badly affected, as GDP = C + I + G; a simple accounting identity which is often ignored in the debate.

Following this logic, if BIS’ advice were followed word for word, it would engineer a depression. Having said that, BIS is right to warn about the current path because sooner or later the bond market will puke, unless we change the path we are on.

What if?

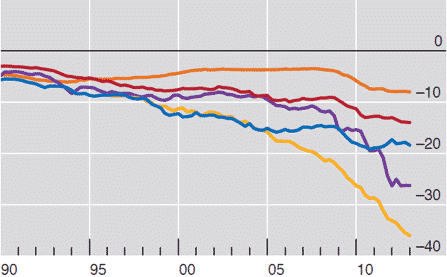

Now, let’s change gear and look at the effect of a rise in interest rates. BIS did precisely that in its recently published annual report. A 300 bps rise in bond yields across the term structure would, according to their calculations, do substantial damage to financial institutions’ balance sheets. Holders of U.S. Treasuries alone would lose in excess of $1 trillion on such a move in rates, equal to 8% of U.S. GDP. Other countries would fare even worse. Losses on JGBs would equal 35% of the Japanese GDP, effectively wiping out its banking industry in the process. Holders of U.K. bonds wouldn’t do much better, losing the equivalent of 25% of U.K. GDP (chart 3).

So what is the probability of such a significant increase in bond yields across the term structure? Well, yields are not likely to jump 300 bps overnight, but recent events have demonstrated that bond yields can rise surprisingly quickly, just as they did in 1994 when bond investors were last seriously wrong-footed. Only eight weeks ago, in early May, the U.S. 10-year bond yielded 1.63%. 7 weeks later, towards the end of June, it had risen to 2.66%. Not many saw that coming.

Chart 3: Change in value of government debt after rise in yields (% of GDP)

Source: Bank for International Settlements, 83rd Annual Report, 2012-13

Note: Assumes 300 bps rise in yields across term structure.

This leads to the first important observation of the day. Central banks will almost certainly use any conceivable tool at their disposal to keep interest rates low for the simple reason that nobody can afford for rates to rise. Governments cannot. Financial institutions can’t either as their balance sheets are loaded with carry trades, designed to repair their fragile balance sheets. Households certainly can’t as higher rates would mean higher mortgage costs for a sector that is already financially stretched.

The only industry which could meaningfully benefit from a rise in interest rates would be the pension fund industry, as higher rates would translate into a lower funding deficit for all those underfunded pension schemes around the world with defined benefits. I suppose every cloud has a silver lining, but what’s the value of a fully funded pensions industry if our banking system has been bankrupted in the process? (Cynics would argue that most banks are already bankrupt if only they would come clean on the quality of their loan books, but that’s a discussion for another day.)

The short answer is thus that few countries can afford for interest rates to increase, even if it creates an even bigger problem further down the road for all those underfunded pension schemes. Mark Carney, the new governor of the Bank of England will, if necessary, have to pull out all the stops to keep rates in check.

Stock versus flows

Now, the big question: Can central banks actually control interest rates? Ben Bernanke had the following to say on that topic in his now famous helicopter paper, presented to the National Economists Club in November 2002:

“There are at least two ways of bringing down longer-term rates, which are complementary and could be employed separately or in combination. One approach, similar to an action taken in the past couple of years by the Bank of Japan, would be for the Fed to commit to holding the overnight rate at zero for some specified period. Because long-term interest rates represent averages of current and expected future short-term rates, plus a term premium, a commitment to keep short-term rates at zero for some time–if it were credible–would induce a decline in longer term rates.

A more direct method, which I personally prefer, would be for the Fed to begin announcing explicit ceilings for yields on longer-maturity Treasury debt (say, bonds maturing within the next two years). The Fed could enforce these interest-rate ceilings by committing to make unlimited purchases of securities up to two years from maturity at prices consistent with the targeted yields.”

As we all know now, Bernanke has had plenty of opportunities to test his ideas since he gave his helicopter speech back in 2002, and the dramatic compression of yields since then seems to support the general notion that yields can indeed be controlled by central banks. There is only one (major) weakness associated with that view and that is what can best be described as the flow versus stock argument.

The flow argument, which compares supply and demand, is often used as an argument for continued low interest rates. Barclays estimated in a recent research report that the projected $2 trillion supply of new AA and AAA-rated debt in 2013 will be dwarfed by the $2.5 trillion of projected central bank purchases of high grade paper (chart 4).

Chart 4: Supply and demand for fixed income assets (AA and higher)

Source: “Central banks sweep the board” Barclays Research, 26 April 2013

The problem with this argument is that it ignores the outstanding stock of debt already in circulation (the stock argument). There are approximately $209 trillion of financial assets floating around the world today, $45 trillion of which are accounted for in government bonds, $65 trillion in loans, and $46 trillion in corporate debt[3]. Meanwhile, central bank balance sheets have doubled in size from about $10 trillion in 2007 to approx. $20 trillion today[4]. Even after years of loading up on bonds, central banks still account for only a modest share of the total stock of debt. If other holders of debt collectively decided that a higher risk premium would be warranted, central banks could do little to stop that from happening.

So when Bernanke says, as he did in 2002, that central banks could (and subsequently would) commit themselves to unlimited purchases, he is making a calculated bet that, by making such a statement, he can control investor sentiment. He is effectively playing mind games with investors which brings me to the next point.

Bernanke’s master plan

Why did Bernanke say what he did in his speech on 22 May and why did bond markets react so violently? As far as Bernanke’s motives are concerned, I think it is relatively straight forward. The Fed is growing increasingly concerned (or so I believe) about the unintended consequences of QE, that they are creating yet more asset bubbles that will blow up at some stage and they chose to inject a little bit of uncertainty into the markets in order to see how much froth there actually was. As we know now, there was plenty. David Zervos of Jefferies phrased it quite elegantly:

“Yesterday’s pronouncements appear to be a conscious effort to inject uncertainty into a fixed income market that feeds on certainty. He was taking a cue from the great Hyman Minsky. By acting against a market that had become too complacent, he was attempting to force out the dangerous and excessive leverage in the system. And while that may feel a little painful right now, we may end up being very thankful that the Committee took the actions it did Wednesday in the name of preserving future financial stability.”

Marc Faber, when asked on Bloomberg TV if Bernanke actually meant what he said on tapering, offered the following explanation:

“If you say that if he means what he says, then you believe in Father Christmas. He said if the economy does not meet the expectations of the Fed in one year’s time, they will consider additional measures. In other words, if the economy has not fully recovered by mid-2014, more QE will be forthcoming. As I said already three years ago, we are going to go with the Fed to QE99.”

If you look carefully at what Bernanke actually said, both in his statement and in the subsequent Q&A, and if you add to that the naked facts about the U.S. economy, the only conclusion you can rationally arrive at is that the probability of any tapering this year is in fact quite low and the chance of a rate hike is 0.0000000%. It was much ado about nothing. So why did markets react as violently as they did? I can think of two reasons.

Firstly, patience is a virtue that is at risk of getting lost, perhaps forever. The internet has been good for many things, but I suspect it has done tremendous damage to our capacity for absorbing complex information. If we can’t be presented with the information in headline form in a matter of seconds, we simply move on. Many of us no longer have the patience for details. Put slightly differently, investors didn’t listen carefully enough to what Bernanke said. They took the headlines from Bloomberg and other news agencies and acted accordingly.

I have learned subsequently that central bankers here in Europe, who understood the context in which Bernanke’s speech was framed, were astonished by the severity of the reaction. They thought, as I do, that it was much ado about nothing. This also ties in with the recent frantic activity from various central banks, aiming to calm markets by reassuring that interest rate hikes are years away.

Secondly, I believe Zervos is correct in suggesting that complacency had found its way back into the markets. As mentioned earlier, the 10-year T-bond had reached an unprecedented 1.63%, and high yield bonds were trading at a mind-blowing 4.8%. Equities hadn’t seen a correction for many months. Investors were getting cocky and Bernanke chose to teach us a lesson.

Long term implications

So what are the longer term consequences of all of this? There are in fact several.

Interest rates will stay low for a long time – long as in years, not months. This statement requires some qualification. As referred to earlier, I am not entirely convinced that central banks actually control the long end of the yield curve; however, they do control policy rates and, by implication, the near end of the yield curve. This implies that the spread between 2-year notes and 10-year bonds is very unlikely to narrow and quite likely to widen over time.

In the UK there is a risk that a weakening currency may lead to some modest increase in inflation but, generally speaking, inflation is not a problem, and all those who predicted runaway inflation as a result of QE will be thoroughly disappointed. Longer term, deflation is a much bigger risk. Hence, if (when) interest rates eventually begin to rise it will be as a result of growing default risk, not rising inflation.

Equities may actually perform better than one would expect from a fundamental point of view, even if it will be a far cry from the raging bull market of 1982-2000. My cautious optimism is partly due to the ample supply of liquidity and partly because low interest rates will drive the flow of funds towards equities.

Currencies are likely to be volatile, perhaps violently so. The accounting identity referred to earlier (GDP = C + I + G which should actually read GDP = C + I + G + (X-M)[5]) will drive governments all over the world to pursue a weaker currency in the belief that growing exports are the solution to their problem. The problem is that global trade is a zero sum game. Not everyone can be a net exporter. Hence the likely winners in a currency war are those countries not tied to a currency union whether explicit (EU) or implicit (US). Amongst the larger countries in the world, Japan and the U.K. both look well positioned to be able to manage their currency down from current levels.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, in an environment of continued QE, asset prices are likely to replace inventory cycles as the principal cause of recessions. This has important implications for monetary policy and Bernanke’s recent speech should be interpreted in this light. It is important that new policy tools are introduced to manage this risk. Expect to hear from us again in early September. In the meantime, enjoy the sunshine.

Niels C. Jensen

8 July 2013

©Absolute Return Partners LLP 2013. Registered in England No. OC303480. Authorised and Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered Office: 16 Water Lane, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 1TJ, UK.

Important Notice

This material has been prepared by Absolute Return Partners LLP (ARP). ARP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom. It is provided for information purposes, is intended for your use only and does not constitute an invitation or offer to subscribe for or purchase any of the products or services mentioned. The information provided is not intended to provide a sufficient basis on which to make an investment decision. Information and opinions presented in this material have been obtained or derived from sources believed by ARP to be reliable, but ARP makes no representation as to their accuracy or completeness. ARP accepts no liability for any loss arising from the use of this material. The results referred to in this document are not a guide to the future performance of ARP. The value of investments can go down as well as up and the implementation of the approach described does not guarantee positive performance. Any reference to potential asset allocation and potential returns do not represent and should not be interpreted as projections.

Absolute Return Partners

Absolute Return Partners LLP is a London based client-driven, alternative investment boutique. We provide independent asset management and investment advisory services globally to institutional investors.

We are a company with a simple mission – delivering superior risk-adjusted returns to our clients. We believe that we can achieve this through a disciplined risk management approach and an investment process based on our open architecture platform.

Our focus is strictly on absolute returns. We use a diversified range of both traditional and alternative asset classes when creating portfolios for our clients.

We have eliminated all conflicts of interest with our transparent business model and we offer flexible solutions, tailored to match specific needs.

We are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the UK.

Visit www.arpinvestments.comto learn more about us.

Absolute Return Letter contributors:

Niels C. Jensen

Nick Rees

Tricia Ward

[1] Source: Woody Brock, Strategic Economic Decisions.

[2] It is fair to assume little or no impact from external trade in the short to medium term, as both exports and imports move at a glacial pace.

[3] Source: GaveKal Research via Barrons.

[4] BIS, 2012-13 annual report.

[5] X stands for exports and M for imports, so X-M equals net exports.

Comments are closed.